PDF version: Notes on Fundraising Mechanics for Startups by Logan Thrasher Collins

Valuation

A company’s valuation is initially an estimate of how much the company is worth as set by methods such as the following.

- Comparable transactions: looking at valuations of startups at a similar stage in the given sector.

- Berkus method: assigning dollar values to qualitative factors such as idea, team, prototype, sales, etc. and adding them up to obtain the valuation of the company.

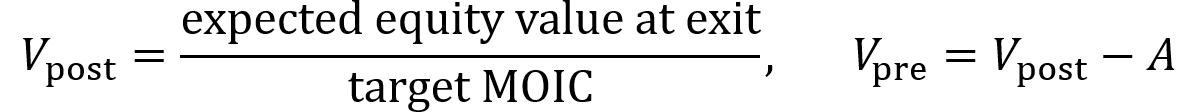

- VC method: estimate the exit value of the company (value when it is sold) and divide by the firm’s desired multiple on invested capital or MOIC (e.g. 10×) to obtain the post-money valuation Vpost. Then subtract the amount invested to obtain the pre-money valuation Vpre.

Pre-money valuation is the company’s agreed-upon value before new capital is invested. It sets the price at which new shares can be sold and thus dictates how much of the company the founder gives up for the round. Post-money valuation is the pre-money valuation plus the newly invested amount of funds. It dilutes everyone’s percent ownership immediately after the round.

Dilution refers to the decrease in the percentage of the company owned by the founders. So, one might say “the round diluted us by 20%” or “we sold 20% of the company” or “the founders are at 80% ownership post-money”.

- When raising an amount A of funds at a pre-money valuation of Vpre, the post-money valuation Vpost of the company equals Vpre + A.

- The proportion owned by the investor Pinvestor after the round is A divided by Vpost. Multiply by 100 to obtain percentage.

- The proportion owned by the founder Pfounder after the round is 1 – Pinvestor. Multiply by 100 to obtain percentage.

Though it can vary widely, a common dilution percentage to aim for is 20%. This allows for raising at a solid valuation while mitigating the risk of not hitting the fundraising target for the next round (and facing a “down-round”).

Pricing the company for the next round

For a subsequent round of fundraising, the post-money valuation of its preceding round is used as a reference point for starting to evaluate the new pre-money valuation. However, it is usually not the final number. If the new pre-money valuation is higher, the round is referred to as an “up-round”. If the new pre-money valuation is the same, the round is referred to as a “flat round”. If the new pre-money valuation is lower, the round is referred to as an “down-round”.

Several factors can influence the new round’s pre-money valuation.

- If a company hits its milestones (e.g. revenue, new data, patents, hires), this can justify a markup where the investors pay more for less dilution of the founder’s ownership.

- If a company does not hit its milestones or grow, a flat round or down-round may be the only option to move forward.

- Market conditions for a given industry can fluctuate and push the company’s price (pre-money valuation) up or down.

- Other factors such as SAFEs, convertible notes, and option pool top-up can influence the company’s price.

Shares

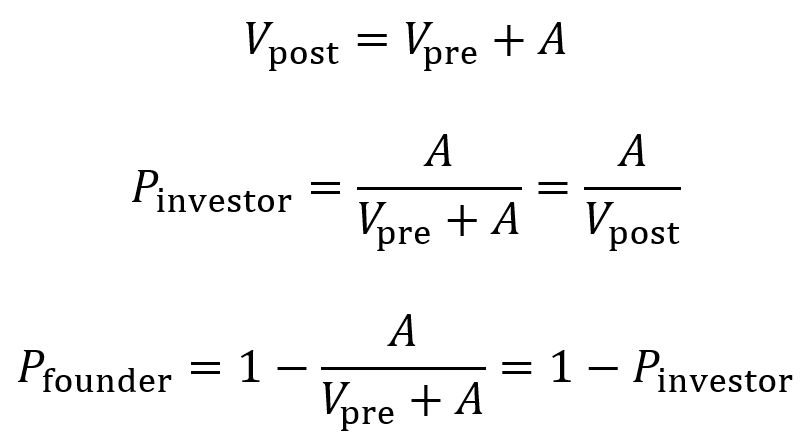

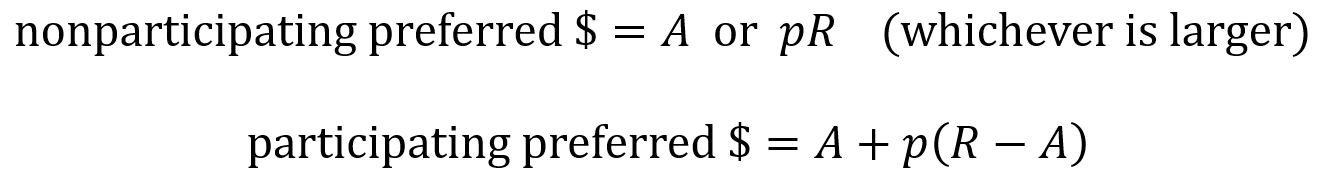

When a company raises a priced equity round, the board and stockholders authorize the creation of shares and sell them to the investor (an issuance) if there are not enough unissued shares available. Price per share is calculated by dividing valuation V by the company’s number of shares. When new shares are issued in a round, the number of new shares is the amount A raised divided by the price per share.

Higher valuations lead to higher price per share and fewer shares issued for the same amount of investment, which means less dilution. Larger round sizes with more cash lead to more shares issued at the same price, which means more dilution.

Stock

Shares may exist as units of common stock or preferred stock. A company’s common stock is typically held by founders and employees. Unlike preferred stock, it does not come with special contractual protections. Those who hold common stock have standard voting rights for decisions like board elections, mergers, etc.

Preferred stock (usually a type called convertible preferred) is a type of equity that is typically held by investors. It comes with a number of protections for investors including liquidation preference (discussed in the next paragraph), having a separate preferred vote on major company actions, anti-dilution protections, pro rata rights (discussed in the next section), and sometimes board seats or rights to observe board meetings.

Liquidation preference describes the multiple by which the investor receives their original investment back after a liquidation event (e.g. acquisition/merger, asset sale, winddown). Term sheets define what counts as a liquidation event. The multiple is usually 1×, but higher multiples exist (1.5×, 2×, etc.) and are not as founder-friendly.

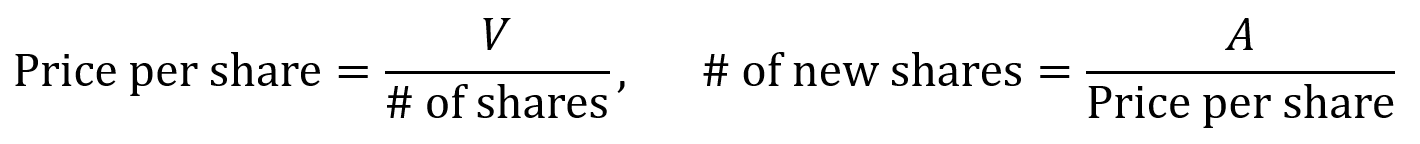

Preferred stock can be categorized as non-participating or as participating. When a liquidation event happens for a non-participating preferred stock, the investors receive their money back as either the “preference” or the “as-converted common”. The preference is the original amount they invested multiplied by the liquidation preference factor. The as-converted is the amount of money generated from the liquidation event times the percentage of the company owned by that investor.

- For example, consider a $12M acquisition of a company where the investor originally invested $5M at a $15M pre-money valuation ($20M post-money valuation). The investor owns 25% of the company based on these numbers.

- So, the investor can take 25% of $12M (which is $3M) or can take their original $5M back. Because $5M is higher, they receive $5M.

- But for an example with an acquisition of $200M, the investor would take higher value of 25% of the $200M (which is $50M) rather than the original $5M.

When a liquidation event happens for a participating preferred stock, the investor first takes the preference amount (their original investment) and then takes additional funds pro rata, which here means they take an amount equal to the remaining money from the liquidation event times their percentage ownership. (Pro rata rights are discussed more in the next section).

- Consider again the example of a $12M acquisition of a company where the investor originally invested $5M at a $15M pre-money valuation ($20M post-money valuation) and thus owns 25%.

- The investor first takes $5M, then additionally takes 25% of the remaining $12M – $5M = $7M, where 25% of $7M = $1.75M.

- So, the investor takes a total of $5M + $1.75M = $6.75M.

The effects of non-participating preferred and of participating preferred are summarized by the following equations where R is the amount of money from the liquidation event (the return), A is the original amount invested and p is the percentage of the company owned by the investor (as a proportion).

Pro rata rights

Pro rata rights are a legal stipulation that gives existing investors the right (but no obligation) to buy enough shares in a future financing round to retain the same ownership percentage as their initial investment. For example, if an investor owns 20% in the seed round and has pro rata rights, then they have the right to purchase 20% of new shares issued during the series A round so that they keep the same percentage ownership. (With the board’s authorization, the corporation issues new shares so that additional investment can be taken on).

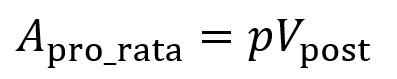

Consider an existing investor with pro rata rights and owns p% of the company before the new round. The company raises an amount of A dollars at an agreed upon post-money valuation of Vpost. For the existing investor to keep ownership of the p% of the company, they must invest an amount Apro_rata (where p is the percentage converted to a fraction).

The amount Apro_rata comes in addition to the amount invested by the new lead investor, so at least one of three items must be adjusted.

- The round size must grow (this is most common).

- The new lead investor’s ownership must shrink (this is rarer).

- The valuation must increase so the lead investor still obtains their target percentage ownership.

As an example, consider a series A round (note: do not confuse “series A” with the variable A chosen to represent amount of funds invested) raised after a seed round where the seed investor was given pro rata rights.

- In this example, let the target series A post-money valuation be $30M and new the lead investor’s target ownership be 20%.

- Without the seed investor having pro rata rights, the lead investor would be able to invest $6M (adding to a $24M pre-money valuation) and own 20% of the company. If the seed investor’s stake is worth $4.8M (owning 20% of $24M beforehand), then the seed investor’s ownership will be diluted to 16% due to the lead investor having bought more of the company.

- With the seed investor having pro rata, they will have the right to invest another $1.2M (buy $1.2M worth of shares) when the target post-money valuation stays at $30M, keeping them at 20% since they previously held a stake value of $4.8M (20% of $24M) and they now hold a stake value of $4.8M + $1.2M = $6M (20% of $30M).

- With the seed investor having pro rata rights, the new lead investor will only be able to invest $4.8M (16% of $30M) assuming the post-money valuation must stay at $30M.

- With the seed investor having pro rata rights, the lead still could invest $6M and retain 20% ownership if the post-money valuation rises to $36M or the total round amount grows to $7.2M.

Employee stock ownership plan (ESOP)

An ESOP is a collection of a company’s shares that it reserves (but has not yet issued) for giving to current and future employees and advisors. It facilitates talent attraction and retention and aligns employee incentives with the company’s incentives. On cap tables, ESOP appears despite the shares not having been issued (it is labeled as “non-issued options”) and is counted when calculating ownership percentages. At the seed and series A stages, ESOPs typically occupy around 10%-15% of the cap table. Note that ESOPs are taken out of the founder’s shares and not the investor’s shares.

VCs generally require the ESOP pool to be included or “topped up” within the pre-money valuation so that dilution from the ESOP does not dilute them but instead affects the founders and earlier stakeholders.

To calculate the size of the option pool and how it affects the new investor’s shares, first find the post-money valuation Vpost from the amount invested A and the investor’s target ownership percentage.

- For example, if the investor provides $6M and has a target ownership percentage of 20%, then the Vpost = $6M/0.2 = $30M.

- Let x equal the number of option pool shares necessary to reach 10% at post-money valuation. Let y equal the new shares that the investor will purchase with the $6M. In this example, the number of pre-round shares will be 10M without the ESOP top-up.

- Ownership percentages are measured after the round closes. Solving the algebraic system of equations below gives x = 1.4286M shares and y = 2.8571M shares.

- Pre-round share count after ESOP top-up is 10M + 1.4286M = 11.4286M.

- Number of total post-round shares is 10M + 1.4286M + 2.8571M = 14.2857M.

- Price per share is $30M/14.2857M = $2.10.

- Pre-money valuation is therefore 11.4286M×$2.10 = $24M.

- The ESOP pool top-up decreases the founder’s effective pre-money valuation since the price per share falls from $24M/10M = $2.40 to $24M/11.4286M = $2.10. That is, since the founder still holds 10M shares, the founder’s stake is 10M×$2.10 = $21M (rather than $24M).

Convertible notes

A convertible note acts as a short-term loan investors make to a startup. It is similar to debt in that it has a principal amount, interest rate, and maturity date. However, the expectation is that the note will convert into preferred equity when a later priced round is raised (e.g. a series A). Since valuation is set later, the negotiations move faster and legal fees for convertible notes remain lower.

Convertible notes come with a discount on shares for early-stage investors. (Often around 15%-25% off of the share price paid by series A investors). This rewards early investors who take a risk on the company.

Convertible notes come with a valuation cap which sets the maximum price per share once conversion to equity occurs. (For pre-clinical companies, often around $8M-20M for pre-money caps). This protects early investors if the series A price per share is high.

Convertible notes come with interest (often around 4%-8% simple interest accruing to principal) which also converts into equity upon raising a priced round. This further rewards early investors.

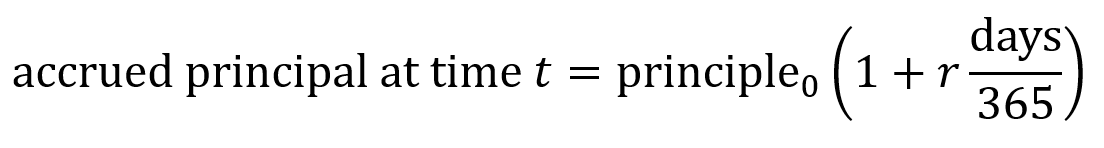

The accrued principal is the total amount that needs to be “paid back for the loan” (though in this case it will be paid back in equity) which consists of the principal (base loan amount of money) plus the accrued interest. Seed-stage biotech convertible notes usually use simple interest rather than compounding interest. Simple interest is calculated linearly using the equation below where r is the interest rate as a proportion (e.g. 6% interest = 0.06 = r). Number of days is counted from the issue date until the conversion trigger or the maturity date.

Convertible notes come with a maturity date (often around 18-36 months). If no priced round occurs by the maturity date, investors may (i) force conversion of their shares into common stock, (ii) extend the maturity date, or (iii) require repayment. Maturity dates should thus be chosen to give ample room to complete one’s next milestone.

The early investors purchase shares at a conversion price which is the lower of either the discounted series A price or the price implied by the cap.

- As an example, consider a situation where one raises $1M on a convertible note with 6% interest, a 20% discount, and a $12M cap. In this example, let us say that there are 4M pre-money shares.

- Eighteen months later, a series A of $20M in new capital is raised at $4.00 per share.

- With the interest, the accrued principal amount is $1M(1 + 0.06×1.5 years) = $1.09M.

- The discounted price per share is $4.00×(1 – 0.20) = $3.20

- The capped price per share is $12M/(4M shares) = $3.00

- So, the note converts at $3.00 per share price since that is the lower value between the discounted price and the capped price.

- $1.09M/$3.00 = 363,333 new preferred stock shares issued to the note holder (the investors).

It is important to realize that the stockholders approve the board’s creation of new shares to pay back the convertible note. Everyone’s ownership percentage adjusts accordingly.

SAFEs

A SAFE or Simple Agreement for Future Equity is similar to a convertible note in that the investor gives a startup funding in exchange for the right to receive equity later. Unlike convertible notes, SAFEs do not accrue interest nor do they have a maturity date.

Conversion is triggered when the company raises a priced round (typically a series A). Conversion can also happen when a liquidity event occurs (e.g. acquisition or IPO). The amount of money provided by the SAFE then converts into equity, at which point the investor receives shares as determined by the valuation and number of shares issued. Investors only own shares once the conversion happens.

As protections for investors, SAFEs can (but do not always) include valuation cap, discount, and/or most favored nation (MFN) clause.

Valuation cap is the maximum post-money valuation at which the SAFE converts into equity. Even if the valuation of the company is later set at higher, the SAFE converts at the valuation set by the cap, leading to the investor receiving shares as if the cap were the valuation.

- For example, consider a scenario where the SAFE investment is $100K, the cap is $4M the company raises a $5M series A round at a $10M pre-money valuation, and shares are priced at $1.00/share.

- There are 10M shares initially from the $10M/($1.00/share). The series A investor adds $5M/($1.00/share) = 5M more shares. Still more shares (see below to find the exact number) are then added due to the SAFE.

- The amount of shares from the SAFE can be calculated by first determining the SAFE holder’s percentage ownership. Divide their investment amount A by the post-money cap Cpost, so A/Cpost = 100K/4M = 2.5% ownership.

- Next take the 2.5% ownership of the SAFE investor and divide by the total remaining percentage ownership (100% – 2.5% = 97.5%) and multiply by the initial number of shares (10M here), so 10M(2.5%/97.5%) = 256,410 shares.

- 10M (founders) + 5M (series A investor) + 256,410 (SAFE investor) = 15,256,410 shares total.

- In the end, the founders own 10M/15,256,410 = ~65.6%, the series A investor owns 5M/15,256,410 = ~32.8%, and the SAFE investor owns 100K/15,256,410 = ~1.68%.

- Note that if there was no cap, the SAFE investor would receive $100K/($1.00/share) = 100K shares instead. This would correspond to $100K/($15M + $100K) = 0.66% ownership by the SAFE investor after the series A round (which is much less than with the cap).

As an interesting side note, valuation cap used to correspond to pre-money valuation, but this was changed by Y Combinator to post-money valuation in 2018. Now almost all SAFEs use post-money valuation for their calculations.

Discount means the investor receives a percentage discount (often ~10%-20%) on the share price in the round when the SAFE converts to equity. Note that this only occurs in the conversion round and does not persist into future rounds beyond that.

- As an example, consider a scenario where the series A investor pays $1.00 per share and the SAFE has a 20% discount.

- The SAFE then converts at $0.80 per share and the SAFE holder receives more shares for the same amount of money compared to the new series A investors.

Finally, an MFN clause gives the SAFE holder investors to adopt better terms if the company issues SAFEs later which have more favorable provisions. The original SAFE holder investors can then receive the more favorable provisions found in the terms of the new SAFEs.