PDF version: Notes on Ultrasound Physics and Instrumentation – by Logan Thrasher Collins

Fundamentals of ultrasound waves

Sound waves such as those in ultrasound are longitudinal waves where particles oscillate backwards and forwards along the wave’s direction of propagation. This forms regions of higher (compression) and lower (rarefaction) density. Sound waves occur through the exchange of kinetic energy from molecular movement with the potential energy from elastic compression and stretching of bonds.

The speed of sound c depends on the medium. For example, in air c = 330 m/s while in water c = 1480 m/s. The frequency of a sound wave depends on the source producing it. Frequency is measured in Hertz (Hz) where 1 Hz = 1 cycle/second. Sound waves with frequencies greater than or equal to 20 kHz are referred to as ultrasound. The wavelength of a sound wave is λ = c/f. It is measured in mm (or other units of length). A sound wave’s phase describes what position the wave starts at within a cycle of oscillation and is measured in degrees or radians. Phase shifts are typically measured relative to a phase of 0° (or 0 rad). A sound wave’s amplitude corresponds to its “loudness” and describes the height of the wave’s peaks (or depth of its troughs). Cosine-based or complex exponential equations can describe sound waves in a similar way as they describe electromagnetic waves. These equations include amplitude as a coefficient, frequency as a factor multiplied by time, and phase shift as a term added to time.

Ultrasound pressure, power, and intensity

A sound wave’s excess pressure is the difference between its peak amplitude and the normal ambient pressure of the medium. When a medium is compressed, the excess pressure is positive and when it is rarified, the excess pressure is negative. In practice, the ambient pressure is often quite low and can be ignored, in which case pressure is used rather than excess pressure. Excess pressure and pressure are measured in Pascals (Pa), which are equivalent to N/m2.

When an ultrasound wave passes through a medium, it deposits energy (measured in Joules) into said medium. The rate at which a source produces this energy is the power, which is measured in Watts or J/s. An ultrasound wave’s power is unevenly distributed across the beam and often is more concentrated near the beam’s center. Intensity is a measure of the power flowing through a unit area perpendicular (or normal) to the wave’s direction of propagation and is measured in W/m2 or W/cm2. Intensity is proportional to the wave’s pressure squared (I ∝ p2).

Ultrasound and its medium

As mentioned, the medium (material) an ultrasound wave passes through determines the sound’s speed of propagation. Specifically, the material’s density and stiffness determine the speed of sound propagation. Density ρ is often measured in kg/m3. For instance, bone’s density ρbone = 1850 kg/m3 and water’s density ρwater = 1000 kg/m3 (or 1 g/cm3). Stiffness k describes how much a material resists deformation by force F. It equals the amount of pressure (stress) needed to change the thickness of a material by a given fraction and is measured in Pa. The ratio of change in thickness ΔL over original thickness L0 is called tensile strain ε. The increase (or decrease) in length of a material due to applied force is denoted ΔL = L – L0. Stress σ or fractional change in thickness is given by change in thickness divided by original thickness of the sample. Stress over strain is the elastic modulus E (also called Young’s modulus). Here, A is the cross-sectional area of a sample perpendicular to the applied force. Note that these formulas apply only for tensile stress (which induces tensile strain), the type of stress where a material is compressed or elongated.

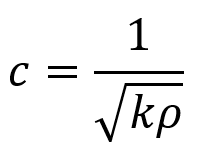

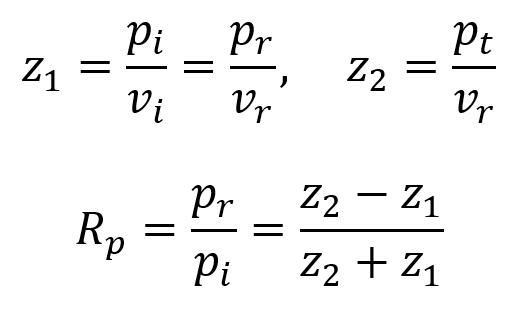

The relationship between a sound wave’s speed and the properties of density and thickness can be modeled by masses on springs where ρ = m = density (corresponding to masses in the model) and k = stiffness (corresponding to the spring stiffness in the model). The relationship between c, ρ, and k is given by the following equation.

As a result of these properties, the speed of sound varies in different tissues. A table of the approximate speeds of sound across selected tissues is provided.

Acoustic impedance z measures the response of a medium’s particles in terms of their velocity v to a sound wave of a given pressure p. Acoustic impedance can also be expressed in terms of density and stiffness or in terms of density and the sound’s speed. The latter form of definition is called the characteristic acoustic impedance of the tissue. It has units of kg m–2 s–1, also called rayl.

Ultrasound reflection and refraction

When an ultrasound wave traveling through a medium of acoustic impedance z1 encounters a new medium of different acoustic impedance z2, some of the wave is transmitted and some is reflected back. The equations in the following discussion will initially assume that the wave approaches the interface at a 90° angle (perpendicular) until stated otherwise.

To maintain continuity across the interface, the following equations must hold. Here, pi and vi are initial pressure and velocity, pr and vr are reflected pressure and velocity, and pt and vt are transmitted pressure and velocity.

Additionally, the intensity transmitted It across the interface equals the incident intensity Ii minus the reflected intensity Ir.

By using the equation for the definition of acoustic impedance z = p/v, the following two equations are true. Algebraically manipulating these equations leads to the third equation below. Rp is called the amplitude (or pressure) reflection coefficient of the interface. It is important because it decides the amplitude of the echoes produced at various interfaces within the tissue.

Note that if the acoustic impedance of the first medium is greater than the acoustic impedance of the second medium (i.e. z1 > z2), then Rp is negative and the reflected wave is inverted (across the x axis). For most interfaces between soft tissues, Rp is quite small and so most of the wave is transmitted to produce further echoes deeper within the tissue. This is useful for ultrasound imaging. Since the interface between air and soft tissue has a much larger Rp, the ultrasound source must be placed in direct contact with the patient’s skin to avoid air blocking transmission. This also means that gas-containing tissues like lungs and gut effectively block imaging beyond the region with the gas.

Another way to describe reflection is in terms of the intensity reflection coefficient RI. Since I ∝ p2, this means that RI = Rp2.

Since the incident intensity is Ii = It + Ir and the transmitted intensity is It = Ii – Ir, one can also define an intensity transmission coefficient TI as the first equation below. Since the transmitted pressure is pt = pi + pr, one can also define a pressure transmission coefficient Tp as the second equation below.

It is useful to realize that, because energy at interfaces must be conserved, the following equation holds true.

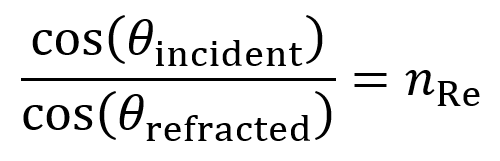

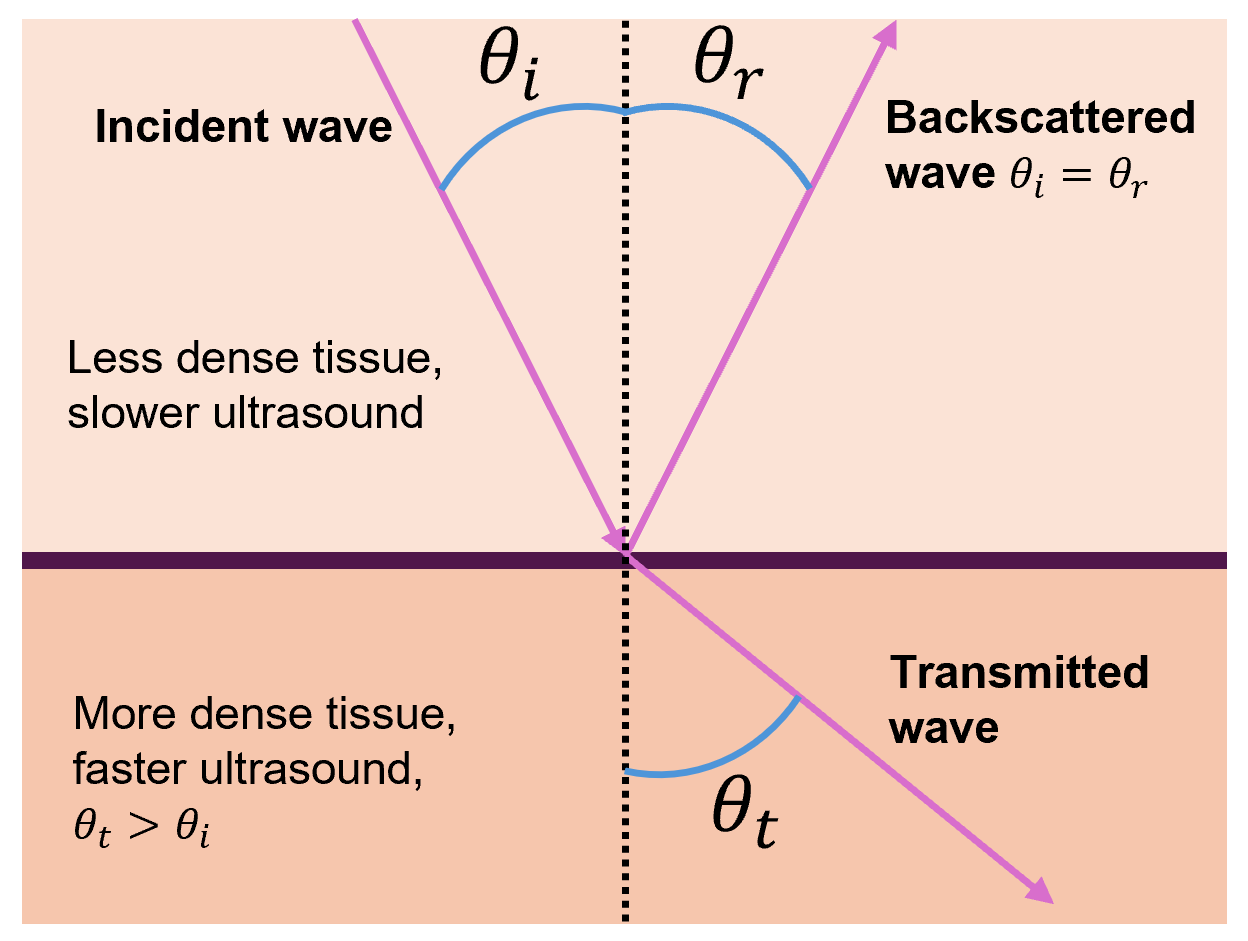

But ultrasound waves often do not approach interfaces at a 90° angle, so the equations in this section must be modified via trigonometry to account for other angles. First, note that the incident angle θi will equal the backscattered angle θr (this is true in the 90° case as well).

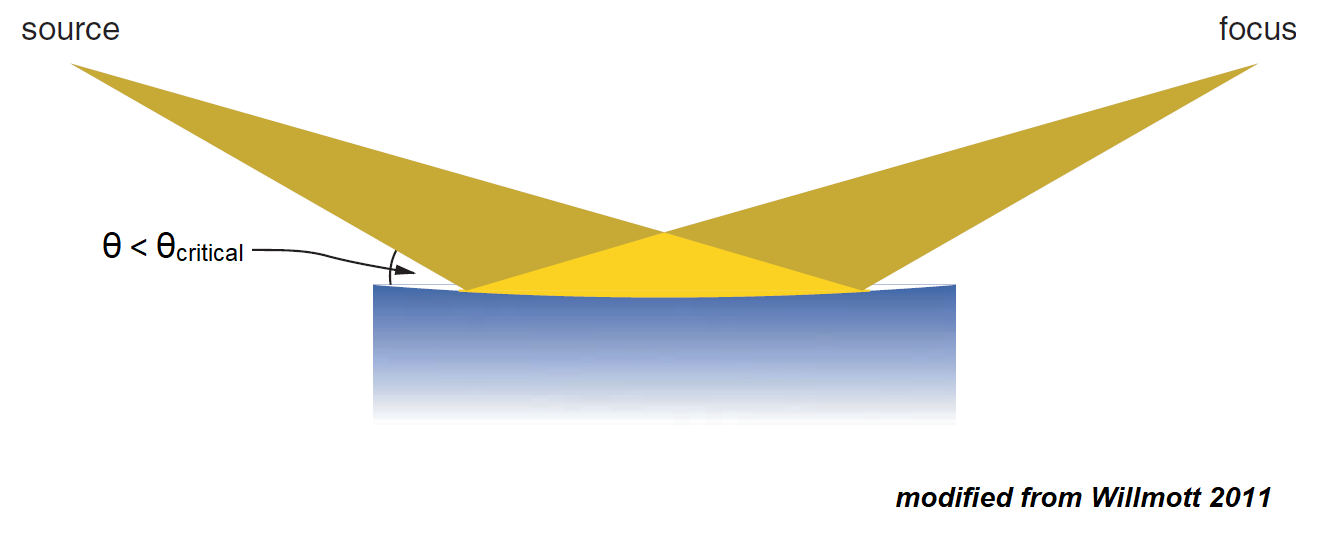

When a sound wave in a less dense tissue (slower sound wave) crosses into a tissue of greater density (faster sound wave), the transmitted wave bends away from the normal and thus θt > θi.

Likewise, when a sound wave in a tissue of greater density (faster sound wave) crosses into a tissue of less density (slower sound wave), the transmitted wave bends towards the normal and thus θt < θi.

Ultrasound scattering

When ultrasound encounters an object which is small compared to the wavelength, it scatters in all directions, though slightly more energy is typically backscattered towards the transducer than away from it. Scattering specifics depend on the shape, size, and acoustic properties (z, k, ρ) of the object.

When many similar small objects are close together (e.g. red blood cells), constructive interference can occur, which is useful. In the case of the blood, this is the basis for Doppler ultrasound, which measures blood flow. By comparison, when many small objects are far apart, complex interference patterns occur. This leads to a phenomenon in images known as “speckle”, which is usually (but not always) considered a form of undesirable noise.

Absorption and relaxation of ultrasound

As ultrasound moves through tissue, it loses energy due to absorption, resulting in heat. There are two ways this occurs: relaxation absorption and classical absorption. The effects of relaxation absorption are typically much more dominant.

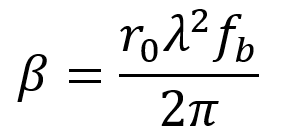

Relaxation absorption depends on the elastic properties of tissue, occurring when the tissue returns to its original state after rarefaction or compression by ultrasound. This is quantified by the relaxation time τ = 1/fr, which is how long the tissue takes to return to its original state after the ultrasound’s effect.

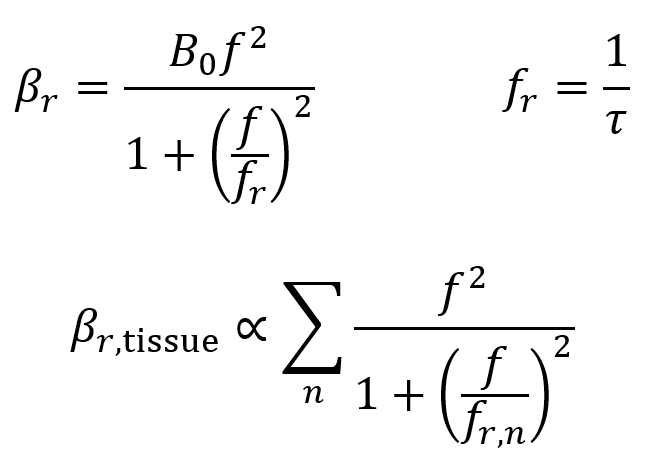

Relaxation is characterized by a relaxation absorption coefficient βr which is given by the first two equations below. Here, fr is the frequency of relaxation, f is the frequency of ultrasound, and B0 is a material-specific constant. In practice, tissues contain a range of values of τ and fr, so the third equation below is a more general formula where the overall relaxation absorption coefficient is proportional to the sum of the various contributions. Higher values of βr mean more energy is absorbed into the tissue.

It is useful to note that in tissues, the relationship between the relaxation absorption coefficient βr and the frequency f is approximately linear.

Classical absorption is less important in tissues since, at clinical frequencies, the relaxation absorption is strongly dominant as mentioned. That said, overall absorption does consist of a combination of relaxation and classical absorption (though the latter may be approximated away sometimes). Classical absorption occurs because of friction between particles as they are displaced by ultrasound, causing loss of energy to heat. This loss is characterized by the classical absorption coefficient βclass ∝ f2.

Attenuation coefficients

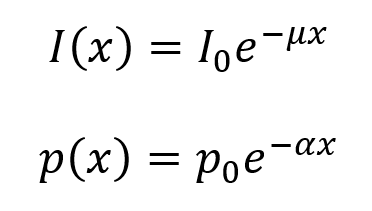

When an ultrasound beam propagates through tissue, the sum of the absorption and scattering is described as attenuation, which causes an exponential decrease in the pressure and intensity of the ultrasound as a function of the propagation distance x through tissue.

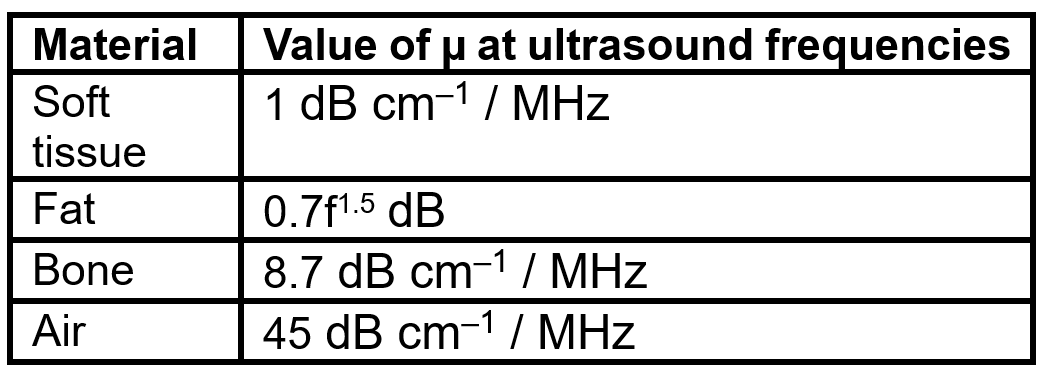

The following equations describe the loss of ultrasound intensity and pressure as the wave moves through tissue. Here, µ is the intensity attenuation coefficient and α is the pressure attenuation coefficient. The value of µ is equal to twice the value of α (so, µ = 2α). Both have units of cm–1, though the value of µ is often given in units of decibels (dB) per cm, where the conversion factor is µ(dB cm–1) = 4.343µ(cm–1). It is useful to note that each 3 dB decrease corresponds to a decrease in intensity by a factor of 2.

Approximate frequency dependences of µ are given in the table below. As an example, in soft tissue, the value of µ = 1 dB cm–1 for 1 MHz ultrasound and µ = 2 dB cm–1 for 2 MHz ultrasound. Note that the value of µ for fat is calculated differently than the others via the equation µ(f) = 0.7f1.5 dB.

Ultrasound transducers

Ultrasound imaging is performed using ultrasound transducers. A gated frequency generator first produces short periodic voltage pulses, which are then amplified and fed into the transducer via a transmit-receive switch. Because the transducer transmits high power pulses and receives low intensity signals from the reflected ultrasound waves, the transmit and receive circuits must be isolated from each other. Amplified voltage is converted by a shaped piezoelectric material (typically lead zirconate titanate, which is abbreviated PZT) in the transducer into a mechanical pressure wave which is transmitted into the tissue.

After reflecting and scattering from boundaries within the tissue, pressure wave signals return to the transducer and are converted back into voltages by the piezoelectric material. The voltages must pass through low-noise preamplifier before digitization. Further amplification and signal processing facilitates display of images on a computer.

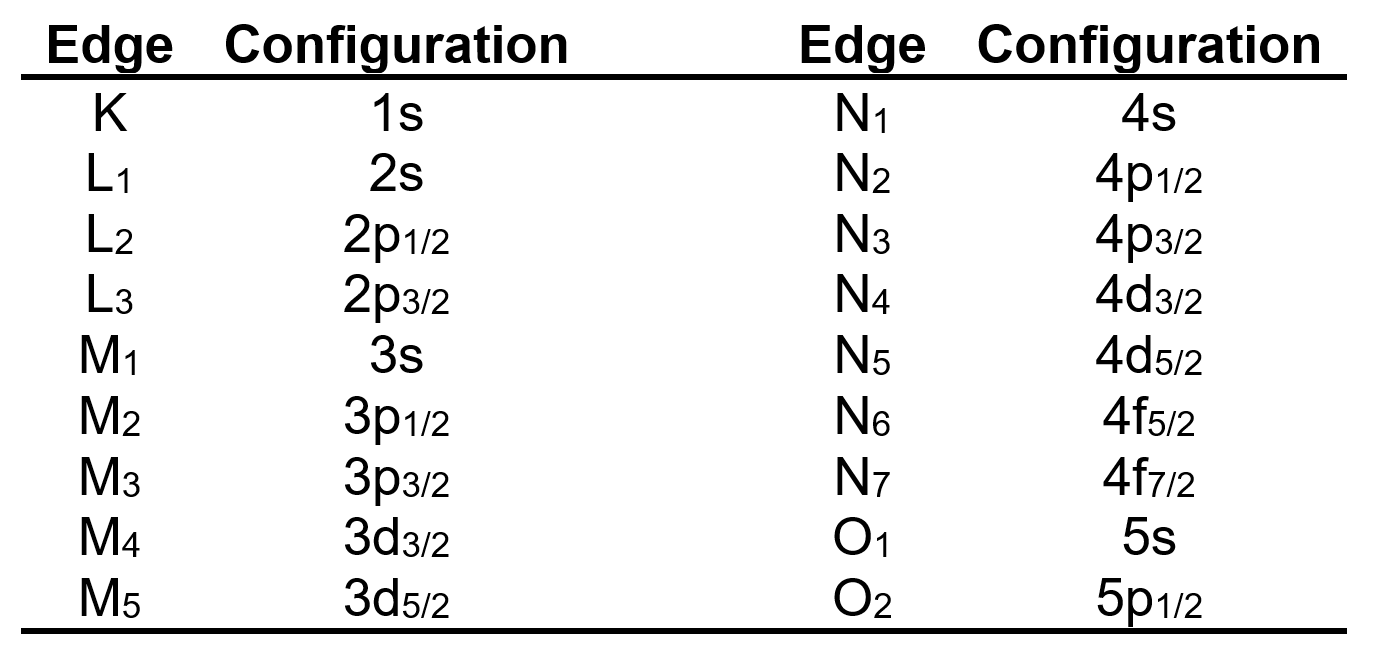

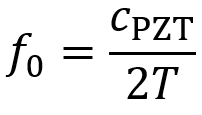

When oscillating voltage is applied to one end of shaped PZT material, the thickness of the PZT element oscillates at the same frequency as the voltage. By placing this element in contact with skin, mechanical pressure waves are transmitted into tissue. The element has a resonant frequency f0 which is determined by its thickness T and the speed of the ultrasound wave in the PZT material cPZT. The value of cPZT is ~4000 m/s.

For most ultrasound devices, the transducer element’s thickness must be designed to equal one half the wavelength of ultrasound in the PZT material λPZT, so T = λPZT/2. This facilitates use of the resonant frequency.

Because of the much higher acoustic impedance of PZT material compared to skin (~18 times higher), a large amount of the energy would be reflected if the PZT was placed directly onto the skin’s surface. This would mean the mechanical wave traveling into the tissue would lose most of its energy.

To prevent this energy loss from happening, transducers possess a matching layer with a zmatching value between zskin and zPZT as given by the equation below. The thickness of the matching layer is typically made to be 1/4 of the ultrasound’s wavelength in its material T = λmatching/4. All this improves the transmission and reception efficiency. Sometimes multiple matching layers are used to further improve efficiency.

At the back of a PZT element, there is a damping layer, typically made of some backing material and epoxy. This damping layer prevents the PZT from continuing to oscillate (at a decaying rate) after each voltage pulse. This continued oscillation would blur the boundaries between the short pulses, which can decrease axial resolution (as will be described soon).

Although transducers have a central frequency f0, they typically cover a range of frequencies (e.g. a 3 MHz transducer might cover a range of 1-5 MHz). Higher mechanical damping leads to broader transducer bandwidth. Transducer bandwidth is described as the frequency range over which the sensitivity is greater than half the maximum sensitivity level. The relationship between bandwidth and f0 is often quantified by the quality factor Q, which is the ratio of f0 to the bandwidth. Low values of Q mean larger bandwidths. Note that 2f0 is the second harmonic frequency.

Beam geometry and resolution

FUS transducers produce a very complicated wave pattern close to the face of the transducer (the near-field or Fresnel zone). This complicated pattern is not usually useful since it has many parts where the intensity is zero. Beyond the near-field zone, the wave pattern is much simpler and decays exponentially with distance (the far-field or Fraunhofer zone). The boundary between the two zones is called the near-field boundary (NFB) and occurs at a distance ZNFB away from the face of the transducer. The following equation (where r is the radius of the transducer) can be used to calculate the ZNFB value.

After the NFB, the FUS beam diverges (spreads out laterally) with an angle of deviation θ which is given by the equation below.

For the far-field zone, the lateral shape of the beam approximates a Gaussian function. The full width at half maximum (FWHM) defines the lateral resolution of the beam. It is given by the equation below, where σ is the standard deviation of the Gaussian. This value is unique to each FUS beam at the specific desired depth. It can be calculated by the following equation.

Single element transducers also produce ultrasound side lobes where the first zero of the side lobe at angle φ is the same equation as the FUS beam’s divergence angle equation. In ultrasound imaging, the side lobes can cause artifacts if they are backscattered from tissue outside of the imaged region.

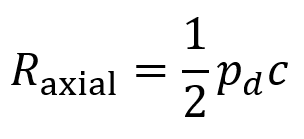

Axial resolution is the closest distance two boundaries can be relative to each other (in a direction parallel to the FUS beam’s propagation) while still allowing them to be resolved as two distinct features. It is given by the equation below where pd is the pulse duration and c represents the speed of the ultrasound in the tissue.

The reason that axial resolution works this way is because the echoes of beams returning from two different boundaries are distinguishable so long as these boundaries are spaced widely enough that they do not overlap in time.

Some typical values of axial resolution are 1.5 mm at a frequency (1/c) of 1 MHz or 0.3 mm at a frequency of 5 MHz. But it should be noted that attenuation of the FUS increases at higher frequencies, so there is an important tradeoff between penetration depth and axial resolution. (Very high frequencies such as 40 MHz can be used for imaging the skin at high resolution).

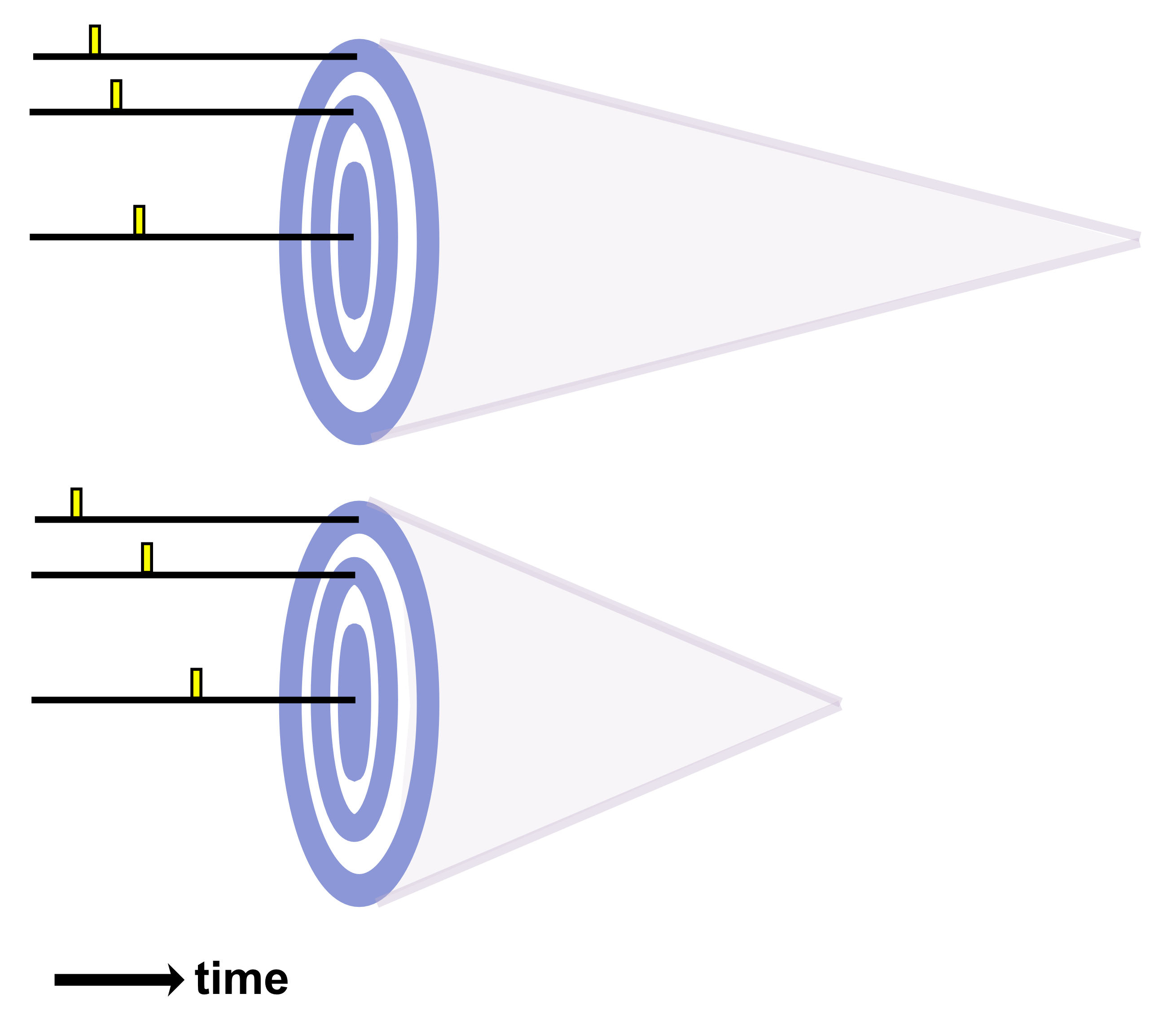

Single flat ultrasound transducers possess relatively poor lateral resolution. Concave curved transducers can achieve better resolutions. (It should be noted that the transducer equations above may be somewhat altered in the case of curved transducers rather than flat transducers). To make a curved transducer, one can add a curved plastic lens in front of the piezoelectric element or the piezoelectric element itself can be made in a concave curved shape.

The shape of a transducer’s curvature can be described by an “f-number”, which is a value equal to the focal distance divided by the aperture dimension where the aperture dimension is determined by the size of the transducer element.

Lateral resolution for a bowl-shaped curved (focused) transducer is calculated using the following equation below where λ is the ultrasound wavelength, F is the focal distance, and D is the diameter of the transducer. The focal distance F is where the lateral beamwidth is narrowest and is approximated as the radius of curvature (ROC) of the lens or PZT element. This approximation is valid except in the case of very high curvature.

When deciding on the focusing power of a transducer, there is a compromise between high spatial resolution and depth over which good spatial resolution is achievable. For a strongly focused transducer, locations further away from the beam’s focal plane diverge more sharply than for a weakly focused transducer. This can be quantified by the on-axis depth-of-focus (DOF) which equals the axial distance over which the beam’s intensity is at least 50% of its maximum value.

Transducer arrays

Contemporary FUS systems typically use arrays consisting of many small piezoelectric elements (rather than single-element transducers). These arrays allow 2D imaging via electronic steering of the beam through tissue while the transducer is held at a fixed position. Sophisticated electronics produce a dynamically changing focus during pulse transmission and signal reception, which maintains high resolution throughout the image. Linear and phased array transducers represent the two main types of arrays.

A linear array consists of many (often 128-512) rectangular piezoelectric elements where the space between elements is called kerf and the distance between their centers is referred to as pitch. Each element is mechanically and electrically isolated from its neighbors by filling the kerf regions with acoustically isolating material. The elements are not focused. Pitch is designed to range from λ/2 to 3λ/2 (where λ is ultrasound wavelength in tissue). Linear arrays are usually about 1 cm wide and 10-15 cm long.

Linear arrays work by using separate voltage pulses to excite a small number of elements at slightly different times where the outer elements are excited first and the inner elements are excited after a short delay. This creates an effectively curved wavefront with a focal point at a certain distance from the array. After all backscattered echoes have been received, another beam consisting of a distinct subset of elements performs the same steps. This is repeated in sequence until all of the groups of elements have completed the procedure. If even numbers of elements were used for each group, the entire process can be repeated again with odd numbers of elements to cover the focal points between those acquired before.

Linear array focusing occurs only in one dimension. By contrast, the elevation plane (the direction perpendicular to the image plane) cannot be focused unless a curved lens is included to produce focus in this dimension. Linear arrays are most often used for applications involving large fields of view and relatively low penetration depth.

Phased arrays are typically around 1-3 cm in length and 1 cm in width. They are used in applications like cardiac imaging where there is only a small region of the body through which the ultrasound can enter without running into bone or air.

As with linear arrays, phased arrays apply voltage pulses at slightly varying times to excite elements and produce an effective wavefront with a certain focal length. But phased arrays must employ beam steering to reconstruct a full 2D image. This occurs by changing the pattern of excitation to sweep the effective wavefront beam across a range of directions to cover the image plane.

Phased arrays also employ a process called dynamic focusing to optimize lateral resolution over the full depth of imaged tissue. This involves dynamically changing the number of elements used to produce a wavefront with varying focal lengths. At deeper regions in the tissue, the number of elements needed to position the focus (where optimal lateral resolution is achieved) is higher than at shallower regions in the tissue. Dynamic focusing allows high lateral resolution across the full depth of the scan. However, dynamic focusing is relatively slow since multiple scans are needed to build up a single line of the image. It should be noted that the length of each element determines the “slice thickness” for the image’s elevation dimension.

There are also multidimensional transducer arrays which include extra rows of transducer elements. These multidimensional arrays can focus in the elevation dimension without the need for curved elements or lenses (though they are more complicated devices). Multidimensional arrays with a small number of extra rows (e.g. 3-10) are referred to as 1.5 dimensional arrays. These 1.5D arrays can facilitate some level of focusing in the elevation dimension, though to a limited extent. When multidimensional arrays possess a large number of extra rows (up to the number of elements in each row), they are referred to as 2 dimensional arrays. These can acquire full 3D image data without needing to be moved from their initial position.

Annular arrays represent another class of transducer array. They are useful at very high frequencies (>20 MHz) since linear or phased arrays are quite difficult to create for these frequencies. Annular arrays consist of concentric rings of piezoelectric material alternating with rings acoustically isolating material. Beam forming is accomplished using an analogous strategy to that of phased arrays. The outermost rings are excited first and the innermost rings last, producing an effective focus. Because annular arrays require mechanical motion to sweep the beam through tissue for reconstruction of images, commercially available devices have been developed to precisely control this motion.

When transducer arrays receive signals, they pass through an amplifier to strengthen them before digitization. However, such amplifiers do not provide linear gain for signals with a dynamic range that exceeds 40-50 dB. This is an issue because very strong signals appear from tissue boundaries near the transducer while much weaker signals appear from tissue boundaries deeper in the body. Weak signals can thus be lost when attempting to receive over larger dynamic ranges. A process called time-gain compensation (TGC) is employed to circumvent this issue. TGC increases the amplification factor as a function of time after transmission of an ultrasound pulse. As a result, the weaker backscattered echoes which come later are amplified to a greater degree than the stronger backscattered echoes which come sooner. TGC is controlled by the operator of the instrument, which usually comes with a variety of preset values for clinical imaging protocols.

Parameters for focused ultrasound in practice

There is no universally accepted definition of FUS dose, so various metrics of exposure are used to quantify how much ultrasound is delivered during a therapeutic session. Examples of such metrics (which will be discussed further below) include acoustic pressure or peak negative pressure, mechanical index, frequency, pulse repetition frequency (PRF), and intensity.

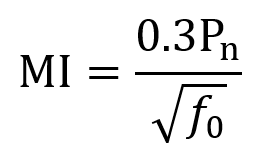

Peak negative pressure is often measured in MPa and describes the degree of rarefaction caused by the ultrasound wave in tissue. For low intensity focused ultrasound (LIFU), the greatest mechanical safety risk is from cavitation (bubble formation and collapse). To measure cavitation risk, the mechanical index (MI) is used. MI can be computed using the following equation where Pn is the peak negative pressure, f0 is the fundamental frequency, and the derating constant of 0.3 adjusts for tissue attenuation (~7% loss per cm per MHz) and has units dBcm–1MHz–1. After derating, 0.3Pn has units of MPa. FDA guidelines specify that MI should not exceed 1.9. MI itself is unitless.

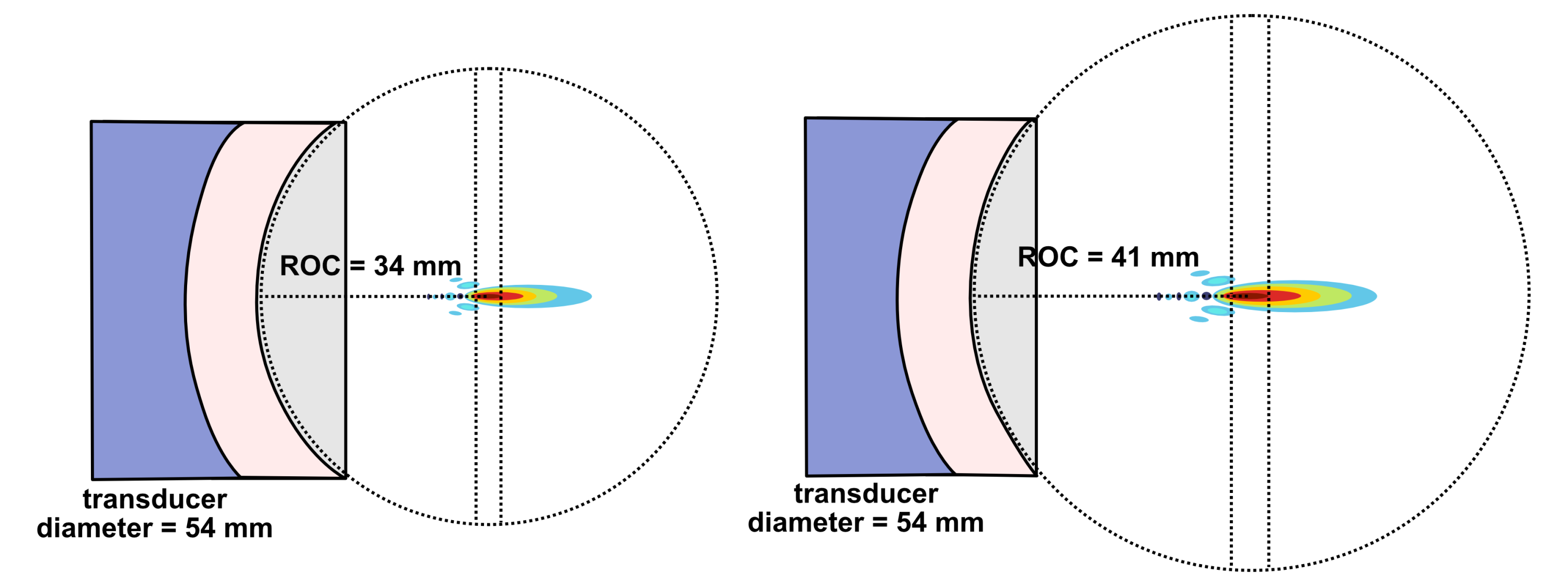

An ultrasound wave’s pulse’s duration (PD) is the number of cycles divided by the frequency. For instance, a pulse with 500 cycles of 500 kHz ultrasound would last for 1 ms. The pulse repetition interval (PRI) is the amount of time between the start of one pulse and the start of the next pulse (so it includes both the pulse and the pause after the pulse). Pulse repetition rate (PRR) also known as the pulse repetition frequency (PRF) equals 1/PRI. The pulse duty cycle (PDC) equals PD/PRI and is expressed as a percentage. PD typically ranges from microseconds to seconds, PRI from milliseconds to seconds, and PDC from <1% up to 70%.

One’s choice of a particular PD and PDC comes from two main factors: (i) the duty cycle can have varying neuromodulatory effects (excitatory or inhibitory) depending on its value and (ii) lower PDC values can be leveraged to limit total energy and heat deposition.

A pulse train is a series of pulses, for which the pulse train duration (PTD) equals the total number of pulses times the PRI. Typical PTDs range from less than 1 second to several minutes. The amount of time between the start of one pulse train and the start of the next is called the pulse train repetition interval (PTRI). The amount of time between pulse trains is called the interstimulus interval (ISI). The pulse train duty cycle (PTDC) equals PTD/PTRI.

It should be noted that the PTDC does not have a major influence on neuromodulatory effect, so the ratio is driven by safety such that the ISI is long enough to limit cumulative heating to reasonable levels.

Multiplying PDC by PTDC gives an overall duty cycle equal to (PD/PRI)(PTD/PTRI) which can be further multiplied by the average intensity of the pulses Iavg to obtain average temporal intensity Iavg_tp. FDA diagnostic safety guidelines state that average intensity should fall below 720 mW/cm2. So, Iavg_tp = (PD/PRI)(PTD/PTRI)Iavg generally should not exceed 720 mW/cm2.

Total ultrasound application time is the sum of the durations of all pulse trains plus ISIs. It typically ranges from less than 1 minute to over 60 minutes. Longer total ultrasound application time is thought to usually improve efficacy by depositing more energy, though this may not always be true. Energy per unit time might play a more significant role in efficacy, but this is an ongoing area of investigation.

Frequency (or fundamental frequency f0) is the primary frequency of FUS passing through the tissue. It is typically measured in kilohertz (kHz) or megahertz (MHz). In human neuromodulation applications, frequency typically ranges from 200-700 kHz (or 0.2-0.7 MHz), providing an acceptable tradeoff between amount of energy entering the brain and the size of the focal region. The reason that the upper limit of frequency for human neuromodulation is typically ~700 kHz is because FUS energy attenuation by the skull at 700 kHz is ~75% (though this varies depending on skull morphology) and keeps increasing at higher frequencies.

Recall from the equations in the earlier discussion that lateral resolution involves wavelength λ (and f = c/λ), so frequency influences the focal region’s size. Also discussed earlier, frequency influences the distance from the transducer to the near-field boundary (ZNFB). Frequency itself is generally not believed to contribute to neuromodulatory effects in a direct fashion, though this is still under investigation. So, the f0 value is usually selected to create a focal volume of a desired size at a given depth.

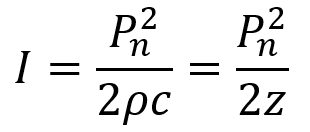

Intensity is defined as power per unit area (and recall the unit of power is Watts or J/s) and is the rate at which energy is transferred by the FUS wave. For ultrasound at any given point in time during the wave cycle, intensity is proportional to the square of the acoustic pressure as described by the equation below where P is the acoustic pressure, ρ is the density of the medium, and c is the ultrasound speed in the medium. Recall that ρc = z, the acoustic impedance. Acoustic intensity is usually measured in watts per square centimeter (W/cm2).

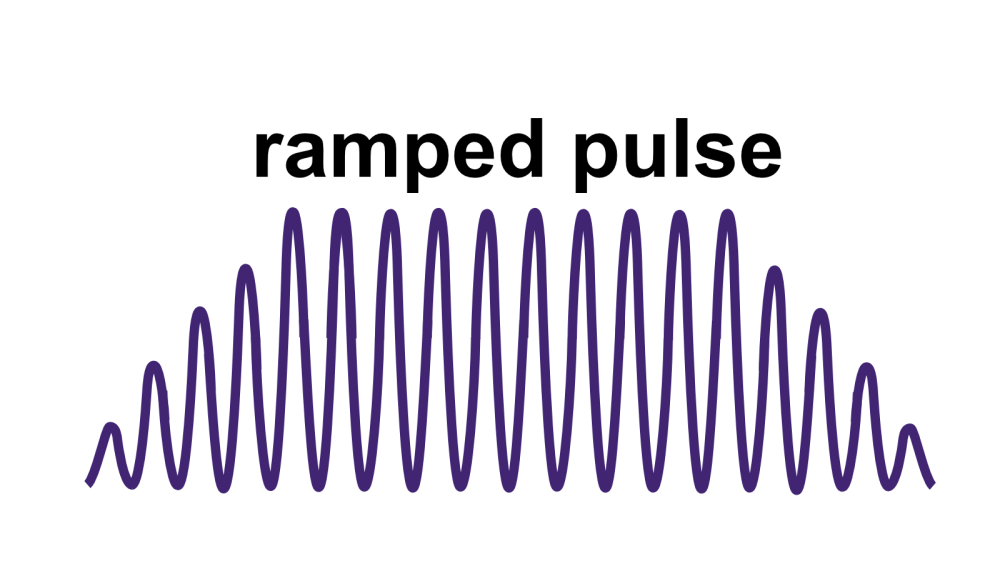

Beyond instantaneous intensity, FUS is often measured by spatial peak pulse average intensity (ISPPA) and by spatial peak temporal average intensity (ISPTA). ISPPA is the average intensity experienced during a single ultrasound pulse. Note that I does not equal Pn2/2z in the case of a ramped pulse. To determine average intensity (ISPPA) for ramped pulses, the integral of intensity across the pulse is divided by the pulse’s duration PD. Ramped pulses distribute energy more smoothly and help mitigate auditory confounds for LIFU applications.

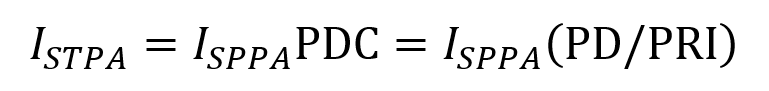

ISPTA represents the average intensity of the FUS beam at the point where it is strongest averaged over the pulse duration while accounting for any off periods. It is described by the following equation consisting of the ISPPA multiplied by the PDC (which is the fraction of PRI that the pulse is turned on).

References:

1. Legon, W. & Strohman, A. Low-intensity focused ultrasound for human neuromodulation. Nat. Rev. Methods Prim. 4, 91 (2024).

2. Smith, N. B. & Webb, A. Introduction to Medical Imaging: Physics, Engineering and Clinical Applications. (Cambridge University Press, 2010).