an exploration by Logan Thrasher Collins.

Algebraic manipulation of mathematical objects provides a rich array of tools for deriving insights about said objects. Graph theory concerns networks of vertices and edges and finds applications in diverse areas such as computer science, quantitative sociology, electrical engineering, and neurobiology. The use of algebraic methods in graph theory has received surprisingly little attention. While mappings are sometimes studied in graph theory, such transformations are often considered in the abstract, without a method for describing the content of any given mapping. Here, I define an algebraic framework for specifying transformations between graphs. This framework might be extended to further capitalize upon the tools of analysis and abstract algebra, leading to potential new paths of investigation.

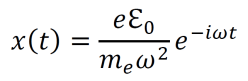

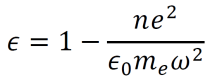

Let G and H be simple, labeled graphs. The transformation ϕ(G):𝔾→𝔾 is a mapping which transforms G into H. (Here, 𝔾 represents the set of all simple, labeled graphs). To specify the precise content of this process, I define a general formula for graph mappings. Note that any term may take on either a positive or a negative value. Positive terms indicate the creation of a new vertex or edge within H, while negative terms indicate the removal of an existing vertex or edge from G. In this formula, v∈{V(G),V(H)} and e∈{E(G),E(H)}.

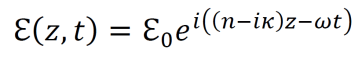

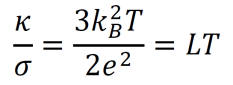

In order for the equation above to be defined, any edge must connect a pair of vertices in H. That is, no edge e can be created without also creating a pair of corresponding vertices that are connected by e. Below, I will provide a specific example of a mapping between graphs to show this formula’s mechanics.

![]()

Figure 1 Illustrative example of an algebraic graph mapping ϕ(G)=H and its corresponding labeled graphs.

The algebraic manipulations enabled by this approach remain somewhat limited since every new vertex and edge and every deleted vertex and edge must be explicitly specified. However, as with manipulations of other mathematical objects, taking advantage of patterns can allow abstraction to larger and more complicated systems. For example, sequences and series are often utilized for such purposes in the field of analysis. To move towards analogous investigations on graphs, I will describe a framework for graph labeling which eases the manipulation of complex networks using my algebraic technique.

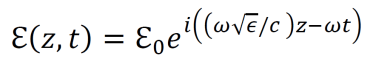

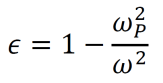

Let 𝒵 represent a set of “potential vertices” equipped with labels corresponding to the integers. It should be noted that this setup allows for infinite isomorphic graphs with different labelings to be constructed. Each point in 𝒵 is labeled as x∈ℤ. The points x∈𝒵 define the set of possible vertices v∈H which might be created when ϕ operates upon G. In this way, symbolic extrapolations to large networks can be made.

Figure 2 (A) The layout of “potential vertices” described by 𝒵 with bounds x∈[-5,5]. (B) An example of a labeled graph defined on 𝒵 with the same bounds.

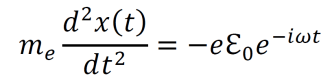

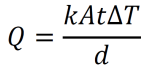

Using the labeling scheme 𝒵, functions on ℤ can facilitate the construction of complex networks according to defined rules. Let the variable x take on integer values such that x∈ℤ. To map between graphs on 𝒵, use functions which satisfy F𝒵:ℤ→ℤ to specify the vertices and edges of H. Note that such functions will create infinite graphs unless bounds are defined on x. To facilitate the construction of networks, this scheme will follow three useful rules. (1) If repeated vertices and edges are created, the copies of the repeated vertices and edges will be ignored. (2) If a nonexistent vertex or edge is subtracted, giving a negative vertex or edge, the negative object will be ignored. (3) Any edges or vertices which do not belong to G or H will be ignored.

Figure 3 (A) The graph G consists of a single vertex v(0). (B) The function F𝒵 maps G to a graph H using the labeling scheme 𝒵. Edges are created linking v(3) and the rest of the vertices, all negative-labeled vertices edges incident with v(3) are removed, and then all edges linking v(0) and any existing negative-labeled vertices are created. (C) Isomorphism on H to provide a cleaner visualization of the result.

Here, I have developed an algebraic toolset for describing mappings between graphs. This toolset allows the creation of new vertices and edges as well as the removal of existing vertices and edges. To allow rapid generation of networks with many vertices and edges, I have provided a method for consistently labeling graphs that works synergistically with the core algebraic technique. This method may provide the basis for more generalized explorations which utilize such mathematical resources as groups and group-like structures. Because the method lends itself to creating infinite graphs, it may also stimulate investigation from the perspective of analysis using concepts like limits and convergence. The relationships between my algebraic graph mappings and matrix-based representations of graphs may also provide new territory. Applied computational fields may benefit from the mapping technique since it provides an alternative set of resources for investigating and modeling networks. Algebraic graph mappings may provide a nucleation point for a myriad of possible research directions.

Disclaimer: because I come from a biological background and have very limited formal mathematical training, this text may appear quite rough to more mathematically-experienced individuals. However, I feel that the technique has potential to develop further and be applied to problems in science and engineering. I would welcome any constructive critiques so long as they are presented in a respectful manner.