Most ideologies include methods for finding reasons to live. But after seeing historical tragedies in which such methods have led to tremendous suffering, some have given up on the idea of purpose. This is not an entirely unreasonable response, but I would argue that it still represents an unjustifiably pessimistic outlook. Although most systems of existential meaning suffer from crippling flaws, such flaws do not invalidate the possibility of purpose. Religious, political, and philosophical approaches have been applied towards resolving the question of existential purpose (Triandis, 2008). Each system possesses certain merits, but they are incomplete since their theoretical frameworks lacks rigor and data. In this essay, I will discuss a toolset and a general philosophical framework which may aid efforts to construct a meaningful world. I propose that existential meaning arises from specific computational structures encoded in matter which can be understood and engineered using the empirical and self-correcting process of scientific inquiry.

Religious thinkers suggest that specific dogma associated with a given belief system provide meaning. They argue that the purpose of life involves fulfilling certain natural laws which they associate with deities, scriptures, and prophets. However, religious ideologies lack strong empirical support for their dogmas. This may arise from religious doctrines not including effective ways for them to evolve as new knowledge is acquired and circumstances change (Emerson & Hartman, 2006). It should be noted that some religions possess a greater level of flexibility than others. For instance, followers of Hinduism have demonstrated openness to their religion evolving as scientific knowledge provides new insights about the universe. Varadaraja Raman has written on deconstructing the schism between Hindu spirituality and science by reinterpreting Hindu ideas as metaphors for scientific concepts (Raman, 2009). In addition, some followers of the Vedanta philosophy subscribe to a nondualist view of the universe and have made attempts to reconcile Hindu beliefs with new scientific findings (Dorman, 2011). However, other Hindu philosophies have remained bound to tradition, rejected concepts like evolution by natural selection, and even embraced radical postmodernist characterizations of rationality as a tool for oppression (Raman, 2012). Since many religions have exhibited staticity in their interpretations of purpose when new data contradicts their dogma, I propose that existing and past religions have created approximate models for purpose, but fallen short of their ultimate goals.

Political strategies for finding meaning often involve creating identity via tribal association with certain values while rejecting outgroups which deviate from said values. According to a meta-analysis performed by Jost et al., both conservatives and liberals possess existential motivations driven by specific fears associated with opposing values (Jost, Stern, Rule, & Sterling, 2017). For conservatives, the data indicated fear of governmental control, racial minorities, and social changes that conflict with traditional views. Among liberals, the data indicated that threatening circumstances trigger an increase in tendencies towards strong moralization of political issues. Across political affiliations, such tribalistic behaviors may correlate with the same psychologies which drive religious and philosophical approaches to uncovering existential meaning (Norris & Inglehart, 2011). This is not inherently wrong, but it does reframe politics as holding similarities to religion in that politics may only provide approximations in its pursuit of meaning. Furthermore, political techniques have so far failed to create stable utopian societies, though secular political systems have debatably realized improvements over theocratic systems (Lilla, 2008).

Stoic philosophers such as Albert Camus argue that accepting absurdity may represent a superior way of living (Camus, 2013). Stoicism seeks to ignore value and so avoid existential dread (Nagel, 1971). But stoicism is paradoxical in that it denies the phenomenological existence of value (Block, 1995; D. J. Chalmers, 1995; Nagel, 1974). Stoics may claim to live passively, but they will always fail to exercise consistency in this doctrine since value is a fundamental constituent of reality. Any entity will possess at least some degree of motivation, regardless of whether the entity wants to possess said motivations. The universal existence of motivation can be illustrated by causality in natural systems. For this argument, I take the nondualist position that consciousness is identical to specific physical processes and does not possess a supernatural component. Consider a rock which rolls down a hill and strikes a second rock. In this scenario, the second rock cannot prevent itself from having a reaction. Biological organisms are no exception to causality. From atoms to galaxies, the cosmos is driven by change. As much as a stoic may try to condition him or herself against reaction, physical reality remains intrinsically causal, so this task will ultimately be in vain.

To provide a contextual background for my proposal that existential meaning is encoded in matter, I will introduce a physical argument for panpsychism. Despite its past association with metaphysics, panpsychism is rekindling among contemporary thinkers as an explanation for consciousness (Strawson, 2006). Integrated information theory or IIT (Oizumi, Albantakis, & Tononi, 2014) is a mathematical formulation which seeks to quantify consciousness using the information arising from dynamical systems. Galen Strawson has argued that IIT implies panpsychism since all physical structures contain some amount of information (Strawson, 2006). Furthermore, Adam Barrett has proposed modifications to IIT which may help account for fundamental physical interpretations of the universe like quantum field theory (Barrett, 2014). Panpsychic descriptions of reality are reentering philosophical and scientific discourse as new data are acquired and new theoretical interpretations develop.

But many still view the idea that inanimate objects may possess primitive qualia as ludicrous. To counter this presumption, consider a fragment of quartz resting on a ridge. As the sun rises, photons excite the atoms on the crystal’s surface, causing thermal oscillations to propagate into the quartz. This thermal diffusion is modulated by crystallographic defects, causing a heterogeneous distribution of heat inside the rock. As dusk falls, the quartz fragment begins to cool, emitting heat at varying rates across the surface. The particular rates are influenced directly by this quartz specimen’s pattern of internal defects. Next, consider a mouse, also located on the ridge. As the sun rises, photons excite the retinaldehyde molecules in the mouse’s eyes, triggering signal transduction via electrochemical systems. This signal moves into the mouse’s brain, where it propagates through a series of neural pathways, causing a heterogeneous distribution of neural activity. Soon, the signal’s interaction with preexisting brain structures is translated into a motor action; the mouse blinks and looks away from the bright illumination. The particular motor response is modulated by the structural organization of this mouse’s brain at the given time. The quartz and the mouse both receive sensory inputs, process them according to internal properties, and then give motor outputs. Although the rock’s “brain” is much more disorganized and chaotic than the mouse’s brain, it operates by the same basic principles and could plausibly experience a primitive form of consciousness. As such, the possibility of panpsychism cannot be readily dismissed as absurd or metaphysical.

Another prominent objection to panpsychism arises from brain processes which occur in a subconscious fashion. For instance, activity in the primary visual cortex (V1) does not correlate with conscious visual experience except for a few special cases (Crick & Koch, 1995) (Boyer, Harrison, & Ro, 2005) (Boehler, Schoenfeld, Heinze, & Hopf, 2008). However, the presence of subconscious neural events does not necessarily indicate that the said events are subconscious from the viewpoint of their associated anatomies. Instead, anatomical structures like V1 may experience their own independent qualia. The full informational content of their perceptions may not be transmitted or translated into the brain areas like the prefrontal cortex (PFC) which can be identified with a patient’s sense of self (Mitchell, Banaji, & Macrae, 2005). Of course, some data does transfer into higher brain regions to facilitate processes like vision, but the information undergoes an extensive series of transformations before arriving at the PFC and other regions associated with conscious processing. For this reason, the “unconscious anatomies” objection is insufficient to invalidate panpsychism.

Under the assumption of panpsychism or the similar description provided by protopanpsychism (Chalmers, 2015), cognitive states are identical to configurations of matter and energy. As emotions like joy, anger, wonder, sadness, and love emerge from functional circuits in the brain, the same emotions may emerge from informationally equivalent circuits in other substrates like classical computers equipped with biologically-realistic software models or neuromorphic semiconductor devices (Koene, 2013). This reasoning applies to feelings of existential meaning as well. If the emotions associated with fulfillment and purpose are encoded in physical matter, then they represent an intrinsic property of the universe. As such, the possibility of existential meaning cannot be dismissed on the grounds that it arises as an irrational psychological construction, though psychological biases still must be taken into consideration.

Feelings of existential meaning come in many flavors and magnitudes, some of which may represent objectively “better” states than others. To explain this principle, I will describe several illustrative fictional scenarios. First, consider a venture capitalist named Aiko, a man who enjoys the thrill of financial competition. Aiko feels some level of fulfillment from his pursuits. Despite this, Aiko also experiences loneliness since he has not maintained close relationships with his family. Now consider Anastasia, a feminist intellectual who has made notable strides towards gender equality. By comparison to Aiko, Anastasia experiences a stronger sense of fulfillment from her work as well as lesser misgivings from the sacrifices she has made in other areas. In a somewhat fanciful exploration, consider an unbiased spirit which decides to inhabit Aiko’s mind and then Anastasia’s mind. This spirit is assumed to exhibit perfect rationality. Upon comparing the two people’s internal states, the spirit concludes that it would prefer Anastasia’s emotional experiences over Aiko’s emotional experiences. This account demonstrates the idea that purpose can manifest differently across individuals, that such differences can undergo objective comparison, and that some states may represent objectively superior qualia.

Despite this, I would argue that the events which trigger emotional states associated with purpose are irrelevant to existential meaning. Distinct sets of events can still cause distinct emotional states, but only the resulting emotions themselves define purpose. To understand this, consider a factory worker called Akhmed, who was born with a mutation which influenced his neural development such that he easily gains feelings of fulfillment even in mundane situations. Also consider an influential political leader named Carlos, who was born with an unfortunate susceptibility to clinical depression. Akhmed’s feeling of purpose in his monotonous factory work represents an objectively better state than Carlos’s sensation of meaninglessness even as Carlos facilitates widespread social improvements. Note that this scenario focuses upon the emotional states of the specific physical subsystems corresponding to Akhmed and Carlos, not on the physical subsystems corresponding to the people who Carlos has helped. The qualia involved in an emotion, rather than the causes for said qualia, are necessary for explaining the emotion’s value. Although meaning can vary across individuals, informatic circuits which underlie meaning may provide a route for quantifying purpose’s value and for pursuing existential fulfillment with greater methodological precision.

From a practical perspective, this proposal indicates that deliberate creation of positive emotional states associated with purpose is an intrinsically worthwhile pursuit, but also that this pursuit must undergo consideration in a larger context. I suggest that it may not always be ethical for a subsystem of the universe such as an individual human to create positive emotional states within herself if the process causes harm to others. Note that a full exploration of potential physical bases for morality is beyond the scope of this essay. But despite the conflicts raised by altering emotional states in a heterogeneously distributed manner, reconfiguring matter on larger scales towards positive emotional states represents a clearer imperative.

In some ways, earlier approaches to the question of existential purpose have already suggested the goal of reconfiguring matter towards meaningful emotional states. But certain religious, political, and philosophical approaches have demonstrated more success than others. In cases like Islamic fundamentalism, Christofascism (Sölle, 1970), Nazism, and social Darwinism, their attempts have backfired and caused widespread harm rather than improvement. But as mentioned, such approaches have suffered from poor theoretical and empirical rigor in their development. I would argue that using evidence-based methods towards creating a better tomorrow will facilitate the creation of policies, technologies, and ethical guidelines which possess sufficient theoretical and empirical rigor to simultaneously maximize the likelihood of widespread beneficial results and minimize the likelihood of widespread harmful results. Existential meaning is tied to physical reality and so can be engineered. In order to create existential meaning without falling prey to the same mistakes observed through history, we must utilize empirical methods to guide the construction of a bright future in which positive emotions are recognized as physical expressions of purpose and effective strategies for maintaining such emotions are implemented.

References

Barrett, A. (2014). An integration of integrated information theory with fundamental physics. Frontiers in Psychology. Retrieved from https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00063

Block, N. (1995). On a confusion about a function of consciousness. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 18(2), 227–247.

Boehler, C. N., Schoenfeld, M. A., Heinze, H.-J., & Hopf, J.-M. (2008). Rapid recurrent processing gates awareness in primary visual cortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105(25), 8742 LP-8747. Retrieved from http://www.pnas.org/content/105/25/8742.abstract

Boyer, J. L., Harrison, S., & Ro, T. (2005). Unconscious processing of orientation and color without primary visual cortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 102(46), 16875 LP-16879. Retrieved from http://www.pnas.org/content/102/46/16875.abstract

Camus, A. (2013). The myth of Sisyphus. Penguin UK.

Chalmers, D. (2015). Panpsychism and panprotopsychism. Consciousness in the Physical World: Perspectives on Russellian Monism, 246.

Chalmers, D. J. (1995). Facing up to the problem of consciousness. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 2(3), 200–219.

Crick, F., & Koch, C. (1995). Are we aware of neural activity in primary visual cortex? Nature, 375(6527), 121–123.

Dorman, E. (2011). Hinduism and Science: The State of the South Asian Science and Religion Discourse. Zygon®, 46(3), 593–619. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9744.2011.01201.x

Emerson, M. O., & Hartman, D. (2006). The Rise of Religious Fundamentalism. Annual Review of Sociology, 32(1), 127–144. http://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.32.061604.123141

Jost, J. T., Stern, C., Rule, N. O., & Sterling, J. (2017). The Politics of Fear: Is There an Ideological Asymmetry in Existential Motivation? Social Cognition, 35(4), 324–353. http://doi.org/10.1521/soco.2017.35.4.324

Koene, R. A. (2013). Uploading to Substrate‐Independent Minds. The Transhumanist Reader: Classical and Contemporary Essays on the Science, Technology, and Philosophy of the Human Future, 146–156.

Lilla, M. (2008). The Stillborn God: Religion, Politics, and the Modern West. Vintage Books. Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?id=nfSMDQAAQBAJ

Mitchell, J. P., Banaji, M. R., & Macrae, C. N. (2005). The Link between Social Cognition and Self-referential Thought in the Medial Prefrontal Cortex. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 17(8), 1306–1315. http://doi.org/10.1162/0898929055002418

Nagel, T. (1971). The absurd. The Journal of Philosophy, 68(20), 716–727.

Nagel, T. (1974). What Is It Like to Be a Bat? The Philosophical Review, 83(4), 435–450. http://doi.org/10.2307/2183914

Norris, P., & Inglehart, R. (2011). Sacred and Secular: Religion and Politics Worldwide. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?id=ObwtZ36m1hwC

Oizumi, M., Albantakis, L., & Tononi, G. (2014). From the Phenomenology to the Mechanisms of Consciousness: Integrated Information Theory 3.0. PLOS Computational Biology, 10(5), e1003588. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003588

Raman, V. (2009). Truth and Tension in Science and Religion. Beech River Books. Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?id=UggdrSiVvhsC

Raman, V. (2012). Hinduism and Science: Some Reflections. Zygon®, 47(3), 549–574. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9744.2012.01274.x

Sölle, D. (1970). Beyond Mere Obedience: Reflections on a Christian Ethic for the Future. Augsburg Publishing House. Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?id=zbeCGwAACAAJ

Strawson, G. (2006). Realistic monism: why physicalism entails panpsychism.

Triandis, H. C. (2008). Fooling Ourselves: Self-Deception in Politics, Religion, and Terrorism: Self-Deception in Politics, Religion, and Terrorism. ABC-CLIO. Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?id=GGdrumE1JuYC

only certain lanthanides possess the proper characteristics for this mechanism to occur (Ho3+, Er3+, Nd3+, and Tm3+) when commercially-available diode lasers are used (which usually have incident wavelengths of around 975 or 808 nm). The relevant energy levels are called G, E1, and E2 (for ground state, excited state 1, and excited state 2). Electrons in the E1 excited state have long lifetimes before they return to the ground state G. As such, after an electron is excited to E1, it remains there for long enough that it can be promoted to E2 by another photon. When the electron decays from E2 all the way to G, this large change in energy causes a photon with a shorter wavelength to be emitted (shorter than the photons involved in the excitation).

only certain lanthanides possess the proper characteristics for this mechanism to occur (Ho3+, Er3+, Nd3+, and Tm3+) when commercially-available diode lasers are used (which usually have incident wavelengths of around 975 or 808 nm). The relevant energy levels are called G, E1, and E2 (for ground state, excited state 1, and excited state 2). Electrons in the E1 excited state have long lifetimes before they return to the ground state G. As such, after an electron is excited to E1, it remains there for long enough that it can be promoted to E2 by another photon. When the electron decays from E2 all the way to G, this large change in energy causes a photon with a shorter wavelength to be emitted (shorter than the photons involved in the excitation). excited to E1 and then to E2. When the electron decays from E2 all the way to G, this large change in energy again causes a photon with a shorter wavelength to be emitted. Some of the most efficient UCNPs used for biomedical purposes operate by energy transfer upconversion and involve sensitizer/activator ion pairs of Yb3+/Tm3+, Yb3+/Er3+, or Yb3+/Ho3+ with excitation wavelengths of about 975 nm. The Yb3+ ion does not have an E2 energy level, it can only be excited from G to E1. This makes the upconversion process more efficient since the two energy levels of Yb3+ cannot cause cross-relaxations (a phenomenon which has a deleterious effect on upconversion). In addition to Yb3+-based UCNPs that work by energy transfer upconverion, some single-lanthanide UCNPs have also been developed. In these, the single type of lanthanide ion acts as a sensitizer and an activator.

excited to E1 and then to E2. When the electron decays from E2 all the way to G, this large change in energy again causes a photon with a shorter wavelength to be emitted. Some of the most efficient UCNPs used for biomedical purposes operate by energy transfer upconversion and involve sensitizer/activator ion pairs of Yb3+/Tm3+, Yb3+/Er3+, or Yb3+/Ho3+ with excitation wavelengths of about 975 nm. The Yb3+ ion does not have an E2 energy level, it can only be excited from G to E1. This makes the upconversion process more efficient since the two energy levels of Yb3+ cannot cause cross-relaxations (a phenomenon which has a deleterious effect on upconversion). In addition to Yb3+-based UCNPs that work by energy transfer upconverion, some single-lanthanide UCNPs have also been developed. In these, the single type of lanthanide ion acts as a sensitizer and an activator. transfer energy to a third ion (which can be of a different type) and excite the third ion to its own E1 state. In this case, the E1 state of the third ion is twice as energetic as the E1 states of the other two ions. When the third ion returns to its ground state, it releases a photon with a shorter wavelength than the incident photons. Cooperative sensitization upconversion is much less efficient than the other mechanisms, but it may have some advantages for high-resolution imaging applications. The cooperative sensitization mechanism has been reported to occur with Yb3+/Tb3+, Yb3+/Eu3+, and Yb3+/Pr3+ ion pairs.

transfer energy to a third ion (which can be of a different type) and excite the third ion to its own E1 state. In this case, the E1 state of the third ion is twice as energetic as the E1 states of the other two ions. When the third ion returns to its ground state, it releases a photon with a shorter wavelength than the incident photons. Cooperative sensitization upconversion is much less efficient than the other mechanisms, but it may have some advantages for high-resolution imaging applications. The cooperative sensitization mechanism has been reported to occur with Yb3+/Tb3+, Yb3+/Eu3+, and Yb3+/Pr3+ ion pairs. ion-ion interactions, so it is closely associated with dopant ion concentration. It can cause quenching at high concentrations, but tuning ion concentrations allows modulation of emitted light colors via other mechanisms. Note that cross relaxation on its own does not cause upconversion, but that it can influence upconversion events as other steps occur.

ion-ion interactions, so it is closely associated with dopant ion concentration. It can cause quenching at high concentrations, but tuning ion concentrations allows modulation of emitted light colors via other mechanisms. Note that cross relaxation on its own does not cause upconversion, but that it can influence upconversion events as other steps occur. energy to a second ion, its electron goes down to E1, and the second ion’s electron is excited from G to E1 by cross relaxation. Last, the second ion transfers its energy to a third ion, resulting in two ions at the E1 state by the end of the loop. In this way, more and more ions are excited to the E1 state as the loop repeats (two, four, eight, etc.) Some of the ions in the E2 state (from the first step) will decay to G, causing upconverted photons to be released.

energy to a second ion, its electron goes down to E1, and the second ion’s electron is excited from G to E1 by cross relaxation. Last, the second ion transfers its energy to a third ion, resulting in two ions at the E1 state by the end of the loop. In this way, more and more ions are excited to the E1 state as the loop repeats (two, four, eight, etc.) Some of the ions in the E2 state (from the first step) will decay to G, causing upconverted photons to be released.

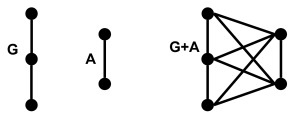

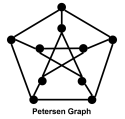

with a vertex set V(G)∪V(A) and an edge set V(G)∪V(A).

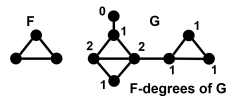

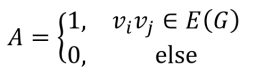

with a vertex set V(G)∪V(A) and an edge set V(G)∪V(A). the vertices of G and A to be labeled in a sequential manner (i.e. V(G)={g1,g2,…,gn} and V(A)={a1,a2,…,am}) so that equivalences between vertices can be decided. In addition, the Cartesian product of graphs is commutative, that is G⨯A=A⨯G.

the vertices of G and A to be labeled in a sequential manner (i.e. V(G)={g1,g2,…,gn} and V(A)={a1,a2,…,am}) so that equivalences between vertices can be decided. In addition, the Cartesian product of graphs is commutative, that is G⨯A=A⨯G.

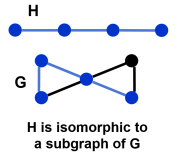

the vertices of H and G, the labeled graph H is isomorphic to a subgraph of the labeled graph G.

the vertices of H and G, the labeled graph H is isomorphic to a subgraph of the labeled graph G. constructed. The resulting graph is a minimum spanning tree of G.

constructed. The resulting graph is a minimum spanning tree of G.

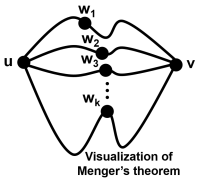

path for every pair of vertices u,v∈D. An orientation which converts a simple graph into a strongly connected digraph is called a strong orientation. Alternatively, a strongly connected digraph is a digraph for which every vertex can be visited by a single directed path.

path for every pair of vertices u,v∈D. An orientation which converts a simple graph into a strongly connected digraph is called a strong orientation. Alternatively, a strongly connected digraph is a digraph for which every vertex can be visited by a single directed path.