This material was originally published in DUJS 17S.

The Potential of Brain Emulation

The human brain has been described as “the most complex object in the universe.” Its network of 86 billion neurons,1 84 billion glial cells, and over 150 trillion synapses2 may seem intractable. Nonetheless, efforts to comprehensively map, understand, and even computationally reproduce this structure are underway. The Human Brain Project (HBP) and its precursor, the Blue Brain Project, have spearheaded the brain simulation goal,3 along with two other notable organizations – the China Brain Project and the BRAIN Initiative.

Whole brain emulation (WBE), the computational simulation of the human brain with synaptic (or higher) resolution, would fundamentally change medicine, artificial intelligence, and neurotechnology. Modeling the brain with this level of detail could reveal new insights about the pathogenesis of mental illness.4 It would provide a virtual environment in which to conduct experiments, though researchers would need to develop guidelines regarding the ethics of these experiments, since such a construct may possess a form of consciousness. This virtual connectome could also vastly accelerate studies of human intelligence, leading to the possibility of implementing this new understanding of cognition in artificial intelligence and even developing intelligent machines. Brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) may also benefit from WBE since more precise neuronal codes for coding motor actions and sensory information could be uncovered. By studying WBEs, the “language” of the brain’s operations could be revealed and may give rise to a rich array of new advances. On a scale which parallels the space program and the Human Genome Project, neuroscience may be approaching a revolution.

Foundations of Computational Neuroscience

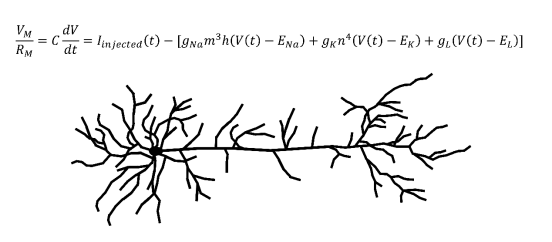

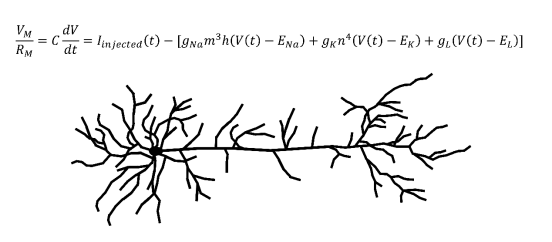

Biologically accurate neuronal simulations usually employ conductance-based models. The canonical conductance-based model developed by Alan Hodgkin and Andrew Huxley was published in 1952,5 and would win them the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Current models still use the core principles from the Hodgkin-Huxley model.6 This model is a differential equation which takes into account the conductances and equilibrium potentials of neuronal sodium channels, potassium channels, and channels that transport anions across the cell membrane.5 Conductance is defined as the inverse of electrical resistance and an equilibrium potential is the electrical potential energy across a membrane at equilibrium. The output of this equation is the total current across the membrane of the neuron, which can be converted to a voltage by multiplying by the total membrane resistance. The Hodgkin-Huxley equation can generate biologically accurate predictions for the membrane voltage of a neuron at a given time. Using these membrane voltages and the firing threshold of the neuron in question, the timing of action potentials can be computationally predicted, allowing neural activity to be simulated.

Another important concept in computational neuroscience is the multi-compartmental model. Consider an axon which synapses onto another neuron’s dendrite. When the axon terminal releases neurotransmitters which depolarize (move the membrane potential closer to zero) the other neuron’s dendritic membrane, the depolarization will need to travel down the dendrite, past the soma, and onto the axon of this post-synaptic neuron to contribute to the initiation of an action potential. Since the density of voltage-gated channels outside of the axon is relatively low, the depolarization decreases as it moves along this path. In order to accurately recreate a biological neuron in a computer, this process must also be modeled. To accomplish this, the model segments each portion of the neuronal membrane into multiple “compartments.” In general, increasing the number of compartments improves the accuracy of the model, but requires more computational power. Multi-compartmental models use more complicated partial differential equation extensions of the Hodkin-Huxley equation. When solved, the resulting multivariable functions uses both the location along the dendrite and the time to predict depolarization behavior, which is inputted to the postsynaptic virtual neuron.

These methods form the fundamentals for constructing simulated neurons and assemblies of neurons. They have shown remarkable biological fidelity even in complex simulations. Multi-compartmental Hodgkin-Huxley models, given the proper parameters from experimental data, can make predictive approximations of biological activity.

The Blue Brain Project

The quest to simulate the human brain has largely emerged from The Blue Brain Project, a collaboration headed by Henry Markram. In 2007, Markram announced the completion of the Blue Brain Project’s first phase, the detailed simulation of a rat neocortical column in IBM’s Blue Gene supercomputer. This achievement required a powerful engineering strategy that integrated the many components of the simulation.6 To start, gene expression data were used to determine ion channel distributions in the membranes of various types of cortical neuron. Over twenty different types of ion channel were considered in this analysis. These ion channels were incorporated into extensions of the Hodgkin-Huxley model. Three-dimensional neuron morphologies were paired with appropriate ion channel distributions and a database of virtual neuron subtypes was assembled. Experimental data on axon and dendrite locations was collected to recreate the synaptic connections in the neocortical column. A collision detection algorithm was employed to adjust the three-dimensional arrangement of axons and dendrites by “jittering” them until they matched the experimental data. This allowed the column’s structure to be reconstructed. Physiological recordings provided membrane conductances, probabilities of synaptic release, and other biophysical parameters necessary to model each neuronal subtype. In addition, plasticity rules mirroring those found in biological neurons were applied to the virtual neurons to allow them to perform learning. Parameters were optimized through a series of iterative tests and corrections.

By 2012, the project reached another milestone,7 the simulation of a larger brain structure known as a cortical mesocircuit that consisted of over 31,000 neurons in several hundred “minicolumns.” In this simulation, some of the details of synaptic connectivity were algorithmically predicted based on experimental data rather than strictly adhering to experimentally generated maps. Nevertheless, valuable insights were produced from the emulated mesocortical circuit. In vivo systems have shown puzzling bursts of uncorrelated activity. The simulation confirmed that this emergent property occurred as a consequence of destructive interference between excitatory and inhibitory signals. The simulation also demonstrated that, during moments of imbalance between these signals, choreographed patterns of neuronal encoding can occur within the “overspill.” Such observations in this virtual cortical circuit have increased understanding of the mechanisms of neural activity.

The Human Brain Project

As the Blue Brain Project developed, it was eventually rebranded as The Human Brain Project (HPB) to reflect its overarching goal. In 2013, the HBP was selected as a European Union Flagship project and granted over 1 billion euros in funding (equivalent to slightly more than 1 billion USD). Criticisms inevitably arose. Some scientists feared that it would divert funding from other areas of research.8 A major complaint was that the HBP was ignoring experimental neuroscience in favor of simulations. The simulation approach would need to be complemented by further data collection efforts since structural and functional mapping information is lacking. As a result, the HBP restructured to broaden its focus. An array of neuroscience platforms with varying levels of experimental and computational focus were developed.9 The Mouse Brain Organization and Human Brain Organization Platforms were initiated to further knowledge of brain structure and function through more experimentally centered approaches. The Systems and Cognitive Neuroscience Platform employed both computational and experimental approaches to study behavioral and cognitive phenomena such as context-dependent object recognition. The Theoretical Neuroscience Platform and Brain was created to build large computational models starting at the cellular level, closely mirroring the original Blue Brain Project.

In addition to these, several overlapping platforms were initiated.9 The Neuroinformatics Platform seeks to organize databases containing comprehensive information on rodent and human brains as well as three-dimensional visualization tools. The High Performance Analytics and Computing Platform (HPAC) centers on managing and expanding the supercomputing resources involved in the HBP. In the longer term, HPAC may help the HBP obtain exascale computers, capable of running at least a quintillion floating point operations per second. Exascale computers would have the ability to simulate the entire human brain at the high level of detail found in the first simulated neocortical column from 2007.4 The Medical Informatics platform focuses on collecting and analyzing medically relevant brain data, particularly for diagnostics.9 The Brain Simulation Platform is related to the Theoretical Neuroscience Platform, but more broadly explores models at differing resolutions (i.e. molecular, subcellular, simplified cellular, and models which switch between resolutions during the simulation). The Neuromorphic Computing Platform tests models using computer hardware that more closely approximates the organization of nervous tissue than traditional computing systems. Finally, the Neurorobotics Platform develops simulated robots which use brain-inspired computational strategies to maneuver in their virtual environments.

Through the introduction of these platforms, the HBP collaborative may yield new insights in diverse areas of neuroscience and neurotechnology. The HBP’s original mission of simulating the human brain will continue, but with along a more interdisciplinary path. The incorporation of experimental emphases may help build more complete maps of the brain at multiple scales, enabling the development of superior simulated models as the project evolves.

The Future

As a European Flagship, the HBP will receive funding over a ten year period that started in 2013.9 It may yield advances in numerous neuroscientific fields as well as in computer science and robotics. The HBP is also open to further collaboration with other neuroscience projects such as the American BRAIN Initiative. The Theoretical Neuroscience and Brain Simulation platforms may unify experimental knowledge and pave the way to emulating a brain in a supercomputer. As exascale supercomputers emerge and the human connectome continues to be revealed, this challenging goal may be achievable. With the massive funding and resources available, the HBP may significantly advance understanding of the human brain and its operations.

The eventual completion of the HBP may have tremendous implications for the more distant future. Insights into brain mechanisms may help to decipher the mystery of consciousness. Such understanding may open the door to constructing intelligent machines.4 With the capacity to emulate consciousness in a computational substrate, prosthetic neurotechnologies10 may see remarkable advances. We may uncover methods for gradually replacing portions of the brain with equivalent computational processing systems, enabling mind uploading. Although these possibilities currently seem fantastical, exponential trends in technological advancement11 suggest that they may transition into real possibilities within the next hundred years. The HBP demonstrates that collaborative innovation is vital for building the future and continuing the human quest to invent, experience, and discover.

References

(1) Azevedo, F. A., Carvalho, L. R., Grinberg, L. T., Farfel, J. M., Ferretti, R. E., Leite, R. E., Jacob, W. F., Lent, R., Herculano-Houzel, S. (2009). Equal numbers of neuronal and nonneuronal cells make the human brain an isometrically scaled-up primate brain. The Journal of Comparative Neurology, 513(5), 532-541. doi:10.1002/cne.21974

(2) Pakkenberg, B. (2003). Aging and the human neocortex. Experimental Gerontology, 38(1-2), 95-99. doi:10.1016/s0531-5565(02)00151-1

(3) Grillner, S., Ip, N., Koch, C., Koroshetz, W., Okano, H., Polachek, M., Mu-Ming, P., Sejnowski, T. J. (2016). Worldwide initiatives to advance brain research. Nature Neuroscience, 19(9), 1118-1122. doi:10.1038/nn.4371

(4) Markram, H., Meier, K., Lippert, T., Grillner, S., Frackowiak, R., Dehaene, S., Knoll, A., Sompolinsky, H., Verstreken, K., DeFelipe, J., Grant, S., Changeux, J., Saria, A. (2011). Introducing the Human Brain Project. Procedia Computer Science, 7, 39-42. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2011.12.015

(5) Hodgkin, A. L., & Huxley, A. F. (1952). A quantitative description of membrane current and its application to conduction and excitation in nerve. The Journal of Physiology, 117(4), 500-544. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1952.sp004764

(6) Markram, H. (2006). The Blue Brain Project. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 7(2), 153-160. doi:10.1038/nrn1848

(7) Markram, H., Muller, E., Ramaswamy, S., Reimann, M., Abdellah, M., Sanchez, C., … Schürmann, F. (2015). Reconstruction and Simulation of Neocortical Microcircuitry. Cell, 163(2), 456-492. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.029

(8) Frégnac, Y., & Laurent, G. (2014). Neuroscience: Where is the brain in the Human Brain Project? Nature, 513(7516), 27-29. doi:10.1038/513027a

(9) Amunts, K., Ebell, C., Muller, J., Telefont, M., Knoll, A., & Lippert, T. (2016). The Human Brain Project: Creating a European Research Infrastructure to Decode the Human Brain. Neuron, 92(3), 574-581. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2016.10.046

(10) Deadwyler, S. A., Hampson, R. E., Song, D., Opris, I., Gerhardt, G. A., Marmarelis, V. Z., & Berger, T. W. (2016). A cognitive prosthesis for memory facilitation by closed-loop functional ensemble stimulation of hippocampal neurons in primate brain. Experimental Neurology. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2016.05.031

(11) Kurzweil, R. (2005). The Singularity is Near: When Humans Transcend Biology. New York: Viking.

(12) Chalmers, D. J. (2014). Uploading: A Philosophical Analysis. Intelligence Unbound, 102-118. doi:10.1002/9781118736302.ch6

(13) [The IBM Blue Gene/P supercomputer installation at the Argonne Leadership Angela Yang Computing Facility located in the Argonne National Laboratory, in Lemont, Illinois, USA.]. (2007, December 10). Retrieved June 20, 2017, from wikimedia.org