Click here for a PDF version of the virus zoo

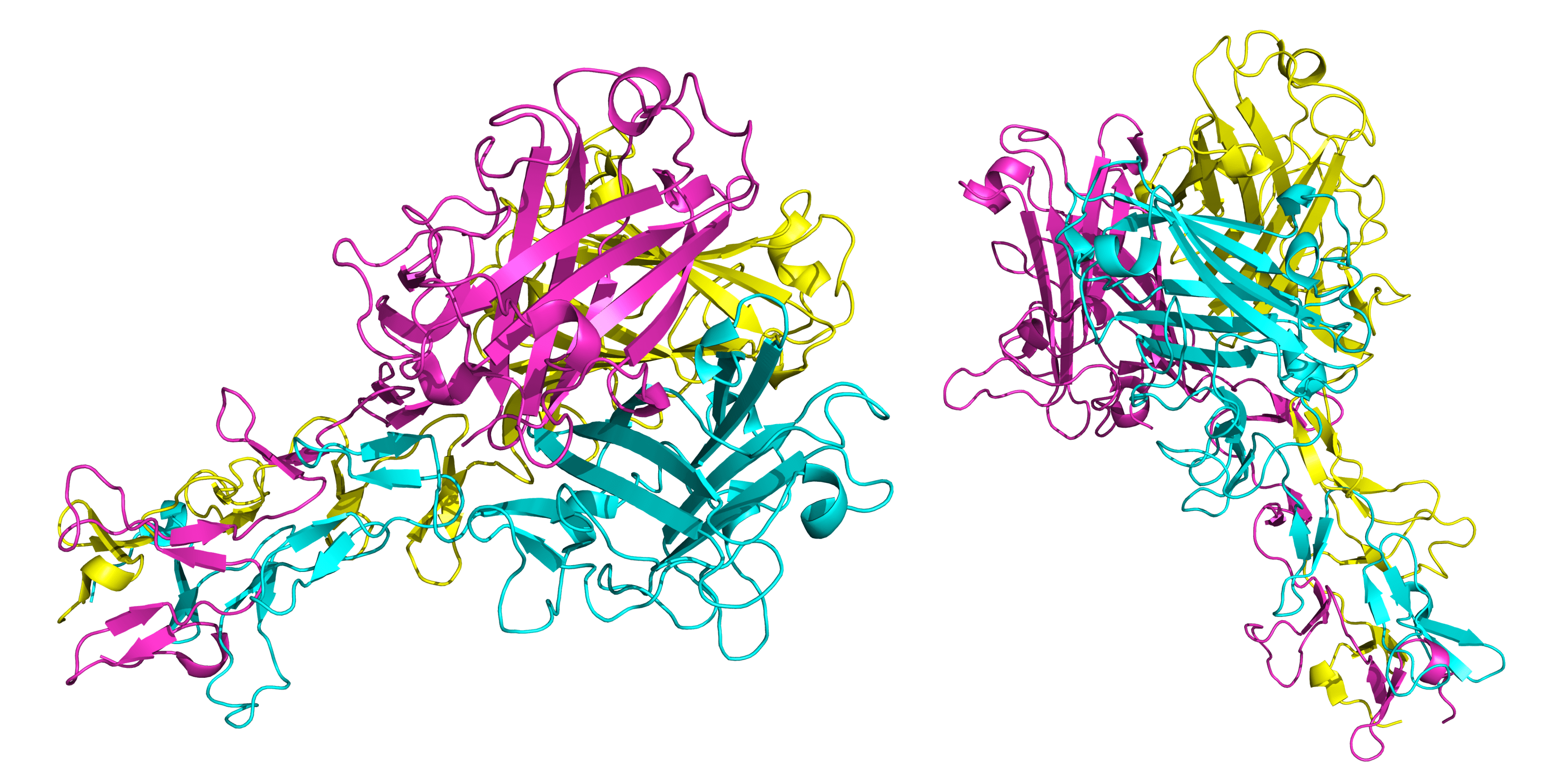

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)

Genome and Structure:

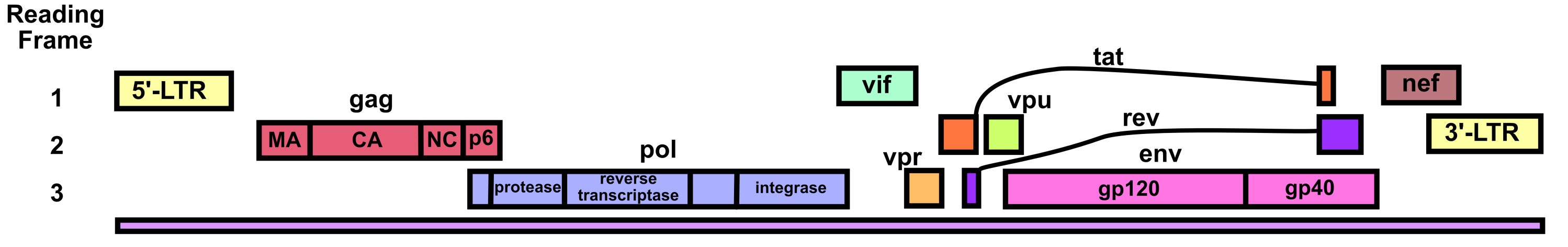

HIV’s genome is a 9.7 kb linear positive-sense ssRNA.1 There is a m7G-cap (specifically the standard eukaryotic m7GpppG as added by the host’s enzymes) at the 5’ end of the genome and a poly-A tail at the 3’ end of the genome.2 The genome also has a 5’-LTR and 3’-LTR (long terminal repeats) that aid its integration into the host genome after reverse transcription, that facilitate HIV genetic regulation, and that play a variety of other important functional roles. In particular, it should be noted that the integrated 5’UTR contains the HIV promoter called U3.3,4

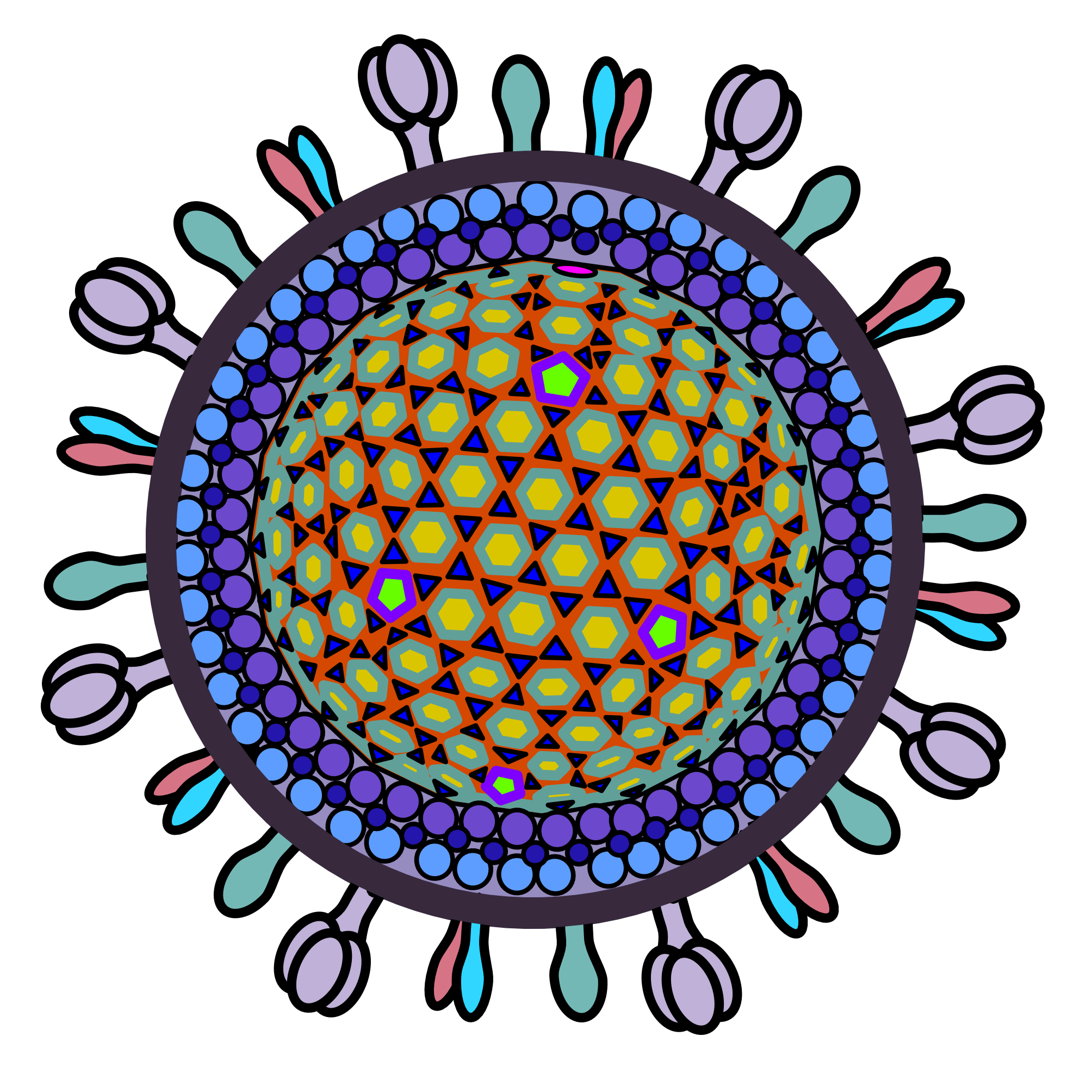

HIV’s genome translates three polyproteins (as well as several accessory proteins). The Gag polyprotein contains the HIV structural proteins. The Gag-Pol polyprotein contains (within its Pol component) the enzymes viral protease, reverse transcriptase, and integrase. The Gag-Pol polyprotein is produced via a –1 ribosomal frameshift at the end of Gag translation. Because of the lower efficiency of this frameshift, Gag-Pol is synthesized 20-fold less frequently than Gag.5 The frameshift’s mechanism depends upon a slippery heptanucleotide sequence UUUUUUA and a downstream RNA secondary structure called the frameshift stimulatory signal (FSS).6 This FSS controls the efficiency of the frameshift process.

The HIV RNA genome undergoes alternative splicing to produce the rest of the viral proteins. One splicing event produces an RNA that separately encodes the Vpu protein and the Env protein (also called gp160).6–8 A mechanism called ribosome shunting is used to transition from Vpu’s open reading frame to Env’s open reading frame. The Env protein contains the gp41 and gp120 proteins. Env is post-translationally cleaved into gp41 and gp120 by a host furin enzyme in the endoplasmic reticulum.9 It is important to note that Env is also heavily glycosylated post-translationally to help HIV evade the immune system. Several other complex splicing events lead to the production of RNAs encoding Tat, Rev, Nef, Vif, and Vpr.

HIV viral protease cleaves the Gag polyprotein and thus produces structural proteins including the capsid protein CA (also called p24), the matrix protein MA (also called p17), the nucleocapsid protein NC (also called p7), and the p6 peptide.10 The HIV core capsid is shaped like a truncated cone and consists of about 1500 CA monomers. Most of the CA proteins assemble into hexamers, but a few pentamers are present. The pentamers help give the core capsid its conical morphology by providing extra curvature near the top and bottom. Each core capsid contains two copies of the HIV genomic RNA, complexed with NC protein. Reverse transcriptase, integrase, and viral accessory proteins are also held within the core capsid. HIV’s core capsid is packaged into a lipid envelope that bears gp41-gp120 glycoprotein heterodimers. The MA protein forms a layer between the core capsid and the envelope.

Accessory proteins Vpu, Tat, Rev, Nef, Vif, and Vpr facilitate a variety of functions. Vpu induces degradation of CD4 proteins within the endoplasmic reticulum of host CD4+ T cells. It does this by using its cytosolic domain as a molecular adaptor between CD4 and a ubiquitin ligase (which subsequently triggers proteosomal degradation of the CD4).11 The reason that Vpu does this is to prevent HIV superinfection wherein two different types of HIV might infect the same cell and interfere with each other. This is an example of competition between viruses.12 Vpu also enhances release of HIV virions from infected cells by using its cytosolic domain to inhibit a host protein called tetherin (also known as BST-2).11 Without Vpu, tetherin would bind the viral envelope to the cell surface as well to other HIV virus particles, impeding release.

Tat, also called the viral transactivator protein, is necessary for efficient transcriptional elongation of the HIV genome after integration into the host DNA.13 Tat binds the viral transactivation response element (TAR), a structured RNA motif present at the beginning of the HIV transcripts. It then recruits protein positive transcription elongation factor b (P-TEFb). This allows P-TEFb to phosphorylate certain residues in the C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II, stimulating transcriptional elongation. Tat also recruits several of the host cell’s histone acetyltransferases to the viral 5’-LTR so as to open the chromatin around the U3 promoter and related parts of the integrated HIV genome.3,4 Finally, Tat is secreted from infected cells14 and acts as an autocrine and paracrine signaling molecule.4 It inhibits antigen-specific lymphocyte proliferation, stimulates expression of certain cytokines and cytokine receptors, modulates the activities of various host cell types, causes neurotoxicity in the brain, and more.

Rev facilitates nuclear export of the unspliced and singly spliced HIV RNAs by binding to a sequence located in the Env coding region called the Rev response element (RRE).13 The Rev protein forms a dimer upon binding to the RRE and acts as an adaptor, binding a host nuclear export factor called CRM1. Rev is also known to form higher-order oligomers via cooperative multimerization of the RNA-bound dimers.

Nef is a myristoylated protein that downregulates certain host T cell proteins and thereby increases production of virus. Nef is localized to the cytosol and the plasma membrane. It specifically inhibits CD4, Lck, CTLA-4, and Bad.15 Downregulating CD4 contributes to the prevention of superinfection that also occurs with Vpu’s inhibition of CD4. Nef induces endocytosis of plasma membrane Lck protein and traffics it to recycling endosomes and the trans-Golgi network. At these intracellular compartments, Lck signals for Ras and Erk activation, which triggers IL-2 production. IL-2 causes T cells to grow and proliferate, leading to more T cells that HIV can infect and leading to activation of the machinery HIV needs to replicate itself within infected T cells. Nef triggers lysosomal degradation of CTLA-4. This is because CTLA-4 can serve as an off-switch for T cells, which would lead to inhibition of HIV replication if active. Nef inactivates the Bad protein via phosphorylation. Bad participates in apoptotic cascades, so Nef prevents apoptosis of the infected host cell in this way.

Vif forms a complex with the host antiviral proteins APOBEC3F and APOBEC3G and induces their ubiquitination and subsequent degradation by the proteosome.16 It also may inhibit these proteins through other mechanisms. APOBEC3F and APOBEC3G are cytidine deaminases that hypermutate the negative-sense strand of HIV cDNA, leading to weak or nonviable viruses.17 These proteins also interfere with reverse transcription by blocking tRNALys3 from binding to the HIV RNA 5’UTR (tRNALys3 usually acts as a primer to initiate reverse transcription of the HIV genome).18

Vpr facilitates nuclear import of the HIV pre-integration complex.19 The pre-integration complex consists of viral cDNA and associated proteins (uncoating and reverse transcription have already occurred at this stage). Vpr binds the pre-integration complex and recruits host importins to enable nuclear import. It may further enhance nuclear import through interactions with some of the nuclear pore proteins. In addition to nuclear import, Vpr has several more functions: it acts as a coactivator (along with other proteins) of the HIV 5’UTR’s U3 promoter, might influence NF-κB regulation, may modulate apoptotic pathways, and arrests the cell cycle at the G2 stage.

Life cycle:

CD4+ T cells represent the primary targets of HIV, though the virus is also capable of infecting other cell types such as dendritic cells.20 HIV infects CD4+ T cells through binding its gp120 glycoprotein to the CD4 receptor and the CCR5 coreceptor or the CXCR4 coreceptor.10 This triggers fusion of the viral envelope with the plasma membrane and allows the core capsid to enter the cytosol.

HIV’s core capsid is transported by motor proteins along microtubules to dock at nuclear pores. The nuclear pore complex has flexible cytosolic filaments composed primarily of the Nup358 protein, which interacts with the core capsid.21 These interactions guide the narrow end of the core capsid into the nuclear pore’s central channel. Next, the core capsid interacts with the central channel’s unstructured phenylalanine-glycine (FG) repeats that exist in a hydrogel-like liquid phase. As the core capsid translocates through the central pore, it binds the Nup153 protein, a component of the nuclear pore complex’s basket. Finally, many copies of the nucleoplasmic CPSF6 protein coat the core capsid and escort it towards its genomic site of integration. It is thought that the reverse transcription process begins inside of the core capsid at this point, leading to cDNA synthesis.21,22 Buildup of newly made cDNA within the core capsid likely results in pressure that helps rupture the capsid structure, facilitating uncoating.

Tetrameric HIV integrase binds both of the viral LTRs and facilitates integration of the cDNA into the host genome.23 Though integration sites vary widely, they are not entirely random. Host chromatin structure and other factors influence where the viral cDNA integrates.24 Transcription of HIV RNAs can then proceed from the U3 promoter with the aid of the Tat protein and host factors. As described earlier, a series of RNA splicing events produce the various RNAs necessary to synthesize all of the different HIV proteins and polyproteins.

Env protein is trafficked to the cell membrane through the secretory pathway. It is cleaved by a host furin enzyme into gp41 and gp160 components during its time in the endoplasmic reticulum.9 Gag and Gag-Pol polyproteins are expressed cytosolically. Since Gag is post-translationally modified by amino-terminal myristoylation, it anchors to the cell membrane by inserting its myristate tail into the lipid bilayer.25 Gag and a smaller number of Gag-Pol accumulate on the inner membrane surface and incorporate gp41-gp160 complexes. NC domains in the Gag proteins bind and help package the two copies of HIV genomic RNA. The p6 region of the Gag protein (located at the C-terminal end) then recruits host ESCRT-I and ALIX proteins, which subsequently sequester host ESCRT-III and VPS4 complexes to drive budding and membrane scission, releasing virus into the extracellular space. After this, the HIV viral protease (from within the Gag-Pol polyprotein) cleaves the Gag and Gag-Pol polyproteins into their constituent proteins, facilitating maturation of the released HIV particles.

SARS-CoV-2

Genome and Structure:

The SARS-CoV-2 genome consists of about 30 kb of linear positive-sense ssRNA. There is a m7G-cap (specifically m7GpppA1) at the 5’ end of the genome and a 30-60 nucleotide poly-A tail at the 3’ end of the genome. These protective structures minimize exonuclease degradation.26 The genome also has a 5’ UTR and a 3’ UTR which contain sequences that aid in transcriptional regulation and in packaging. The SARS-CoV-2 genome directly translates two partially overlapping polyproteins, ORF1a and ORF1b. There is a –1 ribosomal frameshift in ORF1b relative to ORF1a. Within the polyproteins, two self-activating proteases (Papain-like protease PLpro and 3-chymotrypsin-like protease 3CLpro) perform cleavage events that lead to the generation of the virus’s 16 non-structural proteins (nsps). It should be noted that the 3CLpro is also known as the main protease or Mpro. The coronavirus also produces 4 structural proteins, but these are not translated until after the synthesis of corresponding subgenomic RNAs via the viral replication complex. To create these subgenomic RNAs, negative-sense RNA must first be made and then undergo conversion back to positive-sense RNA for translation. Genes encoding the structural proteins are located downstream of the ORF1b section.

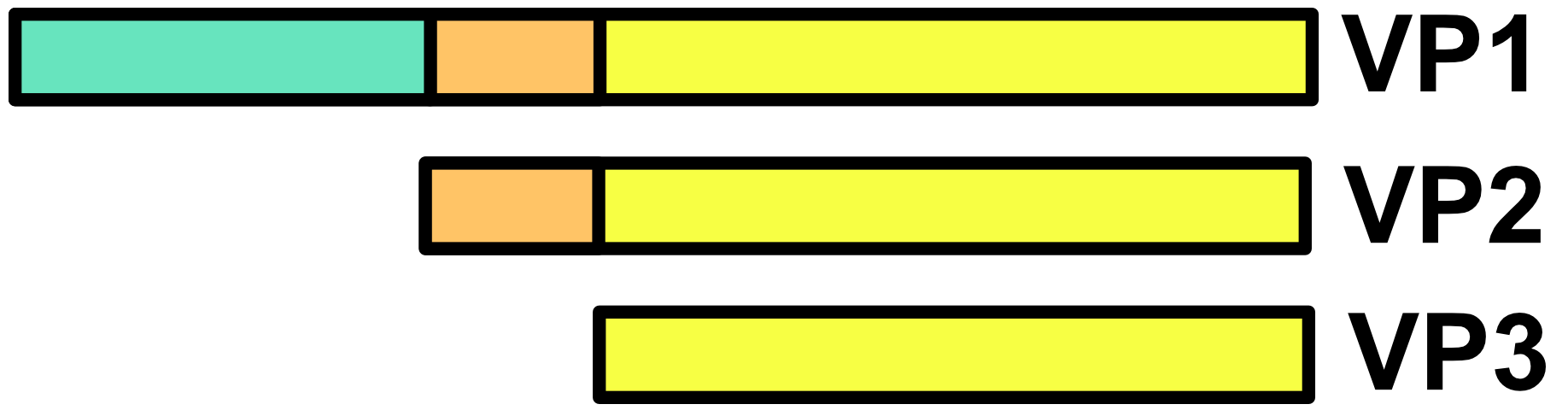

SARS-CoV-2’s four structural proteins include the N, E, M, and S proteins. Many copies of the N (nucleocapsid) protein bind the RNA genome and organize it into a helical ribonucelocapsid complex. The complex undergoes packaging into the viral envelope during coronavirus budding. Interactions between the N protein and the other structural proteins may facilitate this packaging process. The N protein also inhibits host immune responses by antagonizing viral suppressor RNAi and by blocking the signaling of interferon production pathways.27

The transmembrane E (envelope) protein forms pentamers and plays a key but poorly understood role in the budding of viral envelopes into the endoplasmic reticulum Golgi intermediate compartment (ERGIC).28–30 Despite its importance in budding, mature viral particles do not incorporate very many E proteins into their envelopes. One of the posttranslational modifications of the E protein is palmitoylation. This aids subcellular trafficking and interactions with membranes. E protein pentamers also act as ion channels that alter membrane potential.31,32 This may lead to inflammasome activation, a contributing factor to cytokine storm induction.

The M (membrane) protein is the most abundant protein in the virion and drives global curvature in the ERGIC membrane to facilitate budding.30,33 It forms transmembrane dimers that likely oligomerize to induce this curvature.34 The M protein also has a cytosolic (and later intravirion) globular domain that likely interacts with the other structural proteins. M protein dimers also induce local curvature through preferential interactions with phosphatidylserine and phosphatidylinositol lipids.29,30 M proteins help sequester S proteins into the envelopes of budding viruses.35

The S (spike) protein of SARS-CoV-2 has been heavily studied due to its central roles in the infectivity and immunogenicity of the coronavirus. It forms a homotrimer that protrudes from the viral envelope and is heavily glycosylated. It binds the host’s ACE2 receptor (angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptor) and undergoes conformational changes to promote viral fusion.36 The S protein undergoes cleavage into S1 and S2 subunits by the host’s furin protease during viral maturation.37,38 This enhances SARS-CoV-2 entry into lung cells and may partially explain the virus’s high degree of transmissibility. The S1 fragment contains the receptor binding domain (RBD) and associated machinery while the S2 fragment facilitates fusion. Prior to cellular infection, most S proteins exist in a closed prefusion conformation where the RBDs of each monomer are hidden most of the time.39 After the S protein binds ACE2 during transient exposure of one of its RBDs, the other two RBDs quickly bind as well. This binding triggers a conformational change in the S protein that loosens the structure, unleashing the S2 fusion component and exposing another proteolytic cleavage site called S2’. Host transmembrane proteases such as TMPRSS2 cut at S2’, causing the full activation of the S2 fusion subunit and the dramatic elongation of the S protein into the postfusion conformation. This results in the viral envelope fusing with the host membrane and uptake of the coronavirus’s RNA into the cell.

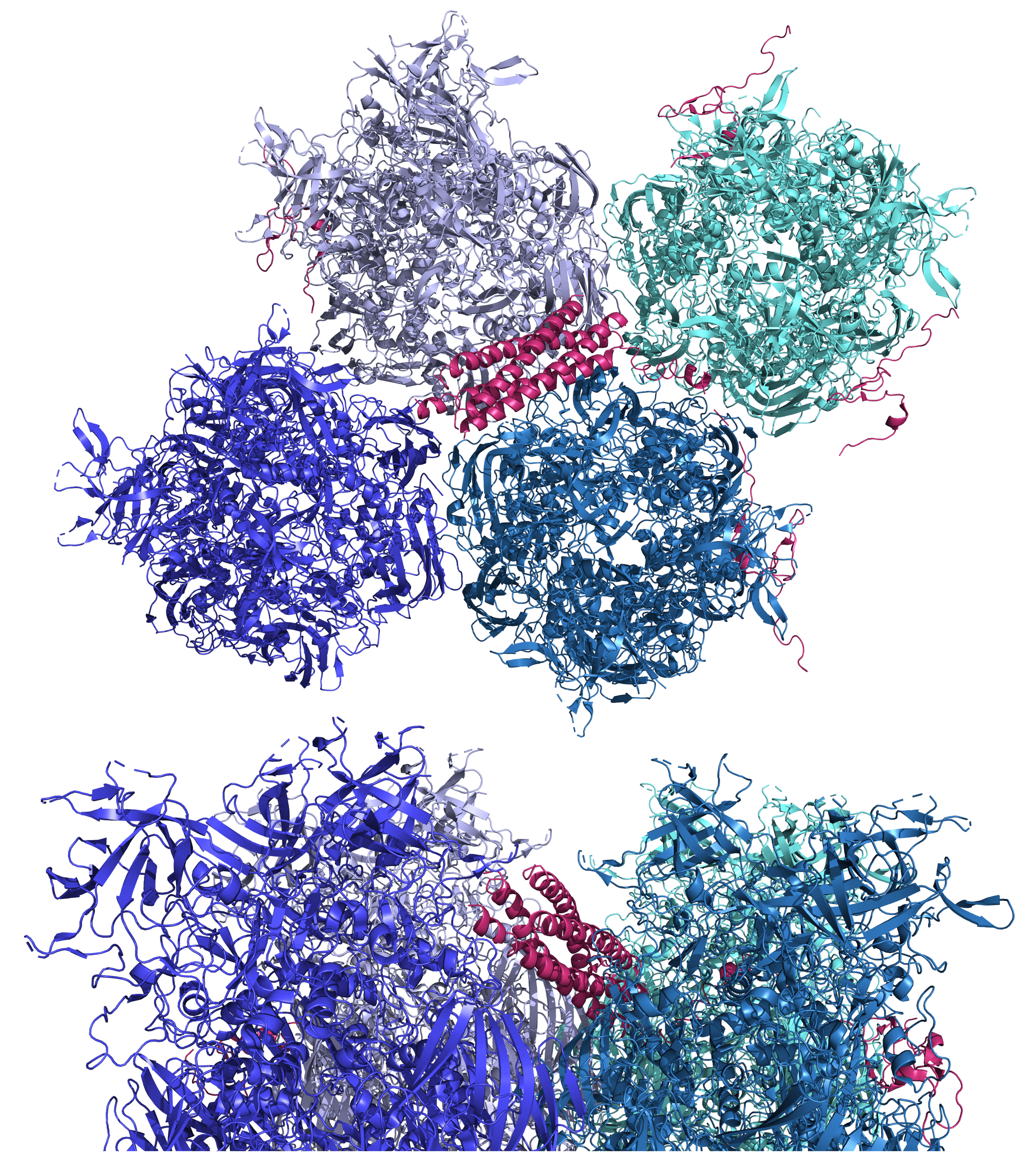

The 16 nsps of SARS-CoV-2 play a variety of roles. For instance, nsp1 shuts down host cell translation by plugging the mRNA entry channel of the ribosome, inhibiting the host cell’s immune responses and maximizing viral production.40,41 Viral proteins still undergo translation because a conserved sequence in the coronavirus RNA helps circumvent the blockage through a poorly understood mechanism. The nsp5 protein is the protease 3CLpro.42 The nsp3 protein contains several subcomponents, including the protease PLpro. The nsp12, nsp7, and nsp8 proteins come together to form the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) that replicates the viral genome.42,43 The nsp2 protein is likely a topoisomerase which functions in RNA replication. The nsp4 and nsp6 proteins as well as certain subcomponents of nsp3 restructure intracellular host membranes into double-membrane vesicles (DMVs) which compartmentalize viral replication.44

Beyond the 4 structural proteins and 16 nsps of SARS-CoV-2, the coronaviral genome also encodes some poorly understood accessory proteins including ORF3a, ORF3b, ORF6, ORF7a, ORF7b, ORF8 and ORF9b.45 These accessory proteins are non-essential for replication in vitro, but they are thought to be required for the virus’s full degree of virulence in vivo.

Life cycle:

As mentioned, SARS-CoV-2 infects cells by first binding a S protein RBD to the ACE2 receptor. This triggers a conformational change that elongates the S protein’s structure and reveals the S2 fusion fragment, facilitating fusion of the virion envelope with the host cell membrane.39 Cleavage of the S’ site by proteases like TMPRSS2 aid this change from the prefusion to postfusion configurations. Alternatively, SARS-CoV-2 can enter the cell by binding to ACE2, undergoing endocytosis, and fusing with the endosome to release its genome (as induced by endosomal cathepsin proteases).45 After release of the SARS-CoV-2 genome into the cytosol, the N protein disassociates and allows translation of ORF1a and ORF1b, producing polyproteins which are cleaved into mature proteins by the PLpro and 3CLpro proteases as discussed earlier.

The RdRp complex synthesizes negative-sense full genomic RNAs as well as negative-sense subgenomic RNAs. In the latter case, discontinuous transcription is employed, a process by which the RdRp jumps over certain sections of the RNA and initiates transcription separately from the rest of the genome.46 The negative-sense RNAs are subsequently converted back into positive-sense full genomic RNAs and positive-sense subgenomic RNAs. The subgenomic RNAs are translated to make structural proteins and some accessory proteins.45

As described earlier, the nsp4, nsp6, and parts of nsp3 proteins remodel host endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to create DMVs.45 These DMVs are the site of the coronaviral genomic replication and serve to shield the viral RNA and RdRp complex from cellular innate immune factors. DMVs cluster together and are continuous with the ER mostly through small tubular connections. After replication, the newly synthesized coronavirus RNAs undergo export into the cytosol through molecular pore complexes that span both membranes of the DMVs.47 These molecular pore complexes are composed of nsp3 domains and possibly other viral and/or host proteins.

Newly replicated SARS-CoV-2 genomic RNAs complex with N proteins to form helical nucleocapsids. To enable packaging, the nucleocapsids interact with M protein cytosolic domains which protrude at the ERGIC.48 M proteins, E proteins, and S proteins are all localized to the ERGIC membrane. The highly abundant M proteins induce curvature of the membrane to facilitate budding. As mentioned, E proteins also play essential roles in budding, but the mechanisms are poorly understood. Once the virions have budded into the ERGIC, they are shuttled through the Golgi via a series of vesicles and eventually secreted out of the cell.

Adeno-associated virus (AAV)

Genome and Structure:

AAV genomes are about 4.7 kb in length and are composed of ssDNA. Inverted terminal repeats (ITRs) form hairpin structures at ends of the genome. These ITR structures are important for AAV genomic packaging and replication. Rep genes (encoded via overlapping reading frames) include Rep78, Rep68, Rep52, Rep40.49 These proteins facilitate replication of the viral genome. As a Dependoparvovirus, additional helper functions from adenovirus (or certain other viruses) are needed for AAVs to replicate.

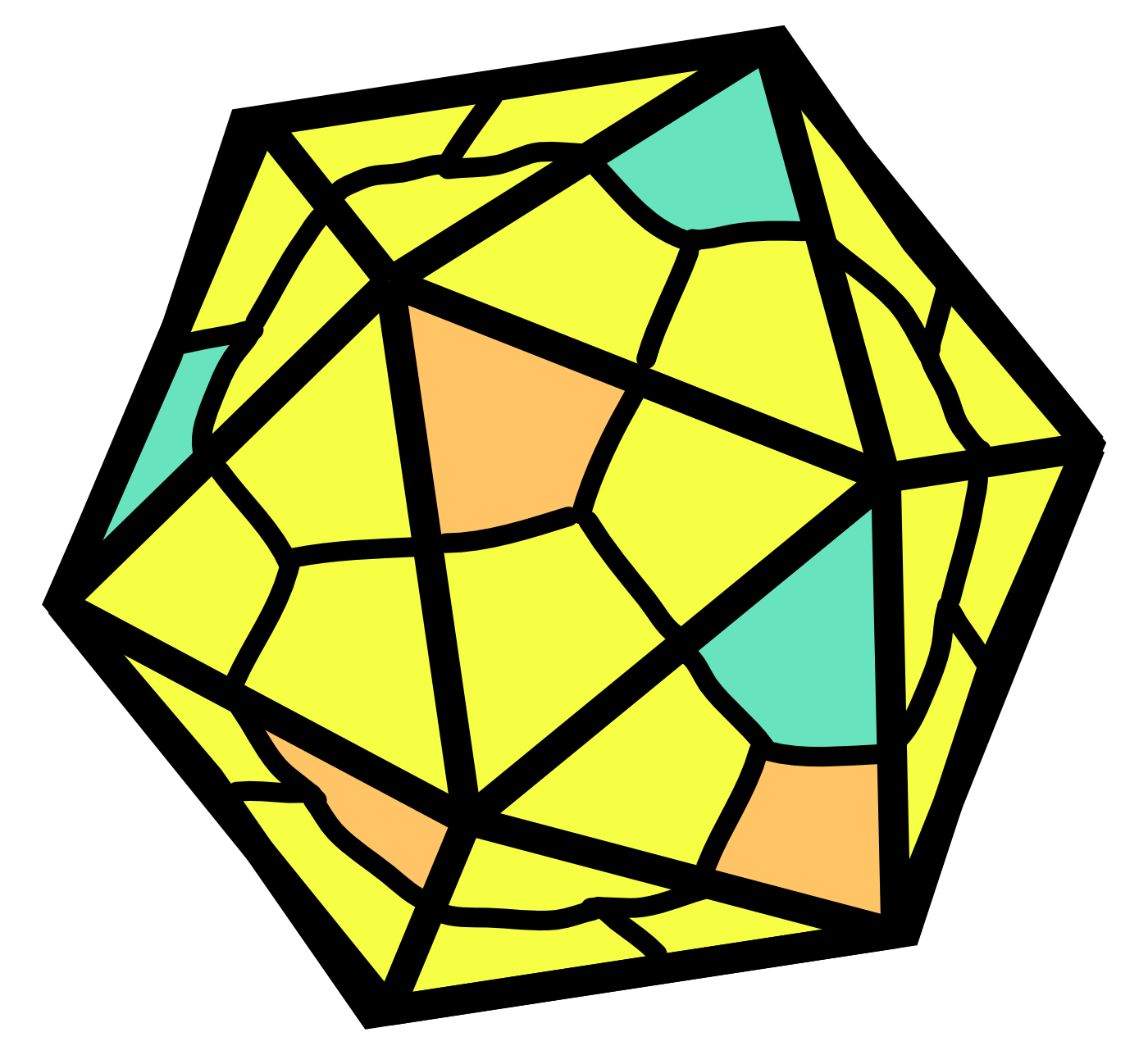

AAV capsids are about 25 nm in diameter. Cap genes include VP1, VP2, VP3 and are transcribed from overlapping reading frames.50 The VP3 protein is the smallest capsid protein. The VP2 protein is the same as VP3 except that it includes an N-terminal extension with a nuclear localization sequence. The VP1 protein is the same as VP2 except that it includes a further N-terminal extension encoding a phospholipase A2 (PLA2) that facilitates endosomal escape during infection. In the AAV capsid, VP1, VP2, and VP3 are present at a ratio of roughly 1:1:10. It should be noted that this ratio is actually the average of a distribution, not a fixed number.

Frame-shifted start codons in the Cap gene region transcribe AAP (assembly activating protein) and MAAP (membrane associated accessory protein). These proteins help facilitate packaging and other aspects of the AAV life cycle.

Life cycle:

There are a variety of different AAV serotypes (AAV2, AAV6, AAV9, etc.) that selectively infect certain tissue types. AAVs bind to host cell receptors and are internalized by endocytosis. The particular receptors involved can vary depending on the AAV serotype, though some receptors are consistent across many serotypes. Internalization occurs most often via clathrin-coated pits, but some AAVs are internalized by other routes such as macropinocytosis or the CLIC/GEEC tubulovesicular pathway.51

After endocytosis, conformational changes in the AAV capsid lead to exposure of the PLA2 VP1 domain, which facilitates endosomal escape. The AAV is then transported to the nucleus mainly by motor proteins on cytoskeletal highways. It enters via nuclear pores and finishes uncoating its genome.

AAV genomes initiate replication using the ends of their ITR hairpins as primers. This leads to a series of complex steps involving strand displacement and nicking.49 In the end, new copies of the AAV genome are synthesized. The Rep proteins are key players in this process. It is important to realize that AAVs can only replicate in cells which have also been infected by adenovirus or similar helper viruses (this is why they are called “adeno-associated viruses”). Adenoviruses provide helper genes encoding proteins (e.g. E4, E2a, VA) that are vital for the successful completion of the AAV life cycle. After new AAV capsids have assembled from VP1, VP2, and VP3 and once AAV genomes have been replicated, the ssDNA genomes are threaded into the capsids via pores at their five-fold vertices.

AAVs are nonpathogenic, though a large fraction of people possess antibodies against at least some serotypes, so exposure to them is fairly common.

Adenovirus

Genome and Structure:

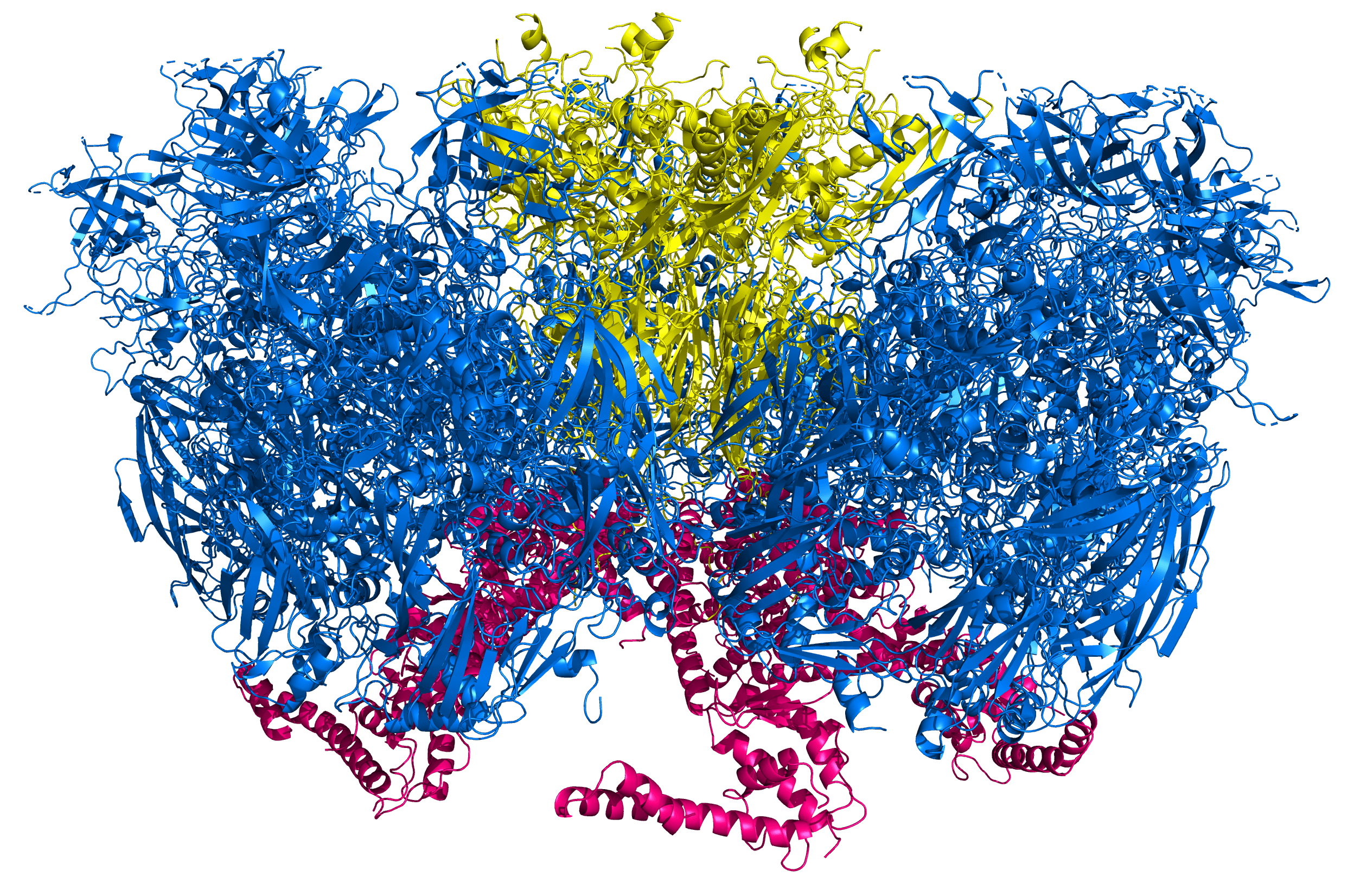

Adenovirus genomes are about 36 kb in size and are composed of linear dsDNA. They possess inverted terminal repeats (ITRs) which help facilitate replication and other functions. These genomes contain a variety of transcriptional units which are expressed at different times during the virus’s life cycle.52 E1A, E1B, E2A, E2B, E3, and E4 transcriptional units are expressed early during cellular infection. Their proteins are involved in DNA replication, transcriptional regulation, and suppression of host immune responses. The L1, L2, L3, L4, and L5 transcriptional units are expressed later in the life cycle. Their products include most of the capsid proteins as well as other proteins involved in packaging and assembly. Each transcriptional unit can produce multiple mRNAs through the host’s alternative splicing machinery.

The capsid of the adenovirus is about 90 nm in diameter and consists of three major proteins (hexon, penton, and fiber proteins) as well as a variety of minor proteins and core proteins. Hexon trimer is the most abundant protein in the capsid, the pentameric pentons occur at the vertices, and trimeric fibers are positioned on top of the pentons.53 The fibers point outwards from the capsid and end in knob domains which bind to cellular receptors. In Ad5, a commonly studied type of adenovirus, the fiber knob primarily binds to the coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor (CAR). That said, it should be noted that Ad5’s fiber knob can also bind to alternative receptors such as vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 and heparan sulfate proteoglycans.

Minor capsid proteins include pIX, pIIIa, pVI, and pVIII. The pIX protein interlaces between hexons and helps stabilize the capsid. Though pIX is positioned in the crevices between the hexons, it is still exposed to the outside environment. By contrast, the pIIIa, pVI, and pVIII proteins bind to the inside of the capsid and contribute further structural stabilization. When the adenovirus is inside of the acidic endosome during infection, conformational changes in the capsid release the pVI protein, which facilitates endosomal escape through membrane lytic activity.

Adenovirus core proteins include pV, pVII, protein μ (also known as pX), adenovirus proteinase (AVP), pIVa2, and terminal protein (TP).54 The pVII protein has many positively-charged arginine residues and so functions to condense the viral DNA. The pV protein bridges the core with the capsid through interactions with pVII and with pVI. AVP cleaves various adenoviral proteins (pIIIa, TP, pVI, pVII, pVIII, pX) to convert them to their mature forms.55 The pIVa2 and pX proteins interact with the viral DNA and may play roles in packaging or replication. TP binds to the ends of the genome and is essential for localizing the viral DNA in the nucleus and for viral replication.

Life Cycle:

Adenovirus infects cells by binding its fiber knob to cellular receptors such as CAR (in the case of Ad5). The penton then binds certain αv integrins, positioning the viral capsid for endocytosis.56 When the endosome acidifies, the adenovirus capsid partially disassembles, fibers and pentons fall away, and pVI is released.57 The pVI protein’s membrane lytic activity facilitates endosomal escape. Partially disassembled capsids then undergo dynein-mediated transport along microtubules and dock at the entrance to nuclear pores. The capsids further disassemble and releases DNA through the nuclear pore. This DNA remains complexed with pVII after it enters the nucleus.

Adenoviral transcription is initiated by the E1A protein, inducing expression of early genes.58 This subsequently leads to expression of the E2, E3, and E4 transcriptional units, which help the virus escape immune responses. This cascade leads to expression of the L1, L2, L3, L4, and L5 transcriptional units, which mainly synthesize viral structural proteins and facilitate capsid assembly.

In the nucleus, adenovirus genomes replicate within dense complexes of protein that can be seen as spots via fluorescence microscopy. Replication begins at the ITRs and is primed by TP.59 Several more viral proteins and host proteins also aid the initiation of replication. Nontemplate strands are displaced during replication but may reanneal and act as template strands later. Adenovirus DNA binding protein and adenovirus DNA polymerase play important roles in replication. Once the genome has been replicated, TP undergoes cleavage into its mature form, signaling for packaging of new genomes.

The adenoviral capsid assembly and maturation process occurs in the nucleus.58 Once enough assembled adenoviruses have accumulated, they rupture the nuclear membrane using adenoviral death protein and subsequently lyse the cell, releasing adenoviral particles.

Herpes Simplex Virus 1 (HSV-1)

Genome and Structure:

HSV-1 genomes are about 150 kb in size and are composed of linear dsDNA. These genomes include a unique long (UL) region and a unique short (US) region.60 The UL and US regions are both flanked by their own inverted repeats. The terminal inverted repeats are called TRL and TRS while the internal inverted repeats are called IRL and IRS. HSV-1 contains approximately 80 genes, though the complexity of its genomic organization makes an exact number of genes difficult to obtain. As with many other viruses, HSV-1 genomes encode early, middle, and late genes. The early genes activate and regulate transcription of the middle and late genes. Middle genes facilitate genome replication and late genes mostly encode structural proteins.

The diameter of HSV-1 ranges around 155 nm to 240 nm.61 Its virions include an inner icosahedral capsid (with a 125 nm diameter) surrounded by tegument proteins which are in turn enveloped by a lipid membrane containing glycoproteins.

HSV-1’s icosahedral capsid consists of a variety of proteins. Some of the most important capsid proteins are encoded by the UL19, UL18, UL38, UL6, UL17, and UL25 genes.62 The UL19 gene encodes the major capsid protein VP5, which forms pentamers and hexamers for the capsid. These VP5 pentamers and hexamers are glued together by triplexes consisting of two copies of VP23 (encoded by UL18) and one copy of VP19C (encoded by UL38).63 The UL6 gene encodes the protein that makes up the portal complex, a structure used by HSV-1 to release its DNA during infection. Each HSV-1 capsid has a single portal (composed of 12 copies of the portal protein) located at one of the vertices. UL17 and UL25 encode additional structural proteins that stabilize the capsid by binding on top of the other vertices. These two proteins also serve as a bridge between the capsid core and the tegument proteins.

The tegument of HSV-1 contains dozens of distinct proteins. Some examples include pUL36, pUL37, pUL7, and pUL51 proteins. The major tegument proteins are pUL36 and pUL37. The pUL36 protein binds on top of the UL17-UL25 complexes at the capsid’s vertices.64 The pUL37 protein subsequently associates with pUL36. The pUL51 protein associates with cytoplasmic membranes in infected cells and recruits the pUL7 protein.65 This pUL51-pUL7 interaction is important for HSV-1 assembly. HSV-1 has many more tegument proteins which play various functional roles.

HSV-1’s envelope contains up to 16 unique glycoproteins. Four of these glycoproteins (gB, gD, gH, and gL) are essential for viral entry into cells.66 The gD glycoprotein first binds to one of its cellular receptors (nectin-1, herpesvirus entry mediator or HVEM, or 3-O-sulfated heparan sulfate). This binding event triggers a conformational change in gD that allows it to activate the gH/gL heterodimer. Next, gH/gL activate gB which induces fusion of HSV-1’s envelope with the cell membrane. Though the remaining 12 envelope glycoproteins are poorly understood, it is thought that they also play roles that influence cellular tropism and entry.

Life cycle:

After binding to cellular receptors via its glycoproteins, HSV-1 induces fusion of its envelope with the host cell membrane.67 The capsid is trafficked to nuclear pores via microtubules. Since the capsid is too large to pass through a nuclear pore directly, the virus instead ejects its DNA through the pore via the portal complex.68

HSV-1 replicates its genome and assembles its capsids in the nucleus. But the assembled capsids are again too large to exist the nucleus through nuclear pores. To overcome this issue, HSV-1 first buds via the inner nuclear membrane into the perinuclear cleft (the space between nuclear membranes), acquiring a primary envelope.67 This process is driven by a pair of proteins (pUL34 and pUL31) which together form the nuclear egress complex. Next, the primary envelope fuses with the outer nuclear membrane, releasing the assembled capsids into the cytosol.

To acquire its final envelope, the HSV-1 capsid likely buds into the trans-Golgi network or into certain tubular vesicular organelles.69 These membrane sources contain the envelope proteins of the virus as produced by transcription and various secretory pathways. One player is the pUL51 tegument protein that starts associated with the membrane into which the virus buds. The interaction between pUL51 and pUL7 helps facilitate recruitment of the capsid to the membrane. (Capsid envelopment is also coupled in many other ways to formation of the outer tegument). The enveloped virion eventually undergoes trafficking through the secretory system and eventually is packaged into exosomes that fuse with the cell membrane and release completed virions into the extracellular environment.

In humans, HSV-1 infects the epithelial cells first and produces viral particles.70 It subsequently enters the termini of sensory neurons, undergoes retrograde transport into the brain, and remains in the central nervous system in a dormant state. During periods of stress in the host, the virus is reactivated and undergoes anterograde transport to infect epithelial cells once again.

References

1. Wain-Hobson, S., Sonigo, P., Danos, O., Cole, S. & Alizon, M. Nucleotide sequence of the AIDS virus, LAV. Cell 40, 9–17 (1985).

2. Wilusz, J. Putting an ‘End’ to HIV mRNAs: capping and polyadenylation as potential therapeutic targets. AIDS Res. Ther. 10, 31 (2013).

3. Marcello, A., Zoppé, M. & Giacca, M. Multiple Modes of Transcriptional Regulation by the HIV-1 Tat Transactivator. IUBMB Life 51, 175–181 (2001).

4. Brigati, C., Giacca, M., Noonan, D. M. & Albini, A. HIV Tat, its TARgets and the control of viral gene expression. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 220, 57–65 (2003).

5. Harrison, J. J. E. K. et al. Cryo-EM structure of the HIV-1 Pol polyprotein provides insights into virion maturation. Sci. Adv. 8, eabn9874 (2022).

6. Guerrero, S. et al. HIV-1 Replication and the Cellular Eukaryotic Translation Apparatus. Viruses vol. 7 199–218 at https://doi.org/10.3390/v7010199 (2015).

7. Feinberg, M. B. & Greene, W. C. Molecular insights into human immunodeficiency virus type 1 pathogenesis. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 4, 466–474 (1992).

8. Sertznig, H., Hillebrand, F., Erkelenz, S., Schaal, H. & Widera, M. Behind the scenes of HIV-1 replication: Alternative splicing as the dependency factor on the quiet. Virology 516, 176–188 (2018).

9. Behrens, A.-J. & Crispin, M. Structural principles controlling HIV envelope glycosylation. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 44, 125–133 (2017).

10. Campbell, E. M. & Hope, T. J. HIV-1 capsid: the multifaceted key player in HIV-1 infection. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 13, 471–483 (2015).

11. Andrew, A. & Strebel, K. HIV-1 Vpu targets cell surface markers CD4 and BST-2 through distinct mechanisms. Mol. Aspects Med. 31, 407–417 (2010).

12. Bour, S., Geleziunas, R. & Wainberg, M. A. The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) CD4 receptor and its central role in promotion of HIV-1 infection. Microbiol. Rev. 59, 63–93 (1995).

13. Engelman, A. & Cherepanov, P. The structural biology of HIV-1: mechanistic and therapeutic insights. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 10, 279–290 (2012).

14. Marino, J., Wigdahl, B. & Nonnemacher, M. R. Extracellular HIV-1 Tat Mediates Increased Glutamate in the CNS Leading to Onset of Senescence and Progression of HAND . Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience vol. 12 at https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnagi.2020.00168 (2020).

15. Abraham, L. & Fackler, O. T. HIV-1 Nef: a multifaceted modulator of T cell receptor signaling. Cell Commun. Signal. 10, 39 (2012).

16. Mehle, A. et al. Vif Overcomes the Innate Antiviral Activity of APOBEC3G by Promoting Its Degradation in the Ubiquitin-Proteasome Pathway *. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 7792–7798 (2004).

17. Donahue, J. P., Vetter, M. L., Mukhtar, N. A. & D’Aquila, R. T. The HIV-1 Vif PPLP motif is necessary for human APOBEC3G binding and degradation. Virology 377, 49–53 (2008).

18. Fei, G., Shan, C., Meijuan, N., Jenan, S. & Lawrence, K. Inhibition of tRNALys3-Primed Reverse Transcription by Human APOBEC3G during Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Replication. J. Virol. 80, 11710–11722 (2006).

19. Kogan, M. & Rappaport, J. HIV-1 Accessory Protein Vpr: Relevance in the pathogenesis of HIV and potential for therapeutic intervention. Retrovirology 8, 25 (2011).

20. Hladik, F. & McElrath, M. J. Setting the stage: host invasion by HIV. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8, 447–457 (2008).

21. Müller, T. G., Zila, V., Müller, B. & Kräusslich, H.-G. Nuclear Capsid Uncoating and Reverse Transcription of HIV-1. Annu. Rev. Virol. 9, 261–284 (2022).

22. Müller, T. G. et al. HIV-1 uncoating by release of viral cDNA from capsid-like structures in the nucleus of infected cells. Elife 10, e64776 (2021).

23. Marchand, C., Johnson, A. A., Semenova, E. & Pommier, Y. Mechanisms and inhibition of HIV integration. Drug Discov. Today Dis. Mech. 3, 253–260 (2006).

24. Hughes, S. H. & Coffin, J. M. What Integration Sites Tell Us about HIV Persistence. Cell Host Microbe 19, 588–598 (2016).

25. Freed, E. O. HIV-1 assembly, release and maturation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 13, 484–496 (2015).

26. Brant, A. C., Tian, W., Majerciak, V., Yang, W. & Zheng, Z.-M. SARS-CoV-2: from its discovery to genome structure, transcription, and replication. Cell Biosci. 11, 136 (2021).

27. Bai, Z., Cao, Y., Liu, W. & Li, J. The SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid Protein and Its Role in Viral Structure, Biological Functions, and a Potential Target for Drug or Vaccine Mitigation. Viruses vol. 13 at https://doi.org/10.3390/v13061115 (2021).

28. Schoeman, D. & Fielding, B. C. Coronavirus envelope protein: current knowledge. Virol. J. 16, 69 (2019).

29. Monje-Galvan, V. & Voth, G. A. Molecular interactions of the M and E integral membrane proteins of SARS-CoV-2. Faraday Discuss. (2021) doi:10.1039/D1FD00031D.

30. Collins, L. T. et al. Elucidation of SARS-CoV-2 budding mechanisms through molecular dynamics simulations of M and E protein complexes. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 12, 12249–12255 (2021).

31. Arya, R. et al. Structural insights into SARS-CoV-2 proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 433, 166725 (2021).

32. Yang, H. & Rao, Z. Structural biology of SARS-CoV-2 and implications for therapeutic development. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 19, 685–700 (2021).

33. J Alsaadi, E. A. & Jones, I. M. Membrane binding proteins of coronaviruses. Future Virol. 14, 275–286 (2019).

34. Neuman, B. W. et al. A structural analysis of M protein in coronavirus assembly and morphology. J. Struct. Biol. 174, 11–22 (2011).

35. Boson, B. et al. The SARS-CoV-2 envelope and membrane proteins modulate maturation and retention of the spike protein, allowing assembly of virus-like particles. J. Biol. Chem. 296, (2021).

36. Zhang, J., Xiao, T., Cai, Y. & Chen, B. Structure of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Curr. Opin. Virol. 50, 173–182 (2021).

37. Walls, A. C. et al. Structure, Function, and Antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Glycoprotein. Cell 181, 281-292.e6 (2020).

38. Peacock, T. P. et al. The furin cleavage site in the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein is required for transmission in ferrets. Nat. Microbiol. 6, 899–909 (2021).

39. Fertig, T. E. et al. The atomic portrait of SARS-CoV-2 as captured by cryo-electron microscopy. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 26, 25–34 (2022).

40. Schubert, K. et al. SARS-CoV-2 Nsp1 binds the ribosomal mRNA channel to inhibit translation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 27, 959–966 (2020).

41. Yuan, S. et al. Nonstructural Protein 1 of SARS-CoV-2 Is a Potent Pathogenicity Factor Redirecting Host Protein Synthesis Machinery toward Viral RNA. Mol. Cell 80, 1055-1066.e6 (2020).

42. Raj, R. Analysis of non-structural proteins, NSPs of SARS-CoV-2 as targets for computational drug designing. Biochem. Biophys. Reports 25, 100847 (2021).

43. Kirchdoerfer, R. N. & Ward, A. B. Structure of the SARS-CoV nsp12 polymerase bound to nsp7 and nsp8 co-factors. Nat. Commun. 10, 2342 (2019).

44. Roingeard, P. et al. The double-membrane vesicle (DMV): a virus-induced organelle dedicated to the replication of SARS-CoV-2 and other positive-sense single-stranded RNA viruses. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 79, 425 (2022).

45. Baggen, J., Vanstreels, E., Jansen, S. & Daelemans, D. Cellular host factors for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat. Microbiol. 6, 1219–1232 (2021).

46. Sashittal, P., Zhang, C., Peng, J. & El-Kebir, M. Jumper enables discontinuous transcript assembly in coronaviruses. Nat. Commun. 12, 6728 (2021).

47. Wolff, G. et al. A molecular pore spans the double membrane of the coronavirus replication organelle. Science (80-. ). 369, 1395–1398 (2020).

48. David, B. & Delphine, M. Betacoronavirus Assembly: Clues and Perspectives for Elucidating SARS-CoV-2 Particle Formation and Egress. MBio 12, e02371-21 (2021).

49. Sha, S. et al. Cellular pathways of recombinant adeno-associated virus production for gene therapy. Biotechnol. Adv. 49, 107764 (2021).

50. Wang, D., Tai, P. W. L. & Gao, G. Adeno-associated virus vector as a platform for gene therapy delivery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 18, 358–378 (2019).

51. Riyad, J. M. & Weber, T. Intracellular trafficking of adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors: challenges and future directions. Gene Ther. 28, 683–696 (2021).

52. Ahi, Y. S. & Mittal, S. K. Components of Adenovirus Genome Packaging. Frontiers in Microbiology vol. 7 1503 at https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmicb.2016.01503 (2016).

53. Gallardo, J., Pérez-Illana, M., Martín-González, N. & San Martín, C. Adenovirus Structure: What Is New? International Journal of Molecular Sciences vol. 22 at https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22105240 (2021).

54. Kulanayake, S. & Tikoo, S. K. Adenovirus Core Proteins: Structure and Function. Viruses vol. 13 at https://doi.org/10.3390/v13030388 (2021).

55. Russell, W. C. & Kemp, G. D. Role of Adenovirus Structural Components in the Regulation of Adenovirus Infection BT – The Molecular Repertoire of Adenoviruses I: Virion Structure and Infection. in (eds. Doerfler, W. & Böhm, P.) 81–98 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 1995). doi:10.1007/978-3-642-79496-4_6.

56. R., N. G. & L., S. P. Role of αv Integrins in Adenovirus Cell Entry and Gene Delivery. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 63, 725–734 (1999).

57. Pied, N. & Wodrich, H. Imaging the adenovirus infection cycle. FEBS Lett. 593, 3419–3448 (2019).

58. Georgi, F. & Greber, U. F. The Adenovirus Death Protein – a small membrane protein controls cell lysis and disease. FEBS Lett. 594, 1861–1878 (2020).

59. Hoeben, R. C. & Uil, T. G. Adenovirus DNA Replication. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 5, (2013).

60. McGeoch, D. J., Rixon, F. J. & Davison, A. J. Topics in herpesvirus genomics and evolution. Virus Res. 117, 90–104 (2006).

61. Laine, R. F. et al. Structural analysis of herpes simplex virus by optical super-resolution imaging. Nat. Commun. 6, 5980 (2015).

62. Mettenleiter, T. C., Klupp, B. G. & Granzow, H. Herpesvirus assembly: a tale of two membranes. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 9, 423–429 (2006).

63. E., H. E. Up close with herpesviruses. Science (80-. ). 360, 34–35 (2018).

64. H., F. W. et al. The Large Tegument Protein pUL36 Is Essential for Formation of the Capsid Vertex-Specific Component at the Capsid-Tegument Interface of Herpes Simplex Virus 1. J. Virol. 89, 1502–1511 (2015).

65. J., R. R., Rachel, F. & M., L. R. The Herpes Simplex Virus 1 UL51 Protein Interacts with the UL7 Protein and Plays a Role in Its Recruitment into the Virion. J. Virol. 89, 3112–3122 (2015).

66. T., H. A., E., D. R., E., H. E. & Thomas, S. Contributions of the Four Essential Entry Glycoproteins to HSV-1 Tropism and the Selection of Entry Routes. MBio 12, e00143-21 (2021).

67. Zeev-Ben-Mordehai, T., Hagen, C. & Grünewald, K. A cool hybrid approach to the herpesvirus ‘life’ cycle. Curr. Opin. Virol. 5, 42–49 (2014).

68. Newcomb, W. W., Cockrell, S. K., Homa, F. L. & Brown, J. C. Polarized DNA Ejection from the Herpesvirus Capsid. J. Mol. Biol. 392, 885–894 (2009).

69. Ahmad, I. & Wilson, D. W. HSV-1 Cytoplasmic Envelopment and Egress. International Journal of Molecular Sciences vol. 21 at https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21175969 (2020).

70. Roizman, B. & Whitley, R. J. An Inquiry into the Molecular Basis of HSV Latency and Reactivation. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 67, 355–374 (2013).