Author: logancollins

Notes on Nucleic Acid Bioconjugation

Credit for Images: Bioconjugate Techniques (Greg T. Hermanson)

Applications and Challenges of DNA Bioconjugates

- Modified oligonucleotides are used in a variety of techniques that involve hybridization.

- Sensitive hybridization reagents can use oligonucleotides that are labeled with a fluorescent marker or an enzyme that produces observable products.

- DNA does not include many of the easily modified functional groups present in proteins.

- To modify DNA, other functional groups usually must be attached first.

- The two main categories of DNA bioconjugation techniques are chemical and enzymatic. Some enzymatic approaches are described here.

Random-Primed Labeling

- Random-primed labeling is a form of enzymatic DNA bioconjugation that uses a reaction process with just a single denaturation step, a single annealing step, and a single extension step.

- The following materials are added to a mixture for random-primed labeling.

- Random hexa-deoxynucleotides to serve as primers.

- dNTPs (ordinary nucleotides).

- Modified dNTPs such as 32P radiolabeled nucleotides (which do not affect the probe’s hybridization efficiency), fluorescent dye labeled nucleotides, or affinity molecule labeled nucleotides (which bind observable compounds).

- Template DNA.

- The Klenow fragment version of DNA polymerase I that lacks 5’-3’ exonuclease activity.

- The ratio of ordinary dNTPs to modified dNTPs decides the magnitude of labeling by determining the amount of modified dNTPs that are incorporated.

- Random-primed labeling produces a random array of oligonucleotides of different lengths and sequences corresponding to different parts of the template.

- This is because the oligonucleotides are generated by the replicated sequences between annealed random hexa-deoxynucleotide primers (the oligonucleotides also include the primer sequence at their 5’ ends).

Nick Translation Labeling

- Nick translation labeling is a form of enzymatic DNA bioconjugation that uses a 15°C incubation temperature for the reaction.

- The following materials are added to a mixture for random-primed labeling.

- dNTPs (ordinary nucleotides).

- Modified dNTPs such as affinity tagged nucleotides or fluorescently tagged nucleotides.

- Template DNA.

- Mg2+ and low concentrations of pancreatic DNase I (which only has single-stranded endonuclease activity in the presence of Mg2+).

- DNA polymerase I.

- The small amount of DNase I with Mg2+ makes a few single-stranded nicks in the template, allowing the DNA polymerase I to begin nick translation. In this way, new dNTPs and labeled dNTPs replace the nucleotides in the original template molecule.

- The ratio of ordinary dNTPs to modified dNTPs decides the magnitude of labeling by determining the amount of modified dNTPs that are incorporated.

PCR Labeling

- PCR labeling is a form of enzymatic DNA bioconjugation that uses a PCR reaction.

- The standard PCR components are added to the reaction. In addition, some labeled dNTPs or primers containing labeled nucleotides are also added.

- When labeled dNTPs are added, the ratio of ordinary dNTPs to modified dNTPs decides the magnitude of labeling by determining the amount of modified dNTPs that are incorporated.

- RT-PCR versions of PCR labeling can be used to create sensitive assays for RNA viruses.

Terminal Transferase Labeling

- Terminal transferase labeling uses terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) to add a labeled dNTP to the 3’ ends of DNA oligonucleotides without the need for a template.

- TdT (found in certain lymphocytes) usually adds multiple non-templated nucleotides to the 3’ ends of oligonucleotide strands.

- In the presence of Co2+ salts, TdT only adds single non-templated nucleotides to the 3’ ends.

- By applying TdT to add a labeled dNTP to the 3’ ends of oligonucleotides, the middle of the oligonucleotide strand will not have its hybridization efficiency disturbed. This is especially useful for large labels like biotin-streptavidin detection conjugates or many fluorescent dyes.

T4 RNA Ligase 1 Labeling

- T4 RNA ligase 1 labeling uses a very similar mechanism to that of TdT labeling. T4 RNA ligase 1 adds a single nucleotide to the end of an RNA oligonucleotide.

- This also has the benefit of not affecting hybridization efficiency.

- Unlike the other methods, T4 RNA ligase 1 labeling requires labeled bis-phosphoryl nucleotide derivatives (which have one phosphate on the 5’ end end one phosphate on the 3’ end) rather than labeled dNTPs.

Individual Labeled Nucleotides

- Although many modifications can be made to individual nucleotides, most block the activity of enzymes used for labeling of oligonucleotides. However, some will allow the activity of one or more type of labeling enzyme (see diagram).

- Sometimes, it can be beneficial to add an amine to a nucleotide so that the amine can react with other chosen molecules to form various types of conjugates.

- There are numerous chemical techniques for labeling individual nucleotides.

Rational Romanticism

Many rationalists dismiss emotion as lacking intrinsic and practical value. Many romantics dismiss science as lacking emotional and spiritual value. Most people assume that emotion and rationality are mutually exclusive. Unfortunately, these attitudes have caused a schism between the cultures of imagination and science. I propose that unifying rationality and romanticism will open the floodgates to a beautiful future.

Some behaviors which are considered as illogical by the pure rationalist actually do have logical consistency when approached from the perspective of rational romanticism. I would argue that major risks are worthwhile even if there is insufficient data to predict the “degree of risk.” For instance, ambitious research projects are less likely to succeed than more moderate ones and it is difficult to gain a reasonable measure for the degree of risk involved in such projects. Some researchers might deem ambitious projects as having too much unknown risk to pursue. But throughout history, we have seen that the people who ignore boundaries and even apparent impossibilities, the people who keep obsessively fighting to make their vision a reality no matter the odds, we have seen that these are the people who change the world. The space program was once considered ludicrous as was heavier-than-air flight. Experts and laypeople alike have scoffed at inventions such as the lightbulb, the automobile, and the home computer.

By contrast, the activities of scientists have often befuddled and frightened more artistically inclined peoples. In stories, science and technology usually appears as a tool of the villains. Consider Frankenstein, Gattaca, Brave New World, Jurassic Park, The Terminator, and countless other fearmongering works of fiction. (It should be noted that Frankenstein may or may not have originally been intended this way, but that it is almost always interpreted in an anti-science manner by the public). The stereotype of the mad scientist frames science as at best irresponsible and arrogant and at worst evil. The poetry magazine Carbon Culture features poems that are centered almost exclusively on attacking technology. Transhumanists are nearly universally vilified or dismissed as crazy by the media. Religious and environmental “bioethicists” like Fukayama, Kass, and McKibben viciously denounce science as immoral. We are living in an age when the activities of emotionally-minded individuals hold science back rather than driving it forward. Emotion is powerful and intrinsically valuable, but it should be used for constructive and not destructive purposes.

If we cultivate rational romanticism, we can achieve wonders. The cultures of imagination and science are currently opposed. But by bringing them together, science will not be limited by status quo bias or stifling pragmatism. Likewise, art will not be limited by an aversion to the beauty found in science and technology. In this scenario, science and art will be synonymous. Emotional intensity will be channeled towards solving challenges and enriching the human experience. With the combined power of science and emotion, we can make dreams into reality.

Notes on: Universal resilience patterns in complex networks, Gao et al. 2016

Resiliency Overview

- Resiliency is a system’s ability to maintain its overall structure and function when disturbances act upon its network.

- Some examples include environmental systems, technological systems, and biological systems that are subject to environmental changes, errors, or failures. More resilient systems will be stable despite such perturbations.

- Loss of resiliency occurs when some bifurcation converts a stable fixed point into an unstable fixed point. Bifurcations occur when a changing parameter results in one or more fixed points undergoing stability transitions.

- Below is the equation of a 1D dynamical system (a flow on the line) with an adjustable parameter β.

Improved Model of Resiliency

- Gao et al. developed a higher-dimensional mathematical model to allow for better prediction of network resilience than past models.

- The main equation of this model is given below. Aij represents a weighted adjacency matrix, N is the number of nodes in the network, and x = (x1,…,xN)T is a vector representing the activities at each node. The function F(xi) describes the activity of each given node xi independent of the influences of other nodes. The function G(xi,xj) is a rule describing the influence of node xj on node xi.

- Disturbances to networks described by this equation might include gaining nodes or edges, losing nodes or edges, changes in edge weights, or changes in the values of parameters that are part of the functions F and G.

Resiliency Model Applied to Ecological Networks

- Below, this resiliency model describes abundance of species. The function xi(t) is the abundance of a species i. The parameter Bi represents the incoming migration rate of each species. The second term considers logistic growth with carrying capacities Ki as well as the Allee effect. According to the Allee effect, small populations, where xi<Ci will decline (negative growth). Finally, the third term describes mutualistic interactions between species xi and xj (i.e. plant-pollinator relationships). At high abundances of xi and xj, this term tends to plateau. The weighted adjacency matrix Aij represents the strengths of these mutualistic interactions. Di, Ei, and Hj are further adjustable parameters.

- The authors tested the resiliency of experimentally mapped ecological networks using this model. First, a fraction fn of the plant nodes was removed, simulating plant extinctions. Then, a fraction fI of the pollinator nodes was removed, simulating pollinator extinctions. Finally, the weights of the matrix Aij were randomly rescaled such that the average weight decreased to a fraction fw of the original average weight.

- Initially, the ecological networks each only possessed a single stable fixed point, xH. These fixed points described high average abundances among the species. Upon applying perturbations, the networks maintained stability until thresholds were reached. Each threshold was dependent on its network and the type of perturbation applied (plant node removal, pollinator node removal, or changes to edge weights). After passing the thresholds, each network gained an additional stable fixed point, xL. These fixed points described low average abundances among the species (an undesirable state).

- For example, network1 lost resilience after 35% of its pollinators were removed, while Network5 lost resilience only after 80% of its pollinators were removed.

Resiliency Model Applied to Gene Regulatory Networks

- Below, the resiliency model describes the activity of genes in coli and S. cerevisiae using Michaelis-Menten kinetics. The function xi(t) is the activity of a gene i. The first term represents the degradation rate (f=1) of a protein (from gene i). Alternatively, if the xi in the first term is squared (f=2), this term can represent dimerization. The second term describes gene expression levels, where the Hill coefficient h represents the level of cooperativity in the regulation of gene i by protein j. The weighted adjacency matrix Aij represents regulatory connections among the genes.

- By computing the average activity of all genes in a cell, the resiliency model provided a method of predicting cell viability. If a cell’s , then the model predicts that the cell will die. If a cell’s , then the model predicts that the cell will be viable.

- Once again, depending on the gene regulatory network and the types of perturbations, resilience loss occurred after thresholds (each specific to the network and the perturbation types) were crossed. The types of perturbations for this application included gene deletions, changes to the weights of regulatory interactions, and global environmental changes.

My Digital Art Sampling

Self-Replicating Cursors

Transcendent Entomologies

Transcendent Entomologies

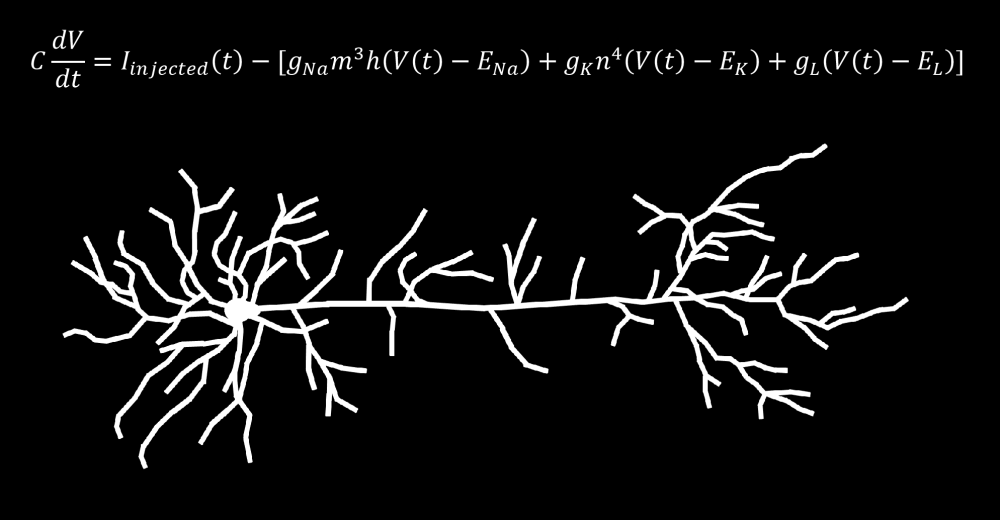

Hodgkin-Huxley Neuron

Hodgkin-Huxley Neuron

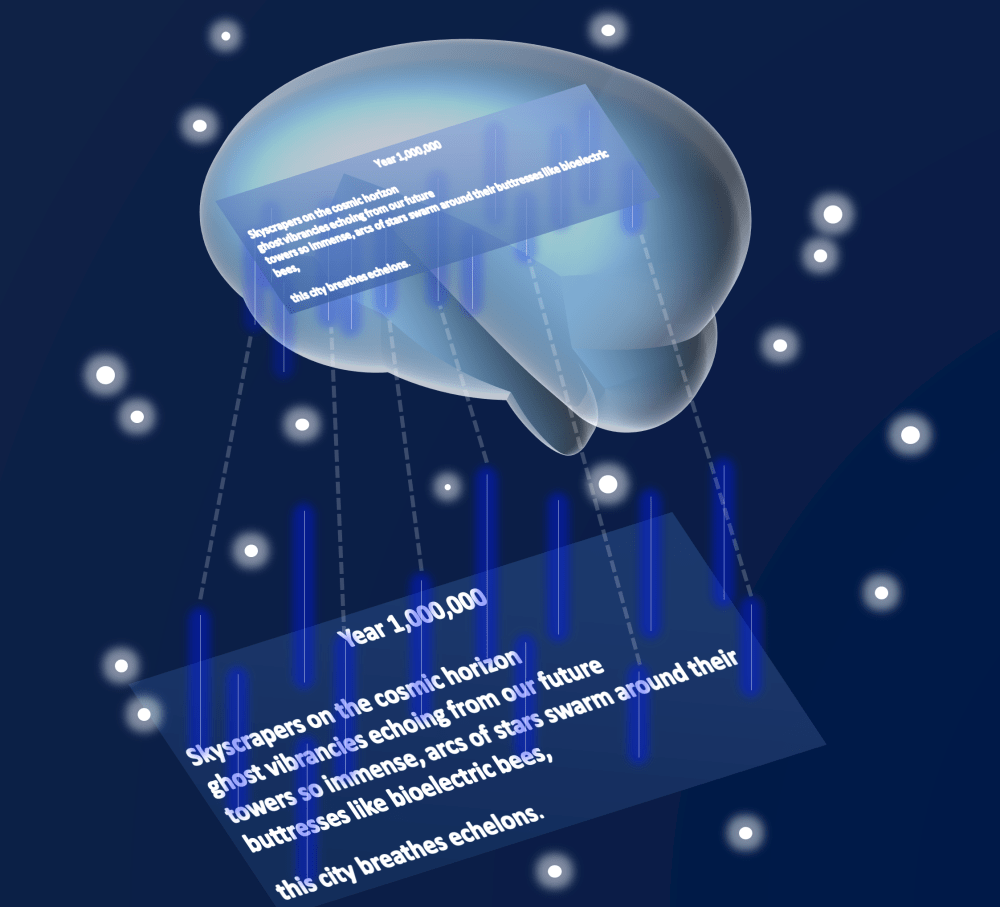

Year 1,000,000

Year 1,000,000

Jupiter Brain

Jupiter Brain

Don’t Spook the Snuffler

Don’t Spook the Snuffler

Endodermal

Endodermal

Kaleidaelectrica

Kaleidaelectrica