PDF version: Notes on Classical Mechanics – by Logan Thrasher Collins

These notes will cover the basics of Lagrangian mechanics and Hamiltonian mechanics using linear oscillatory motion as a lens (including coupled oscillations). I will assume that the reader already has knowledge of Newtonian mechanics at the level of a typical introductory physics course. That said, these notes are targeted towards readers who want to apply mechanics in engineering disciplines. I will not go much into derivations or at all into proofs, but rather present mechanics as a tool for solving engineering problems.

Lagrangian mechanics

Overview of Lagrangian mechanics

Although Newtonian mechanics is useful in many situations, there exist many mechanical systems for which Newtonian methods are difficult to apply. One way of circumventing a cumbersome Newtonian problem is to utilize the Lagrangian method instead.

Lagrange’s method centers around a quantity known as the Lagrangian L. This quantity is equal to the system’s kinetic energy T minus the system’s potential energy V (see the first expression below). The Lagrangian is needed for a differential equation called the Euler-Lagrange equation (see the second expression below). Here, q represents the generalized coordinates of the system. The concept of generalized coordinates will be explained subsequently. As one example, q could equal the one-dimensional position x of a free particle. When the Euler-Lagrange equation is simplified, it reduces to a differential equation that describes the motion of the desired system. Solving that differential equation gives the equations of motion for the system.

Generalized coordinates

Generalized coordinates qi are any set of independent coordinates that can uniquely specify the configuration of a system. Because they are independent variables, generalized coordinates cannot exhibit any functional relationship to each other. Because they specify the configuration of the system, if all the generalized coordinates are known, all positions of every part of the system can be found.

In practice, generalized coordinates are typically displacements and angles. Cartesian coordinates, polar coordinates, and more can be equivalent to generalized coordinates. Note that one system can have many sets of generalized coordinates. However, it is typically most useful to choose a set that has the fewest possible generalized coordinates.

When the fewest possible generalized coordinates are chosen, they can be used to determine the system’s configuration in any other coordinate system. For instance, consider a 2D pendulum with a particle at the end of a swinging rod of length p. One of the sets of generalized coordinates with the fewest possible variables consists of just θ, the angle between the pendulum and its equilibrium position (straight down). To obtain the Cartesian coordinates in terms of θ, one can use the expression (x, y) = (psinθ, pcosθ). As is clear from this example, the single generalized coordinate fully specifies the configuration of the pendulum system.

To further explore generalized coordinate systems, some key examples of generalized coordinates are given in the following table. While there are infinite possible systems to explore, these examples should help to give some intuition regarding how to implement generalized coordinates.

Lagrangian mechanics is typically most useful for constrained systems rather than unconstrained systems. To understand the meanings of constrained and unconstrained, realize that the cases of the systems above that are unconstrained include the free particle systems and the cases of the systems above that are constrained include the single 2D pendulum, the double 2D pendulum, and the 1D spring system.

Using the Euler-Lagrange equation

As mentioned earlier, employing the Euler-Lagrange equation first requires computing the Lagrangian L = T – V. Next, one must find the derivatives ∂L/∂q, ∂L/∂q̣̇. Note that, since q̣̇ is a time derivative of a position coordinate, it is a velocity variable. Once these derivatives are found, one must differentiate the result of ∂L/∂q̣̇ with respect to time. Put these results back into the Euler Lagrange equation and simplify. This will produce a differential equation that describes the motion of the system. Solving the differential equation will give the system’s equations of motion. Note that it is often necessary to solve the resulting differential equation numerically.

To further illustrate how to apply the Euler-Lagrange equation, consider the system of the fixed spring linked to a mass. The following series of equations shows how to find the differential equation describing this system. Recall that the kinetic energy of a moving mass is 0.5mv2 and the potential energy of a spring is 0.5kx2.

When applying the Lagrangian method, it is useful to understand ignorable coordinates. If a coordinate qi is ignorable, the corresponding generalized momentum pi = ∂L/∂q̣̇i must be constant. When the generalized momentum pi is constant, ∂L/∂qi = 0 for the generalized coordinate qi. Ignorable coordinates can simplify Lagrangian problems since L no longer depends on the ignorable coordinate q. However, it should be noted that q̣̇ is not always a constant, so the Lagrangian often still depends on q̣̇.

Another advantage of the Lagrangian method over the Newtonian method is that any set of generalized coordinates q can be transformed to a new set of generalized coordinates Q(q) where each new Qi is some function of the original q1 … qn and the Euler-Lagrange equations will still be valid with respect to the new coordinates.

Linear oscillations

Simple harmonic motion

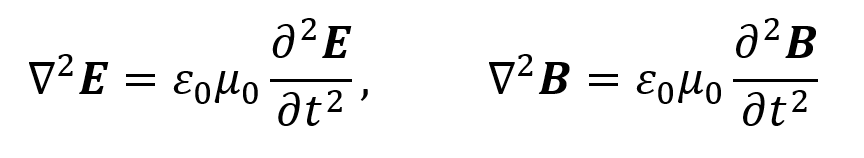

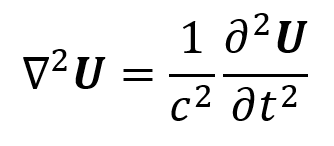

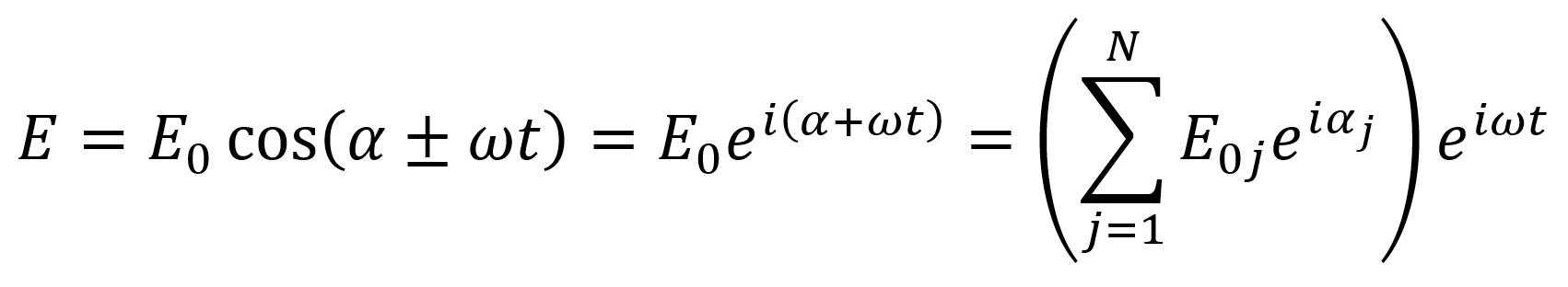

Simple harmonic motion (SHM) is an important type of oscillation which happens when the acceleration of a mass is linearly proportional to its displacement from an equilibrium position and is directed towards the equilibrium position. In SHM, there is no loss of energy. SHM in 1D is mathematically described by the following differential equation. Some examples of SHM include the oscillations of simple springs and pendulums. For a simple spring system, ω2 = k/m. For a simple pendulum system, ω2 = g/L. (The constant ω is the angular frequency).

![]()

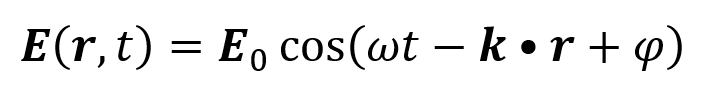

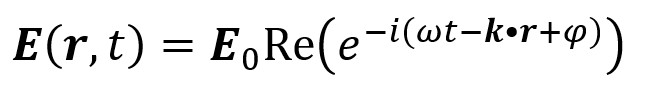

There are several equivalent ways of writing the solution to the SHM differential equation, each of which has benefits and drawbacks. The exponential solution to the SHM equation is the first expression given below. The sine and cosine solutions arise by using Euler’s formula eiωt = cos(t) + isin(t) and are given by the second expression below. B1 is the initial position and ωB2 is the initial velocity.

Another equivalent way of writing the solution to the SHM equation is to use the phase-shifted cosine solution. The phase-shifted cosine solution is given as the first equation below. Here, A is a constant describing the amplitude of the oscillations. The constant A can also be computed using the constants B1 and B2 which were described above. Finally, the solution to the SHM equation can be written as the real part of a complex exponential. This version of the solution is given by the second equation below.

To extend SHM to the 3D case, the differential equation describing the system is split into three independent differential equations for the x, y, and z directions. Solving these differential equations gives the equations of SHM for x, y, and z. The 2D case is the same, but with only two independent differential equations. There are a variety of interesting graphical phenomena that come out of plotting 2D and 3D SHM equations, especially when there are different values of ω, A, or δ for x, y, and z.

Damped oscillations

When some force resists oscillatory motion (e.g. friction, air resistance, etc.), causing energy loss over time, the resulting system undergoes damped oscillations. This type of system is described by the differential equation where b is a damping constant (see the first expression below). To make later calculations easier, the differential equation can be rewritten with alternative constants 2β = b/m and ω02 = k/m. The general solution to this differential equation is given by the second formula below.

To understand the solution above, it is helpful to consider three cases: underdamping where β < ω0, overdamping where β > ω0, and critical damping where β = ω0. The solution above simplifies to different forms depending on whether β < ω0, β > ω0, or β = ω0. These results are summarized in the following table. After the table, plots of x(t) for the underdamped, overdamped, and critically damped cases are given.

Driven damped oscillations

When an external force influences a damped oscillating system, driven damped oscillations occur. Mathematically, this is described by setting the differential equation for the damped oscillator equal to a function f(t) instead of zero. Here, f(t) represents the amount of external force acting on the system as a function of time.

![]()

To find the general solution to the above differential equation, one must first solve the differential equation where f(t) = 0. This solution, called the homogenous solution xh, is already known from the undriven damped oscillation case. Next, one must find the particular solution xp. The particular solution is any solution which solves the differential equation for the given nonzero force function f(t). The general solution to the differential equation of driven damped oscillations is equal to xh + xp.

One useful special case to consider is when a driving force of the form f(t) = f0cos(ωt) is applied. In this case, f0 is the amplitude of the driving force divided by the oscillator’s mass and ω is the driving force’s frequency. Note that ω is a distinct parameter from the oscillation frequency ω0. The differential equation for this system and its general solution are given below. Note that the non-cosine term in the expression for x(t) is the homogenous solution. Because this non-cosine term decays over time, it only contributes to the waveform during the early stages of the oscillations.

Resonance

Consider the previously described case of the driven damped oscillator where the driving force is a sinusoidal function (which includes cosine). More specifically, let β take on a fairly small value. In this situation, when the frequency ω of the driving force is close to the frequency of the oscillator ω0, the amplitude of the driven oscillations grows very large.

The reason for this comes from the denominator of the amplitude A (see previous section). When β is small, the (ω02 – ω2)2 term is responsible for determining most of the value of the denominator. If ω0 and ω are close together, (ω02 – ω2)2 takes on a very small value. Since this term is in the denominator, a very small value leads to a very large amplitude A. This phenomenon is called resonance. To better understand resonance, see the plot of A2 versus ω below.

Resonance can be further characterized by computing the maximum amplitude Amax of oscillations where ω = ω0. This quantity is given by the following equation.

Another way to characterize resonance is by finding the quality factor or Q factor. The Q factor describes the sharpness of the resonance peak and is often defined by the equation below. Note that 2β approximately equals the full width at half maximum (FWHM), the width of the resonance peak where at A = Amax/2. When Q is large, the resonance peak is narrow and vice versa. The Q factor is also useful because Q/π = the number of cycles the oscillator makes during one decay time. The decay time is defined as the amount of time it takes for the amplitude to drop to 1/e of its initial value.

Finally, it can be useful to note that the phase shift at resonance is π/2. The reason for this is that ω02 – ω2 = 0 at resonance and the equation for the phase shift is arctan(2βω/( ω02 – ω2)). The zero in the denominator results in an arctangent of infinity, which equals π/2.

Coupled linear oscillations

Case of two masses linked by springs

To understand coupled linear oscillations, it is often helpful to consider the case of two masses linked by springs that are fixed to walls as seen in the image below. Here, m1 and m2 refer to the masses and k1, k2, k3 are the spring constants.

This system can be solved by Newtonian or Lagrangian methods. Here, the Lagrangian approach will be employed. Recall that the Lagrangian L = T – V. The kinetic energy T is found as the sum of the kinetic energies of the masses as shown in the first equation below. The potential energy V requires carefully evaluating the extensions of the springs. In this system, the respective extensions of the three springs are x1, x2 – x1, and –x2. Using this information and Hooke’s law Fs = –kx, the potential energy is given by the second equation below. The Lagrangian L is given by the third equation below.

Using the Euler-Lagrange equation (see the first equation below), the Lagrangian above reduces to the equations of motion for the system (see the second equation below). By rearranging the spring constants, these equations of motion can be written in matrix form (see the equivalent third and fourth equations below).

Solutions to this system of equations can be written in the complex form as seen below. Here, p1 and p2 are arbitrary constants and the actual motions of the masses are determined by Re(z(t)). Note that, although the frequency ω is assumed to be the same for z1(t) and z2(t), there are actually two solutions for ω (this will be explained subsequently).

By substituting the above equation into the matrix equation for the coupled oscillator system, the following eigenvalue equation for K can be obtained.

The characteristic polynomial which results after taking the above determinant is a quadratic equation with two solutions for ω2. As a result, there are two frequencies ω1 and ω2 at which the masses can oscillate. These are called the normal frequencies of the system. The equations governing the motion of the system at each normal frequency are called the normal modes of the system.

The general solution for the case of two masses linked by springs system is given as follows. The vectors are the eigenvectors from the eigenvalue equation of K. Note that this solution is a linear combination of the two normal mode solutions. As usual, the constants A1, A2, δ1, and δ2 are determined by initial conditions.

To better understand normal modes, it can be helpful to investigate the specific case where k1 = k2 = k3 = k and m1 = m2 = m. In this situation, the eigenvalue equation reduces to the first expression below. The normal frequencies are the solutions to this eigenvalue equation and are given by the second expression below.

Similarly, there are two normal frequencies for the general solution. However, the normal frequencies of the general solution are much more elaborate and so will not be written out here. If one needs the normal frequencies of the general solution, they can be obtained by solving its characteristic polynomial equation (most easily by using a computer algebra system).

Going beyond the case of the two masses linked by springs, for a similar system with N coupled masses, there are N normal frequencies and the equation of motion for each mass consists of superpositions of N normal modes. This principle also extends to other types of oscillators such as coupled pendulums.

Hamiltonian mechanics

Overview of Hamiltonian mechanics

To understand Hamiltonian mechanics, it can be helpful to first further examine Lagrangian mechanics. With Lagrangian mechanics, the n generalized position coordinates and their n derivatives define a set of possibilities called a state space. By using the Euler-Lagrange equation, the state space reduces to the equations of motion for the system. Each set of initial conditions then determines a unique path of the components of the system through state space.

For Hamiltonian mechanics, it is also important to reiterate the generalized momentum where qi are the generalized coordinates of the system (see below). Note that, if qi are Cartesian coordinates, then the generalized momentum is equivalent to the usual momentum.

While Lagrangian mechanics employs n generalized position coordinates and their n derivatives, Hamiltonian mechanics instead uses n generalized position coordinates and n generalized momenta. These n generalized position coordinates and generalized momenta are called the phase space of the system. Each set of initial conditions determines a unique path of the components of the system through phase space.

The Hamiltonian and Hamilton’s equations

To achieve this, the Hamiltonian H and Hamilton’s equations are used. The Hamiltonian is a quantity that often holds equivalent to the total energy of the system. Here, pi are the generalized momenta, L is the Lagrangian, and q̣̇i are the generalized position coordinates.

When the relationship between the generalized coordinates and the underlying Cartesian coordinates is independent of time (often the case), the Hamiltonian is equal to the total energy as H = T + V. However, the above equation (more general) should be used when the conversion between the generalized coordinates and Cartesian coordinates might depend on time.

Hamilton’s equations use the Hamiltonian to derive equations of motion for a system. By contrast to the Euler-Lagrange method which reduces a system with n degrees of freedom to n second-order differential equations, Hamilton’s method instead reduces a system to 2n first-order differential equations, which can sometimes be advantageous. Note that degrees of freedom are the number of independent parameters needed to define the state of a system. For many systems, the degrees of freedom are equal to the number of generalized coordinates (when this is the case, the system is called holonomic). Hamilton’s equations for i = 1, 2, 3… n are given as follows.

The results of Hamilton’s equations can be combined with each other to produce the equations of motion for a given system.

Using Hamilton’s equations

As an example of how to apply Hamilton’s equations, consider the system of two masses linked by three springs with fixed walls at the edges (see the image in the previous section). For this system, the Hamiltonian is equivalent to the total energy as H = T + V (since the only generalized coordinate is x, which is already a Cartesian coordinate and so does not depend on time to undergo conversion to Cartesian coordinates). The Hamiltonian is given by the first equation below. Hamilton’s equations and their results are given by the second, third, and fourth lines of the equations below. Recall that the derivative of momentum is equivalent to force.

As with the Lagrangian method, when applying Hamilton’s equations, it is useful to understand ignorable coordinates. If a coordinate qi is ignorable, the corresponding generalized momentum pi must be constant. When the generalized momentum pi is constant, –∂H/∂qi = ∂L/∂qi = 0 for the generalized coordinate qi. Note that, if a generalized coordinate is ignorable for the Lagrangian approach, it is also ignorable for the Hamiltonian approach and vice versa.

Ignorable coordinates lead to an elegant simplification of the Hamiltonian. If a system has an ignorable coordinate q, then the Hamiltonian H will no longer depend on q and the corresponding momentum p will be absorbed into the Hamiltonian as a constant. As an example, consider a system with two generalized coordinates q1 and q2, but the q2 is an ignorable coordinate. The Hamiltonian will depend on H(q1, p1, k) where k = p2. As a result, each ignorable coordinate decreases the number of degrees of freedom by one when employing the Hamiltonian approach. By contrast, this is not always true for the Lagrangian approach since even if q is ignorable and p is a constant, q̣̇ is not always a constant.

An advantage of the Hamiltonian method over the Newtonian and Lagrangian methods is that Hamilton’s equations are even more flexible than the Euler-Lagrange equation when it comes to coordinate changes. Under certain conditions, changes of both generalized coordinates and generalized momenta of the forms Q(q,p) and P(q,p), preserve the validity of Hamilton’s equations (with respect to the new coordinates and momenta). When these changes preserve the validity of Hamilton’s equations, the changes are called canonical transformations. But as mentioned, canonical transformations only work under certain conditions. The conditions for a transformation to be canonical are given by the equations below. The subscripts denote variables which must be held constant for the formulas in parentheses.

The Hamiltonian method and phase space

Another advantage of the Hamiltonian method over the Lagrangian method is that Hamilton’s equations are automatically of the form dz/dt = h(z). There are many mathematical tools available for working with differential equations of this form. One of the most important of these tools is phase space analysis.

In Hamiltonian mechanics, the phase space vector is a 2n-dimensional vector z(q,p) where q is all of the generalized coordinates and p is all of the generalized momenta. Each value of z identifies a unique set of initial conditions for the system. With this notation, the equation h(z) is an expression of Hamilton’s equations as a first-order differential equation. Here, h is a vector of the functions fi = ∂H/∂pi and gi = –∂H/∂qi.

Trajectories in the phase space with axes given by the elements of z(q,p) are vital in Hamiltonian mechanics. Any point z0 at a time t0 defines a unique trajectory in phase space of z. Since phase space vectors have 2n elements, it is difficult to visualize phase space for systems with more than one generalized coordinate, though there are methods to aid such visualization.

It is important to note that, for a given point in phase space, only a single trajectory can pass through that point across all times t. If there appear to be two trajectories crossing the same point, the trajectories must represent the same path looping back on itself. This property follows from Hamilton’s equations.

As an example of a phase space trajectory, consider the one-dimensional harmonic oscillator. For this system, the Hamiltonian is H = T + V = p2/2m + 0.5mω2x2 where k = mω2. Hamilton’s equations give ẋ = ∂H/∂p = p/m and ṗ = ∂H/∂p = –mω2x. By differentiating ẋ to get ṗ/m, the equation of motion for the system is found as ẍ = –ω2x. The solution to this equation of motion is x = Acos(ωt – δ). As a result, the momentum of the system is given by p = mẋ = –mωAsin(ωt – δ). These expressions for x and p act as parametric equations that define phase space trajectories. The phase space trajectories for this system take the form of ellipses which each start from unique phase points (p,x) and which never cross over each other. Different values of A determine the unique trajectories.

Reference: Taylor, J.R. (2005). Classical Mechanics. University Science Books.

Cover image: originally created by John Harris.

state), but that to get to the folded state, the polypeptide chain must navigate past local energetic minima and energetic maxima.

state), but that to get to the folded state, the polypeptide chain must navigate past local energetic minima and energetic maxima.

can take on a variety of different configurations, but it cannot double back on itself or place two beads in the same location. In the HP model, there are two types of beads including hydrophobic beads and polar beads.

can take on a variety of different configurations, but it cannot double back on itself or place two beads in the same location. In the HP model, there are two types of beads including hydrophobic beads and polar beads.

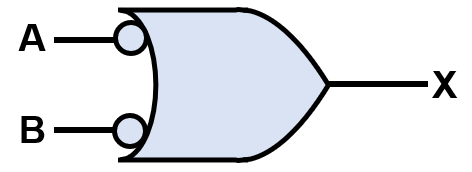

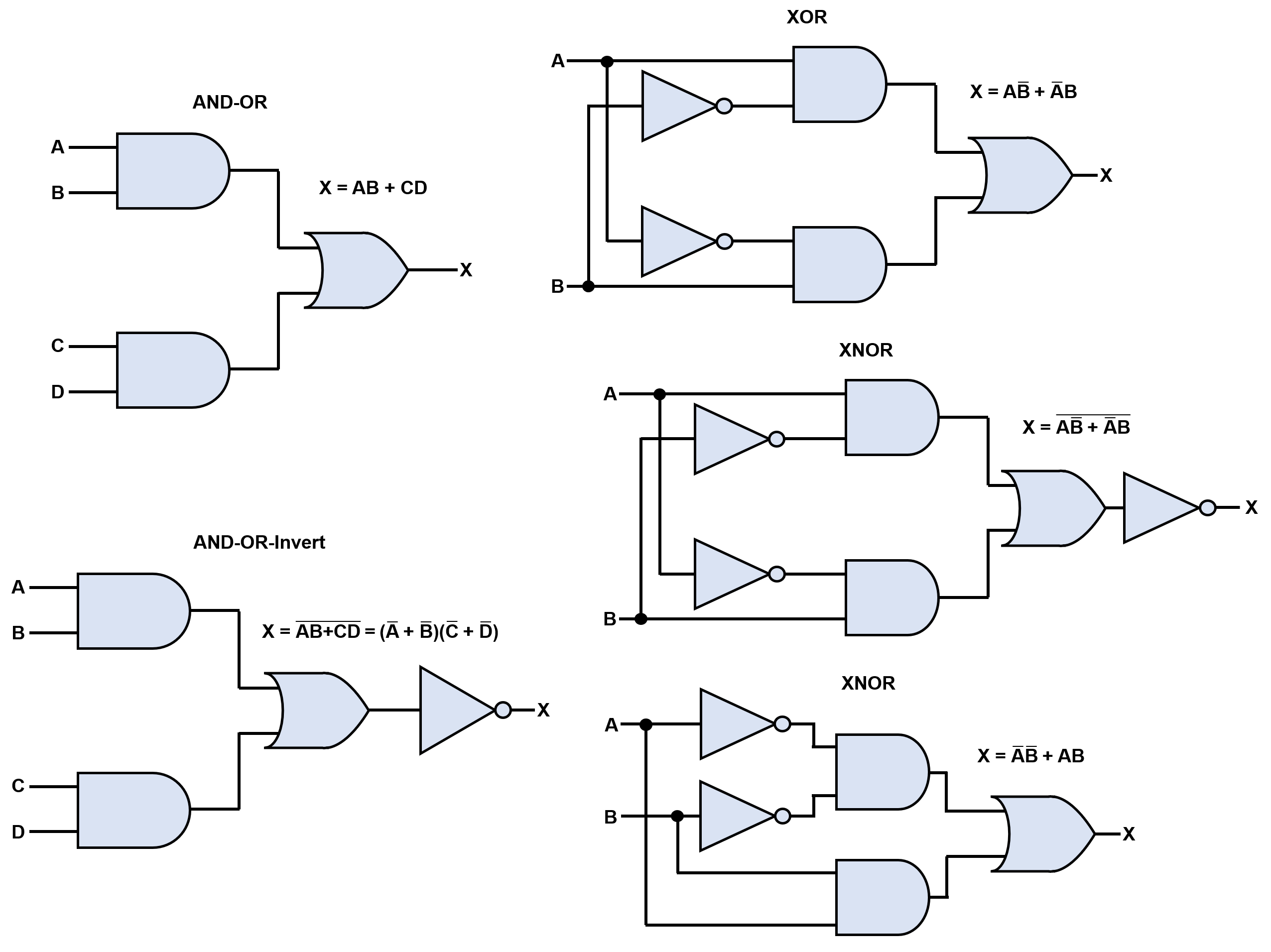

with two inputs), it acts as a “negative-OR” gate. In this case, any of the 0 inputs will give an output of 1, so the operation is similar to OR. The symbol for a negative-OR version of a NAND gate is given at right.

with two inputs), it acts as a “negative-OR” gate. In this case, any of the 0 inputs will give an output of 1, so the operation is similar to OR. The symbol for a negative-OR version of a NAND gate is given at right. as a “negative-AND” gate. In this case, all the 0 inputs together will give an output of 1, so the operation is similar to AND. The symbol for a negative-AND version of a NOR gate is given above.

as a “negative-AND” gate. In this case, all the 0 inputs together will give an output of 1, so the operation is similar to AND. The symbol for a negative-AND version of a NOR gate is given above.

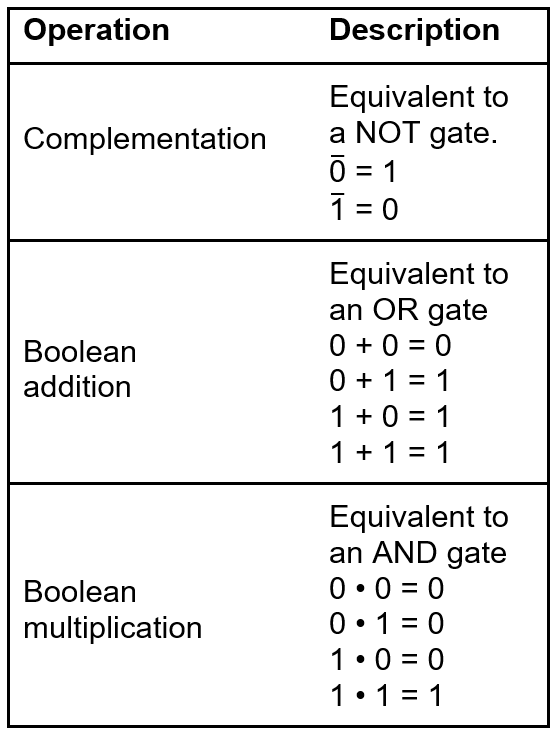

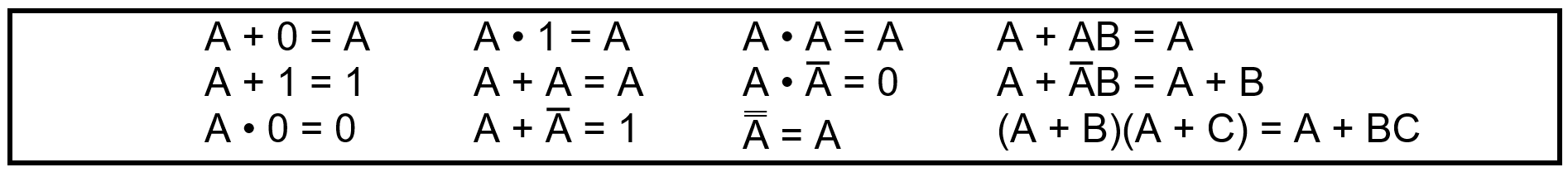

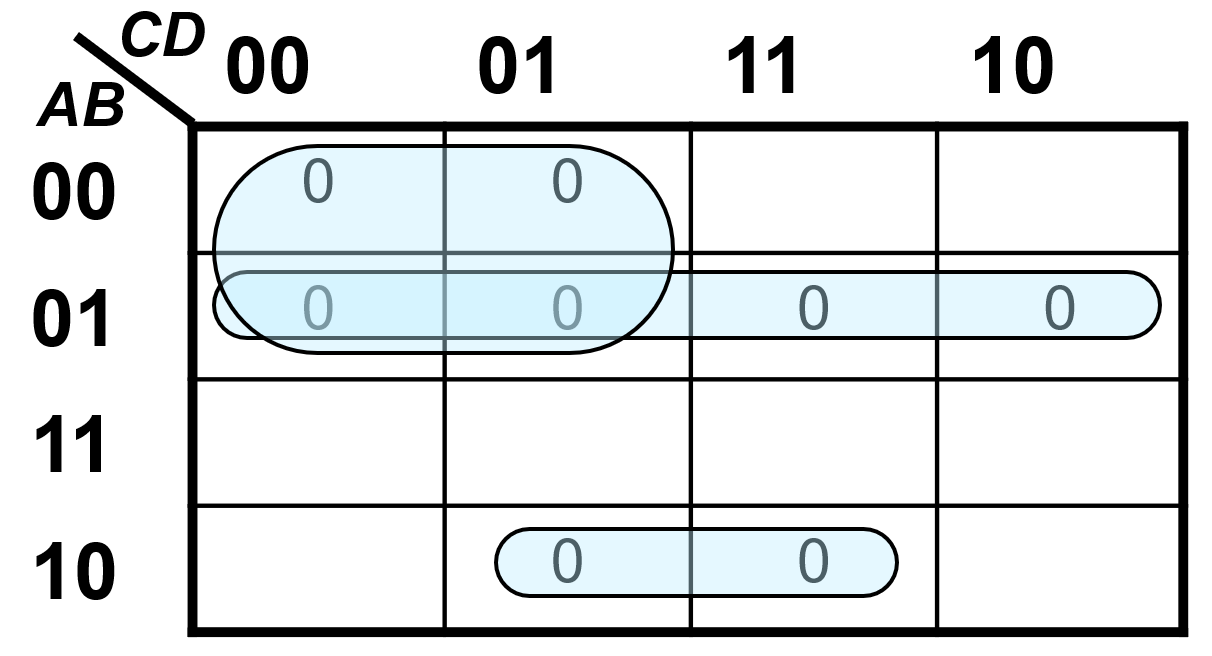

same group (but not all cells in a group need to be adjacent). Each group must contain the largest possible number of 1s. Finally, each 1 on the map must be included in at least one group. Note that a 1 can be included in overlapping groups so long as each of the groups involved also have noncommon 1s. At right, an example of grouping the 1s is displayed.

same group (but not all cells in a group need to be adjacent). Each group must contain the largest possible number of 1s. Finally, each 1 on the map must be included in at least one group. Note that a 1 can be included in overlapping groups so long as each of the groups involved also have noncommon 1s. At right, an example of grouping the 1s is displayed. group comprise a parentheses-enclosed sum term within the minimized POS expression. All of the parentheses-enclosed sum terms from the groups are multiplied to find the full minimized POS expression. “Don’t care” terms are also applied the same way for standard POS expressions as they are for standard SOP expressions.

group comprise a parentheses-enclosed sum term within the minimized POS expression. All of the parentheses-enclosed sum terms from the groups are multiplied to find the full minimized POS expression. “Don’t care” terms are also applied the same way for standard POS expressions as they are for standard SOP expressions.

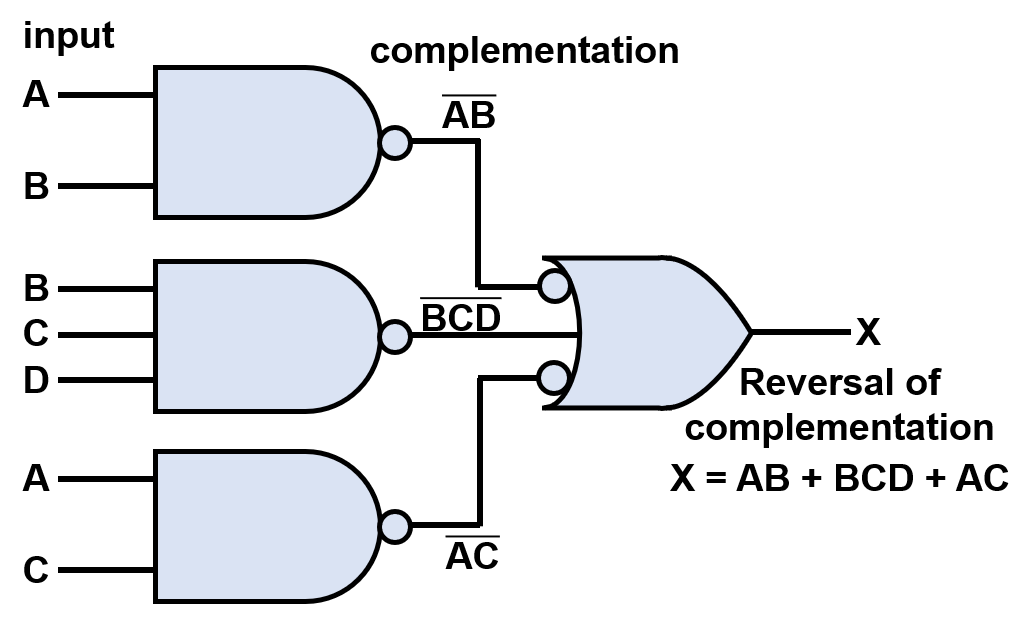

gates, the symbols should be drawn with NAND gate bubbles facing negative-OR gate bubbles to help make it easier to visualize how the inversion properties of the gates are cancelling each other out (a bubble represents that a gate carries out inversion as at least part of its operation).

gates, the symbols should be drawn with NAND gate bubbles facing negative-OR gate bubbles to help make it easier to visualize how the inversion properties of the gates are cancelling each other out (a bubble represents that a gate carries out inversion as at least part of its operation). gates, the symbols should be drawn with NOR gate bubbles facing negative-AND gate bubbles to help make it easier to visualize how the inversion properties of the gates are cancelling each other out. (As mentioned, a bubble represents that a gate carries out inversion as at least part of its operation).

gates, the symbols should be drawn with NOR gate bubbles facing negative-AND gate bubbles to help make it easier to visualize how the inversion properties of the gates are cancelling each other out. (As mentioned, a bubble represents that a gate carries out inversion as at least part of its operation).

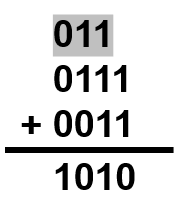

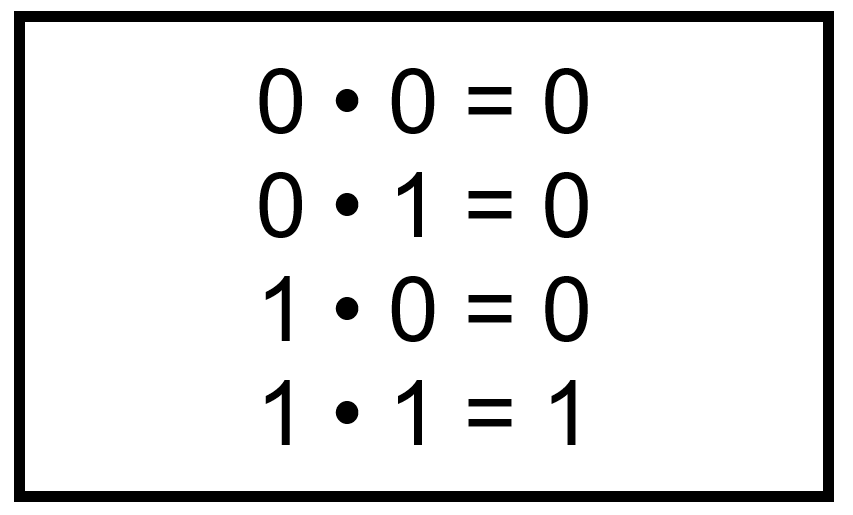

rules for addition of two bits (a bit is a single binary value) and the bottom part describes the rules for the addition of two bits plus a carry bit, which is a value that is carried in the same way as in base-10 addition. The carry bits are highlighted in gray. To illustrate this concept, an example of binary addition with carrying is also shown at right.

rules for addition of two bits (a bit is a single binary value) and the bottom part describes the rules for the addition of two bits plus a carry bit, which is a value that is carried in the same way as in base-10 addition. The carry bits are highlighted in gray. To illustrate this concept, an example of binary addition with carrying is also shown at right.

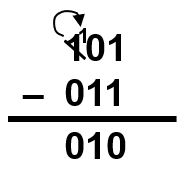

subtraction, a borrow is only needed if subtracting a 1 from a 0 digit (e.g. 110 – 1). To borrow, take a 1 from the column to the left, create a 10 in the column undergoing subtraction, and apply the rule 10 – 1 = 1. To illustrate this concept, an example of binary subtraction with borrowing is also shown at right.

subtraction, a borrow is only needed if subtracting a 1 from a 0 digit (e.g. 110 – 1). To borrow, take a 1 from the column to the left, create a 10 in the column undergoing subtraction, and apply the rule 10 – 1 = 1. To illustrate this concept, an example of binary subtraction with borrowing is also shown at right.

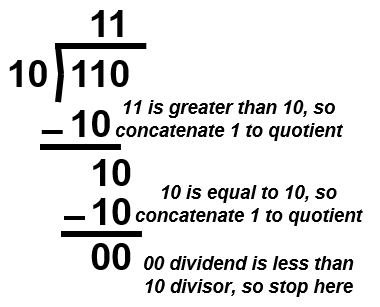

result of the subtraction below, and concatenate a 1 to the rightmost end of the quotient. If the dividend above the divisor is less than the divisor, concatenate a 0 to the rightmost end of the quotient. (4) Place another copy of the divisor at the bottom but shift it one column to the right. (5) Repeat steps 3 and 4 until the part of the dividend is less than the divisor. The result is the quotient with the dividend as a remainder. To illustrate this concept, an example of binary division is shown at right.

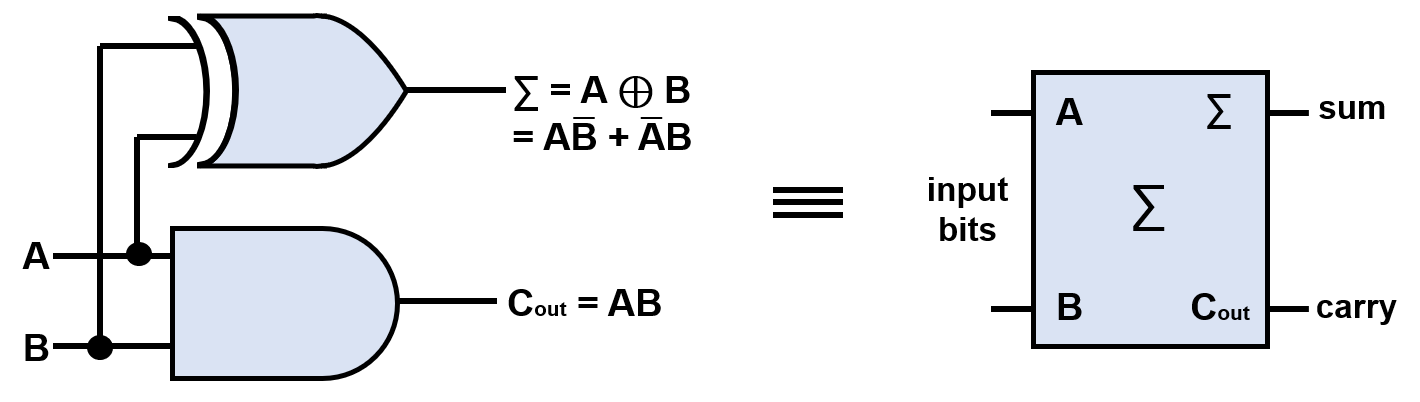

result of the subtraction below, and concatenate a 1 to the rightmost end of the quotient. If the dividend above the divisor is less than the divisor, concatenate a 0 to the rightmost end of the quotient. (4) Place another copy of the divisor at the bottom but shift it one column to the right. (5) Repeat steps 3 and 4 until the part of the dividend is less than the divisor. The result is the quotient with the dividend as a remainder. To illustrate this concept, an example of binary division is shown at right. produce outputs of 1 when the inputs are not equal, a XOR gate is used to generate the sum bit. Because AND gates only produce outputs of 1 when the inputs are both 1, an AND gate is used to generate the carry bit. The truth table for a half-adder is displayed at right. The logic gate diagram for a half-adder is shown below at left and the equivalent logic symbol is shown below at right.

produce outputs of 1 when the inputs are not equal, a XOR gate is used to generate the sum bit. Because AND gates only produce outputs of 1 when the inputs are both 1, an AND gate is used to generate the carry bit. The truth table for a half-adder is displayed at right. The logic gate diagram for a half-adder is shown below at left and the equivalent logic symbol is shown below at right.

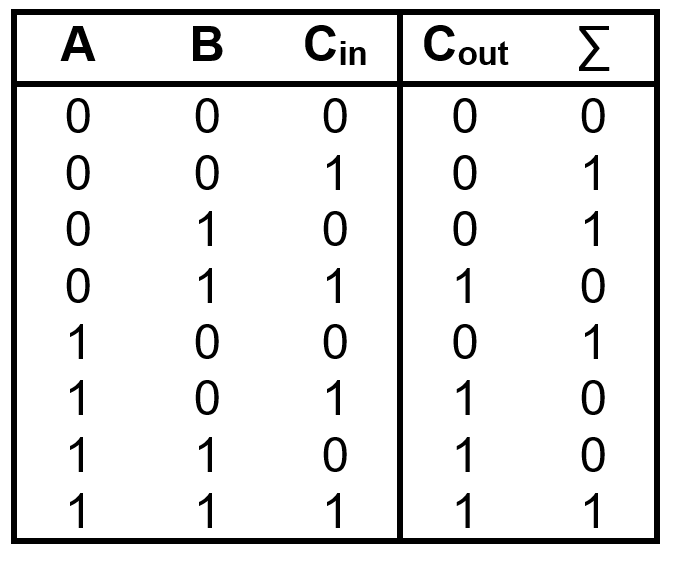

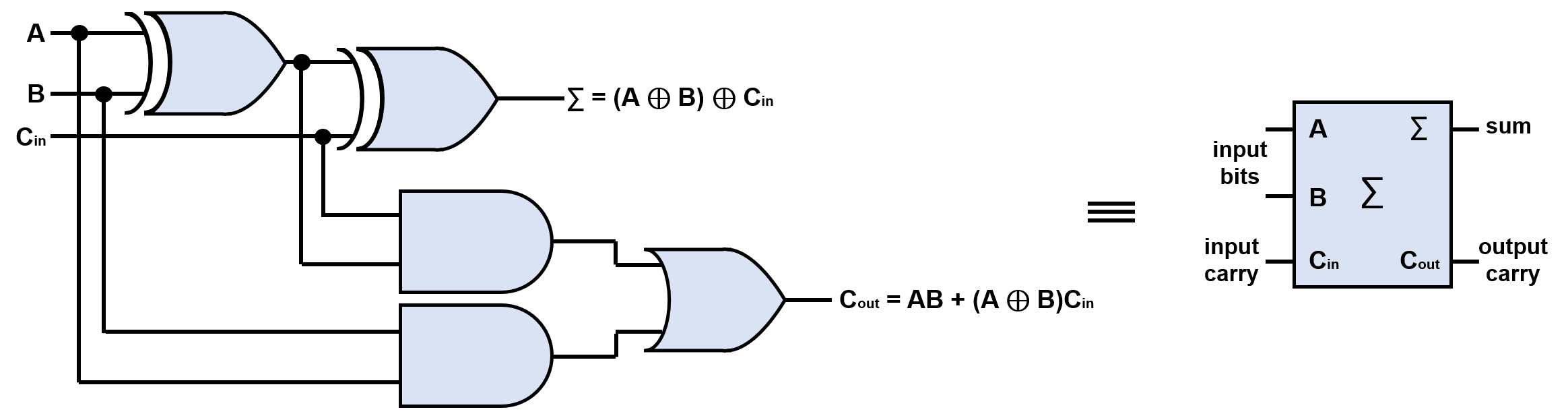

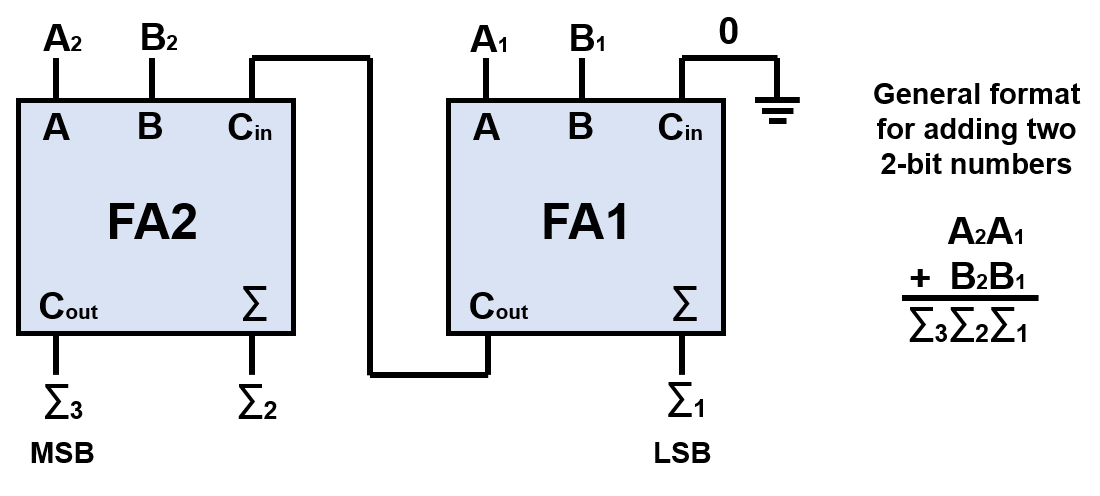

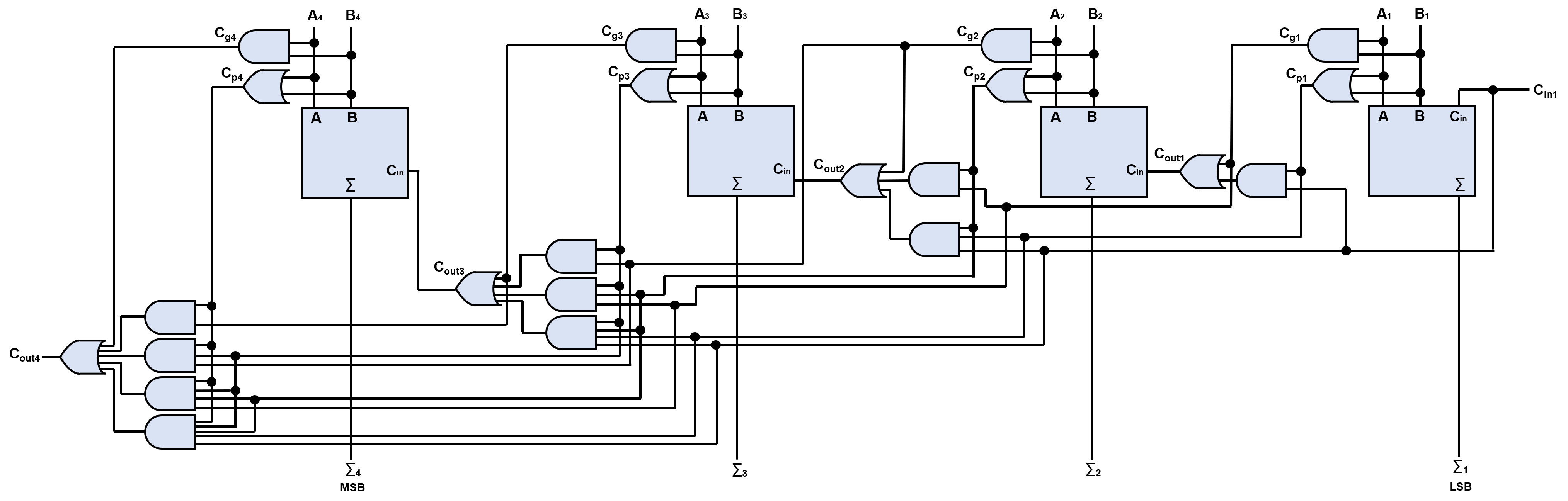

section on binary addition. Since the sum of the two input bits is A⊕B, the sum of the two input bits and the input carry is (A⊕B)⊕Cin. (Note that the circled plus indicates the XOR operation). The equation for the output carry is Cout = AB + (A⊕B)Cin. Full-adders are composed of two half-adders and an OR gate. The truth table for a full-adder is displayed at right. The logic gate diagram for a full-adder is shown below at left and the equivalent logic symbol is shown below at right.

section on binary addition. Since the sum of the two input bits is A⊕B, the sum of the two input bits and the input carry is (A⊕B)⊕Cin. (Note that the circled plus indicates the XOR operation). The equation for the output carry is Cout = AB + (A⊕B)Cin. Full-adders are composed of two half-adders and an OR gate. The truth table for a full-adder is displayed at right. The logic gate diagram for a full-adder is shown below at left and the equivalent logic symbol is shown below at right.

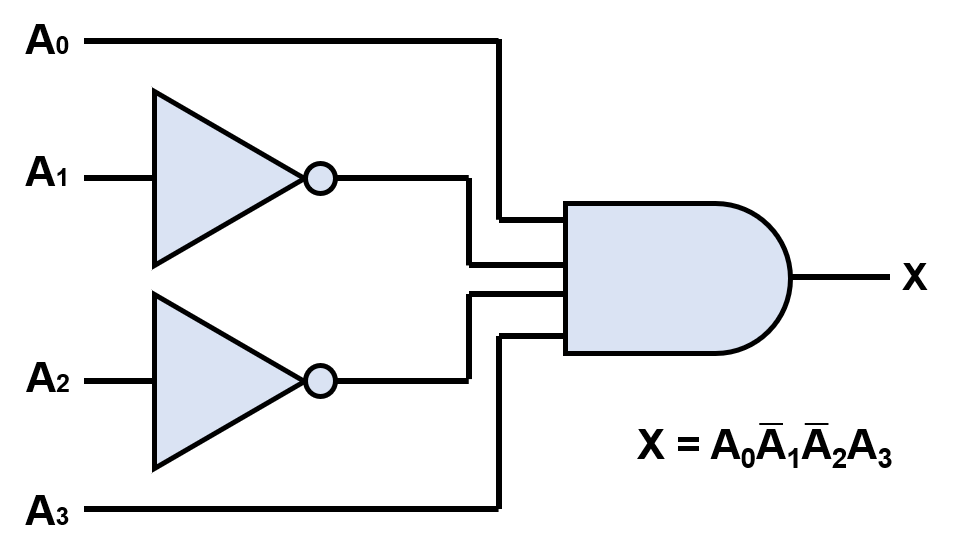

into 1s via NOT gates and then feed every input to an AND gate. Since the AND gate will only output 1 when all inputs are 1, the targeted number will be detected through the NOT gates converting all 0s in the targeted number to 1s. As an example, the logic gate implementation of a decoder which detects 1001 is shown at right.

into 1s via NOT gates and then feed every input to an AND gate. Since the AND gate will only output 1 when all inputs are 1, the targeted number will be detected through the NOT gates converting all 0s in the targeted number to 1s. As an example, the logic gate implementation of a decoder which detects 1001 is shown at right.

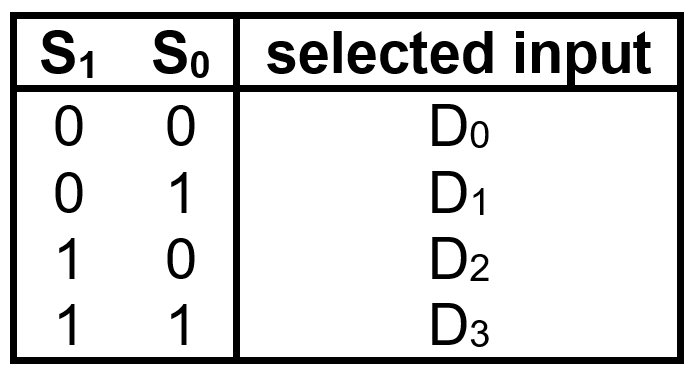

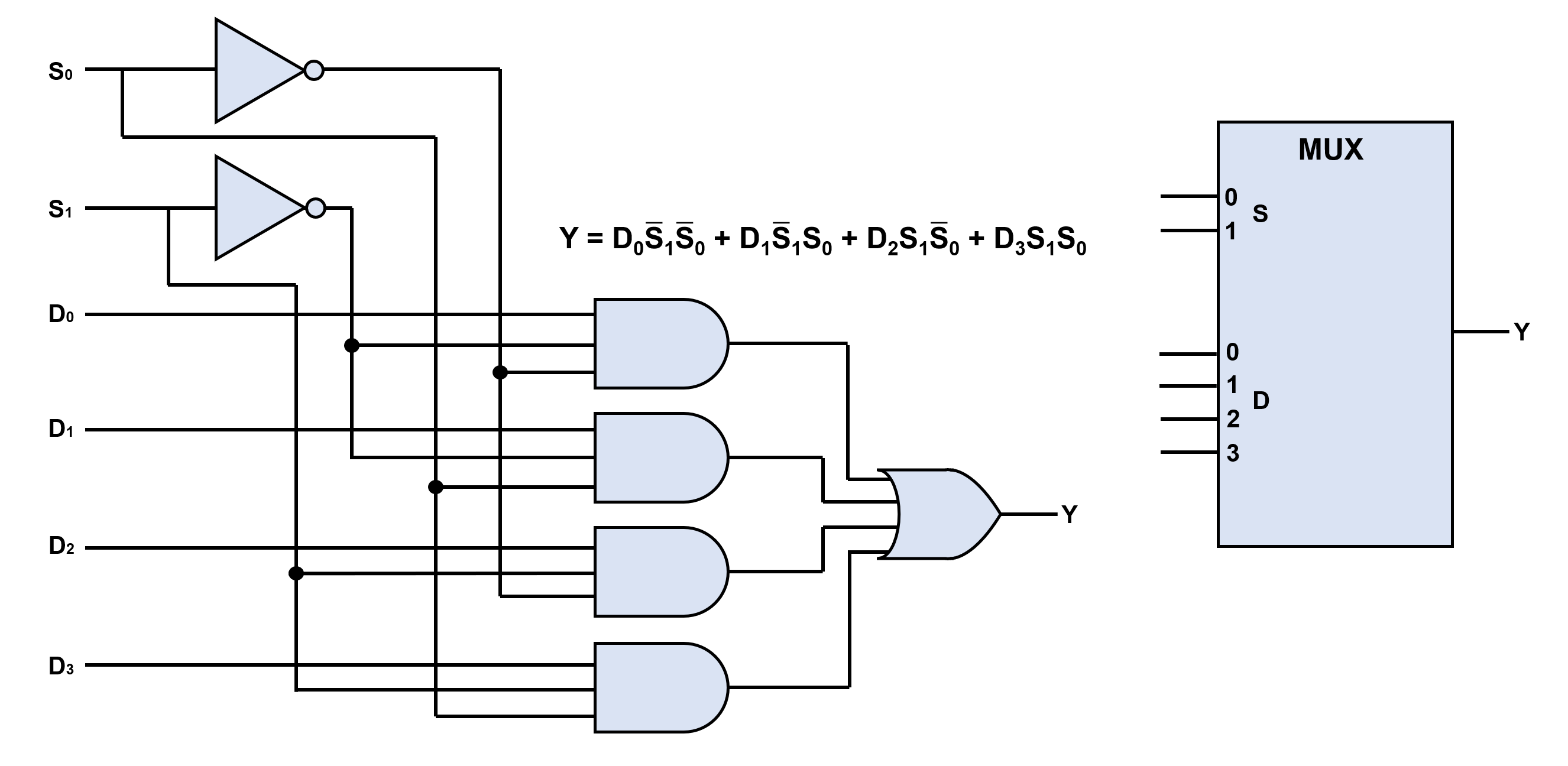

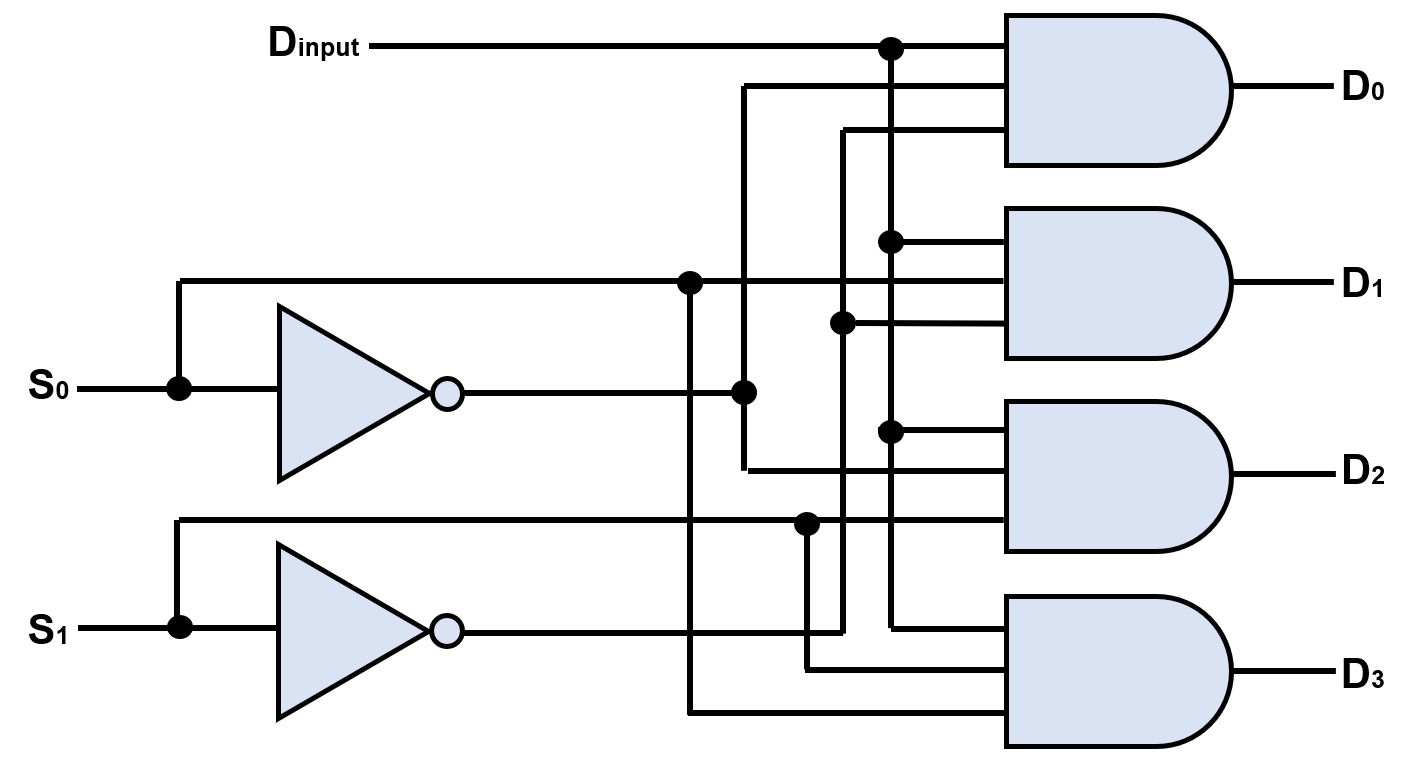

select lines which control four data-input lines. The four possible inputs to the data-select lines (00, 01, 10, and 11) control which of the four data-input lines undergoes transmission to the data-output line. The truth table for this device is displayed at right where S1 and S0 are the data-select lines.

select lines which control four data-input lines. The four possible inputs to the data-select lines (00, 01, 10, and 11) control which of the four data-input lines undergoes transmission to the data-output line. The truth table for this device is displayed at right where S1 and S0 are the data-select lines.

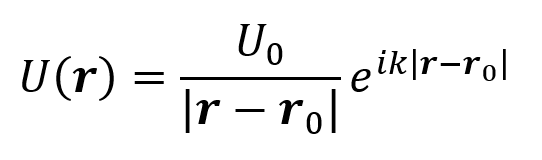

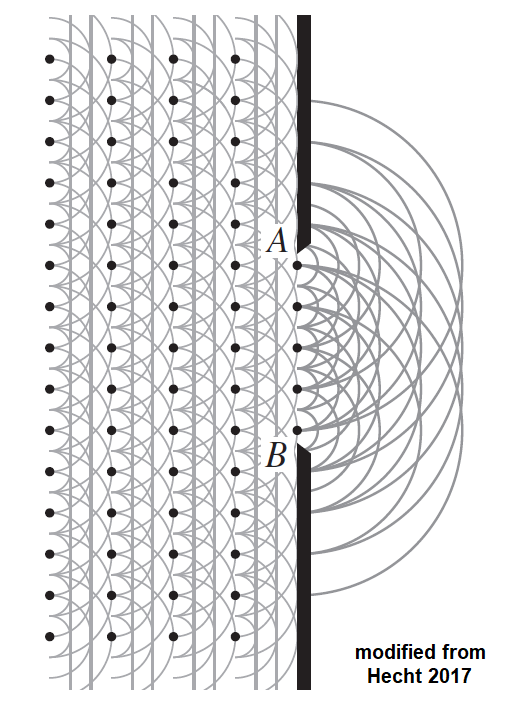

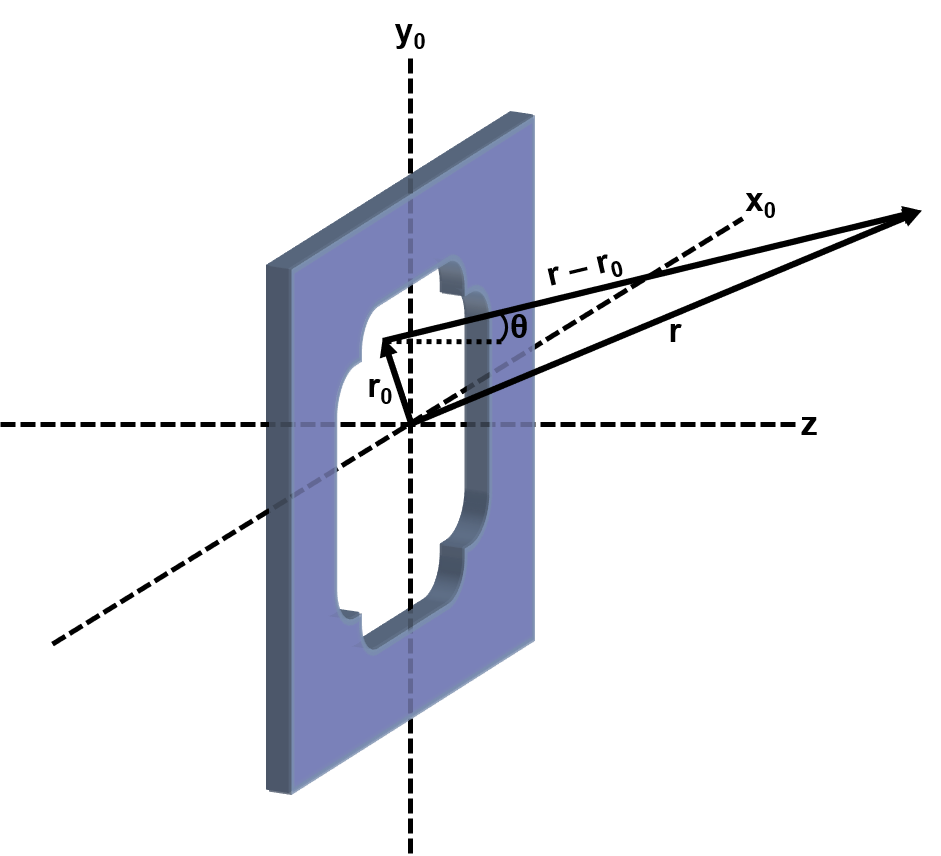

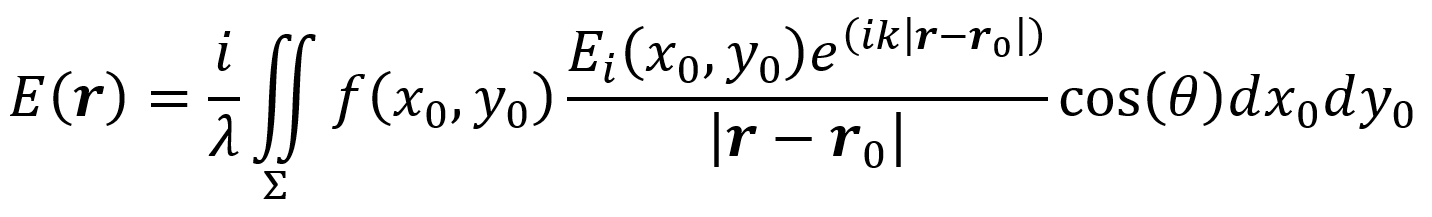

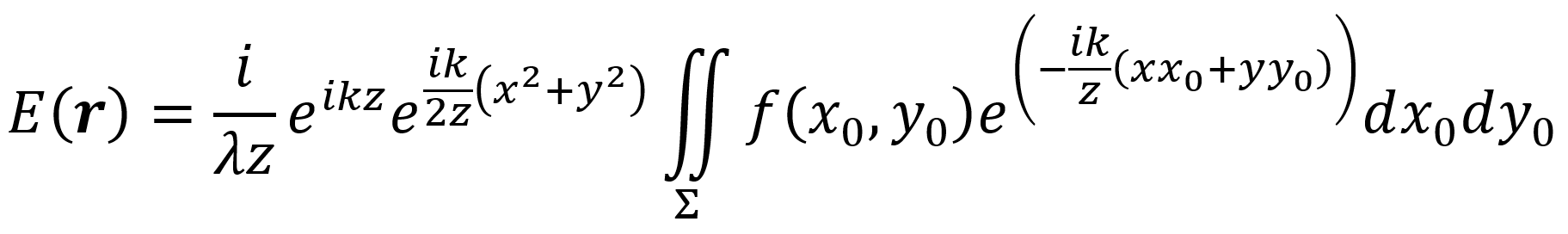

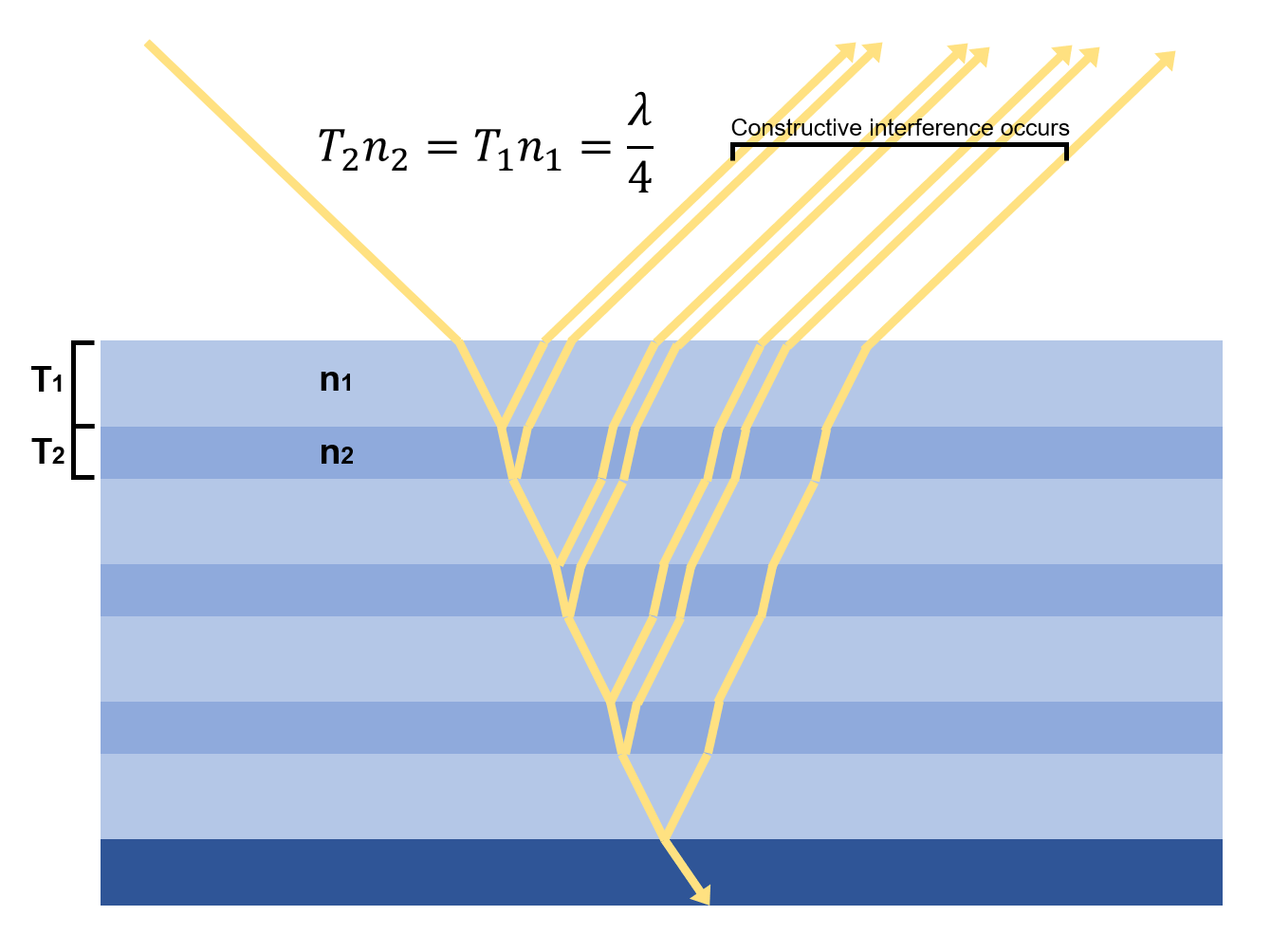

the barrier’s aperture. The constant i/λ arises as an approximation of the influence of the angle of the wave arriving at the aperture relative to the aperture’s normal vector. The domain Σ over which integration takes place is the aperture’s area and r0 represents an infinitesimal surface element of the aperture dx0dy0 (with the flat barrier and its aperture described as an xy plane). Ei(x0,y0) is the complex amplitude of the incident wave at the point x0,y0 on the flat barrier’s xy coordinate system. Here, θ represents the angle of the vector r – r0 relative to the aperture’s normal vector. A transmission function f(x0,y0) can be included inside the integral to describe the effect of a partially translucent surface. For the case of a fully opaque barrier and a fully translucent aperture, f(x0,y0) is zero at all barrier points and one at all aperture points. For a system with a partially translucent barrier or aperture, f(x0,y0) is a complex quantity with magnitudes falling between zero and one. Recall that the magnitude of a complex quantity a + bi is defined as (a2 + b2)1/2. Though it is an approximation, the Huygens-Fresnel integral is still complicated enough that it is often computed numerically.

the barrier’s aperture. The constant i/λ arises as an approximation of the influence of the angle of the wave arriving at the aperture relative to the aperture’s normal vector. The domain Σ over which integration takes place is the aperture’s area and r0 represents an infinitesimal surface element of the aperture dx0dy0 (with the flat barrier and its aperture described as an xy plane). Ei(x0,y0) is the complex amplitude of the incident wave at the point x0,y0 on the flat barrier’s xy coordinate system. Here, θ represents the angle of the vector r – r0 relative to the aperture’s normal vector. A transmission function f(x0,y0) can be included inside the integral to describe the effect of a partially translucent surface. For the case of a fully opaque barrier and a fully translucent aperture, f(x0,y0) is zero at all barrier points and one at all aperture points. For a system with a partially translucent barrier or aperture, f(x0,y0) is a complex quantity with magnitudes falling between zero and one. Recall that the magnitude of a complex quantity a + bi is defined as (a2 + b2)1/2. Though it is an approximation, the Huygens-Fresnel integral is still complicated enough that it is often computed numerically.

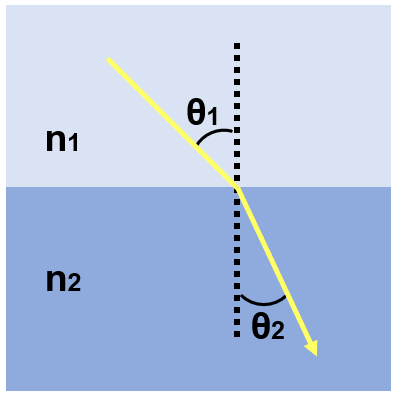

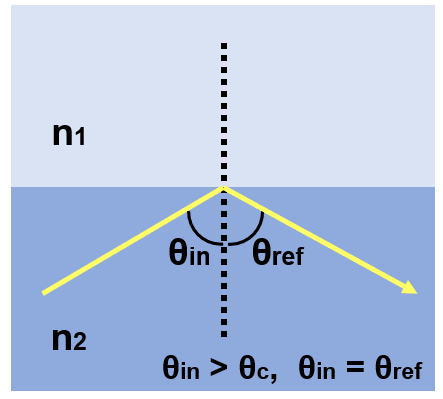

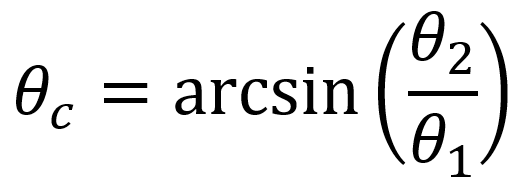

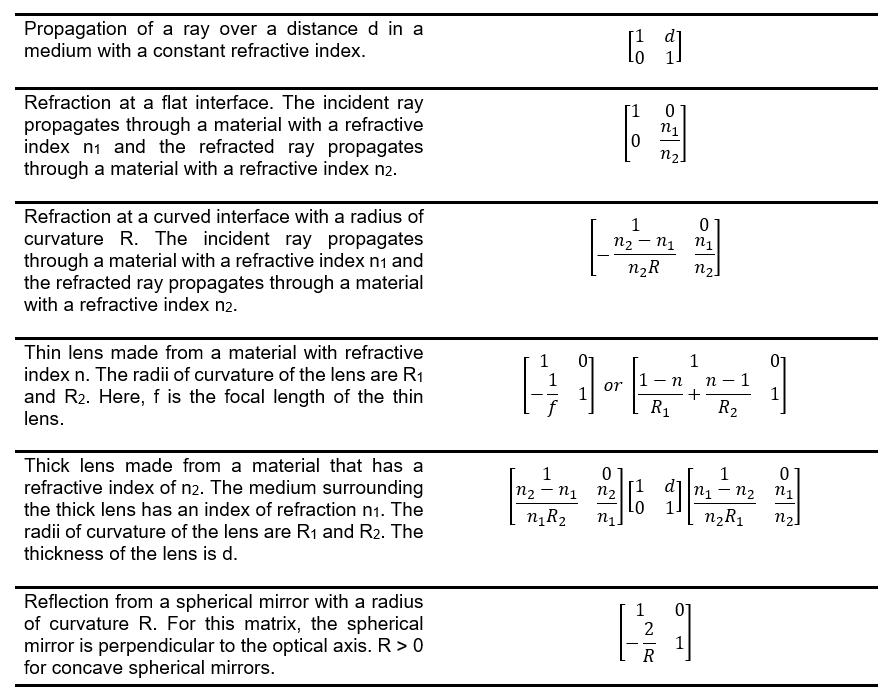

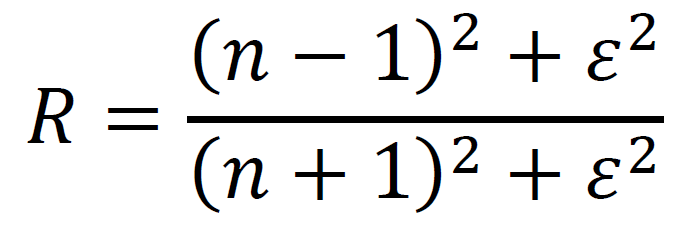

the interface, n1 is the index of refraction of the material i

the interface, n1 is the index of refraction of the material i

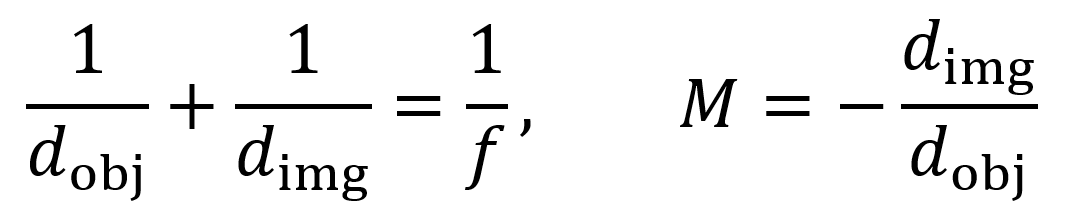

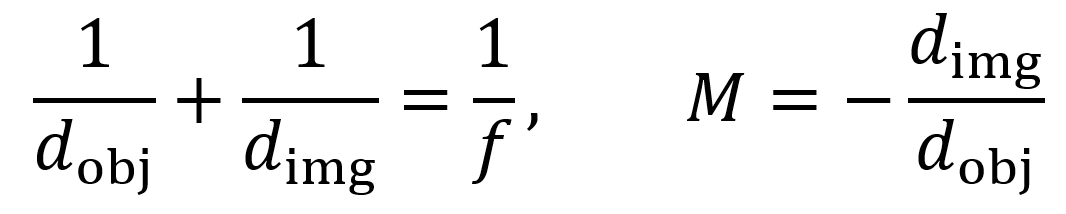

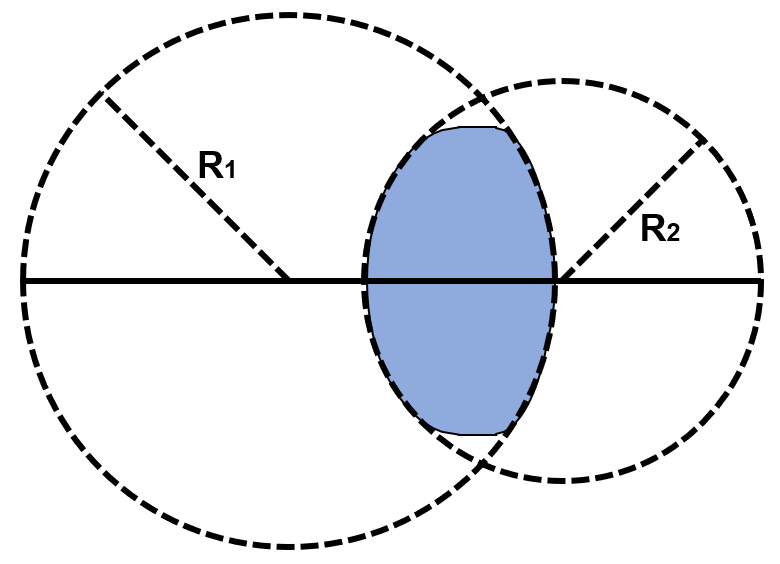

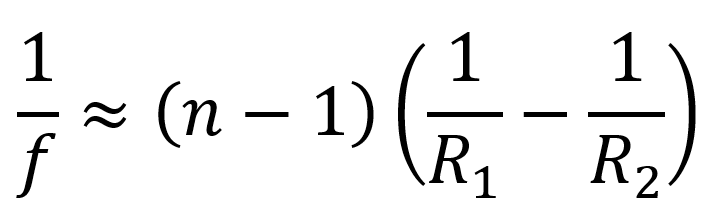

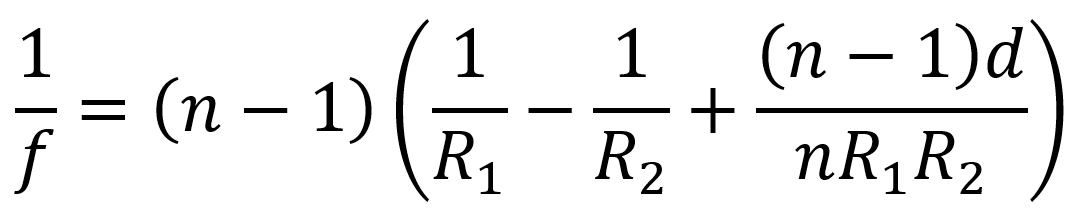

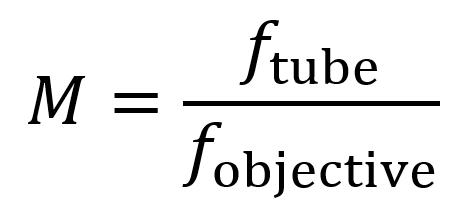

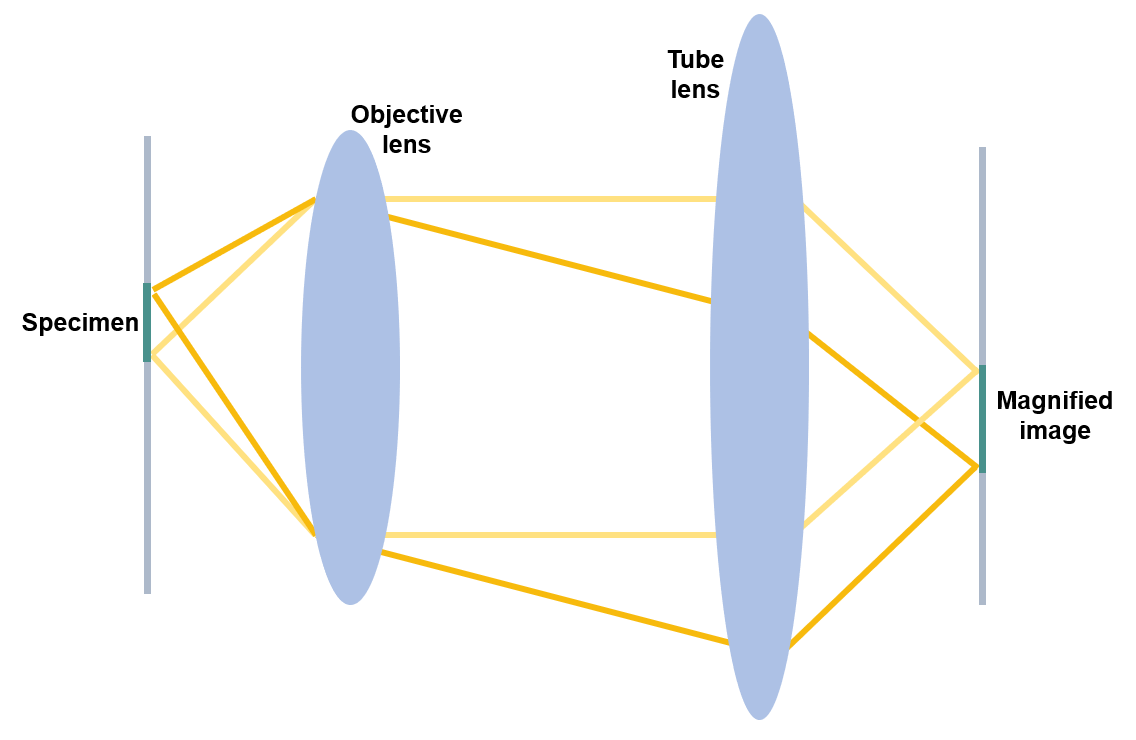

source, R2 is the radius of curvature for the side of the lens furthest from the light source, and n is the refractive index of the material of the lens. Sign conventions for R1 and R2 are usually as follows. If the lens is convex, R1 is positive and R2 is negative. If the lens is concave, R1 is negative and R2 is positive.

source, R2 is the radius of curvature for the side of the lens furthest from the light source, and n is the refractive index of the material of the lens. Sign conventions for R1 and R2 are usually as follows. If the lens is convex, R1 is positive and R2 is negative. If the lens is concave, R1 is negative and R2 is positive.

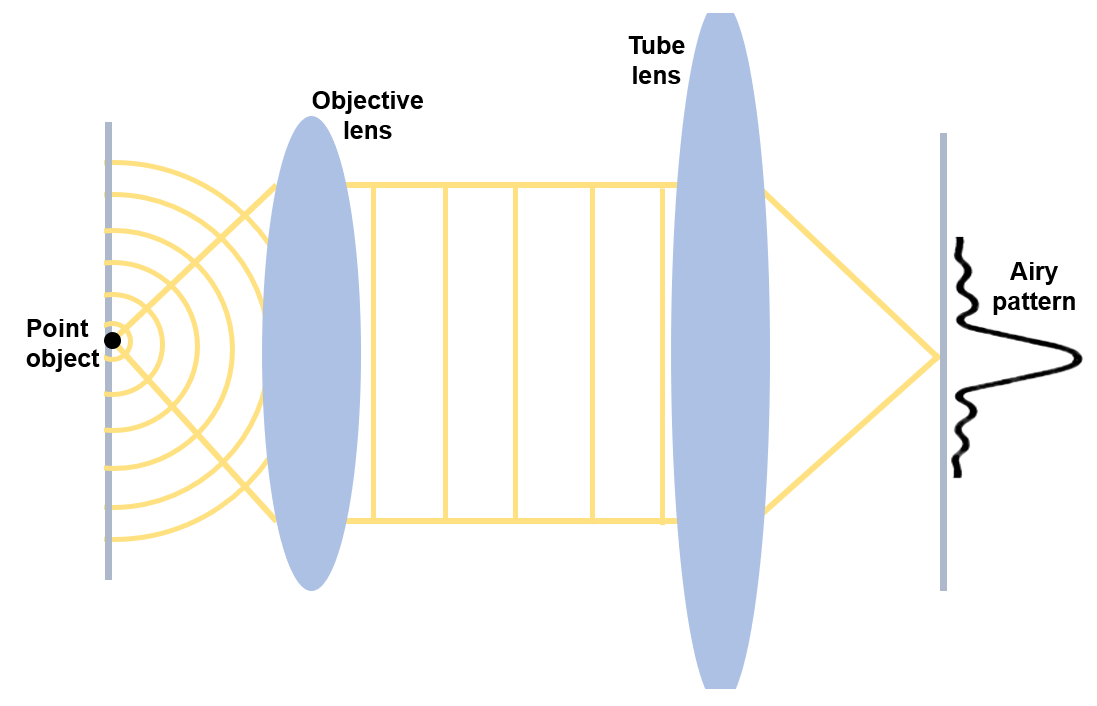

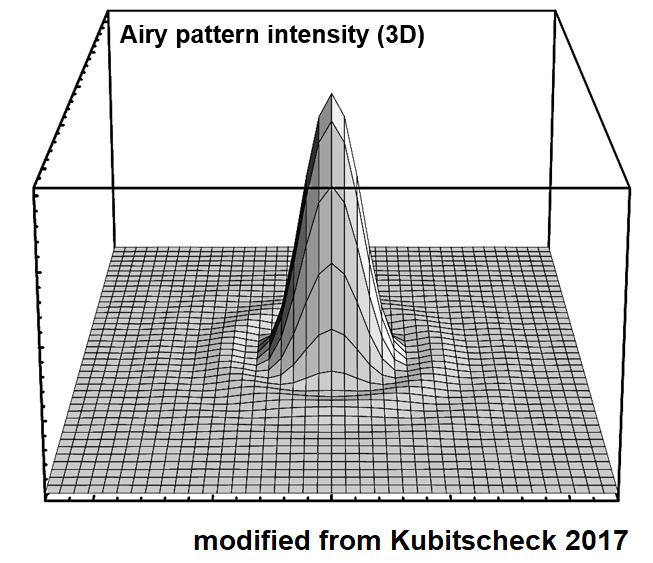

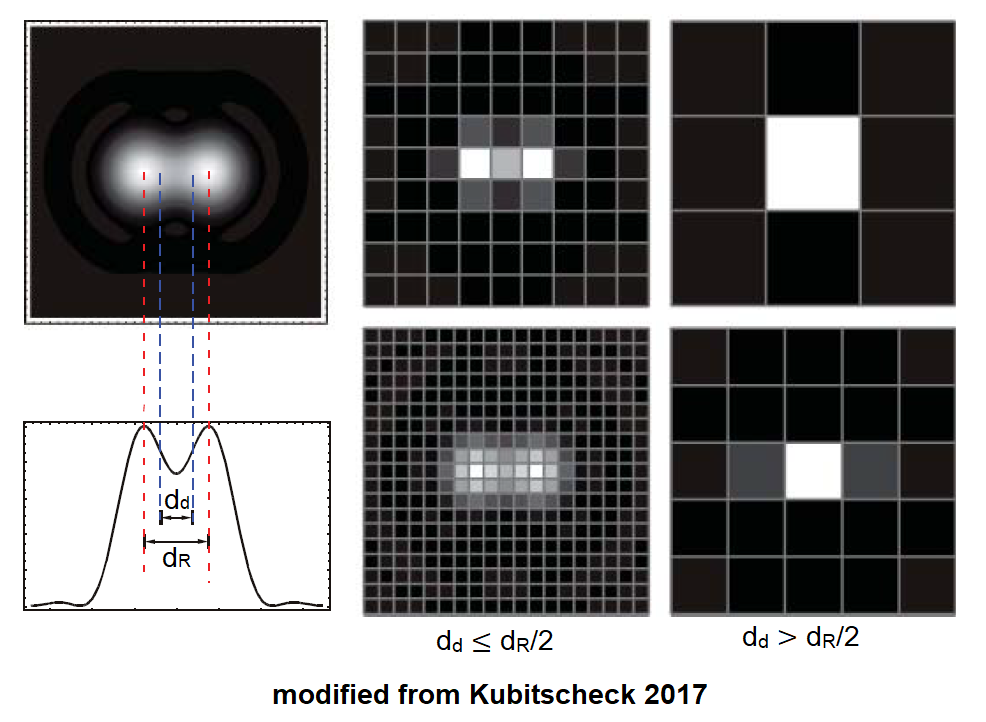

which depends on wavelength and numerical aperture. To understand this, consider diffraction from a point object. (Assume small angles with respect to the optical axis and neglect vector analysis). According to Huygens’s principle, the point object diffracts incoming light into a spherical wave. Part of this spherical wave is converted into a plane wave by the objective lens. Next, the tube lens focuses this light. At the focus on the image plane, the waves constructively interfere since they exhibit the same optical pathlength. But around this point, the optical pathlengths are different and a series of concentric circles of destructive and constructive interference occur. This phenomenon is called the Airy pattern.

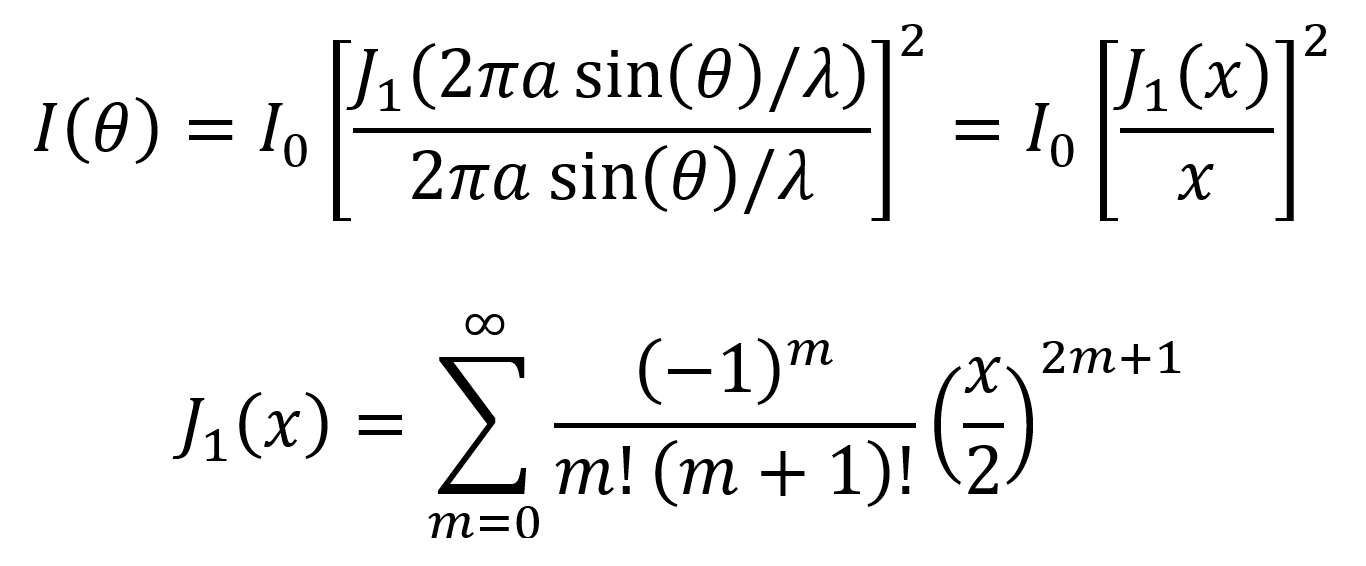

which depends on wavelength and numerical aperture. To understand this, consider diffraction from a point object. (Assume small angles with respect to the optical axis and neglect vector analysis). According to Huygens’s principle, the point object diffracts incoming light into a spherical wave. Part of this spherical wave is converted into a plane wave by the objective lens. Next, the tube lens focuses this light. At the focus on the image plane, the waves constructively interfere since they exhibit the same optical pathlength. But around this point, the optical pathlengths are different and a series of concentric circles of destructive and constructive interference occur. This phenomenon is called the Airy pattern. pattern represents an ideal PSF for a perfect optical system and that many other kinds of PSF exist. By using the Fraunhofer diffraction integral and integrating over a circular aperture (the objective lens) with radius a, the Airy pattern’s field is calculated as a function of the angle θ between the optical axis and the line from the center of the aperture to the observation point (see the figure in the diffraction section for a visual depiction of θ). The function for the Airy pattern’s intensity can be computed by squaring the equation of the field. Here, J1 represents a type of function called a Bessel function of the first kind of order one. I0 is the maximum intensity at the Airy pattern’s center.

pattern represents an ideal PSF for a perfect optical system and that many other kinds of PSF exist. By using the Fraunhofer diffraction integral and integrating over a circular aperture (the objective lens) with radius a, the Airy pattern’s field is calculated as a function of the angle θ between the optical axis and the line from the center of the aperture to the observation point (see the figure in the diffraction section for a visual depiction of θ). The function for the Airy pattern’s intensity can be computed by squaring the equation of the field. Here, J1 represents a type of function called a Bessel function of the first kind of order one. I0 is the maximum intensity at the Airy pattern’s center.

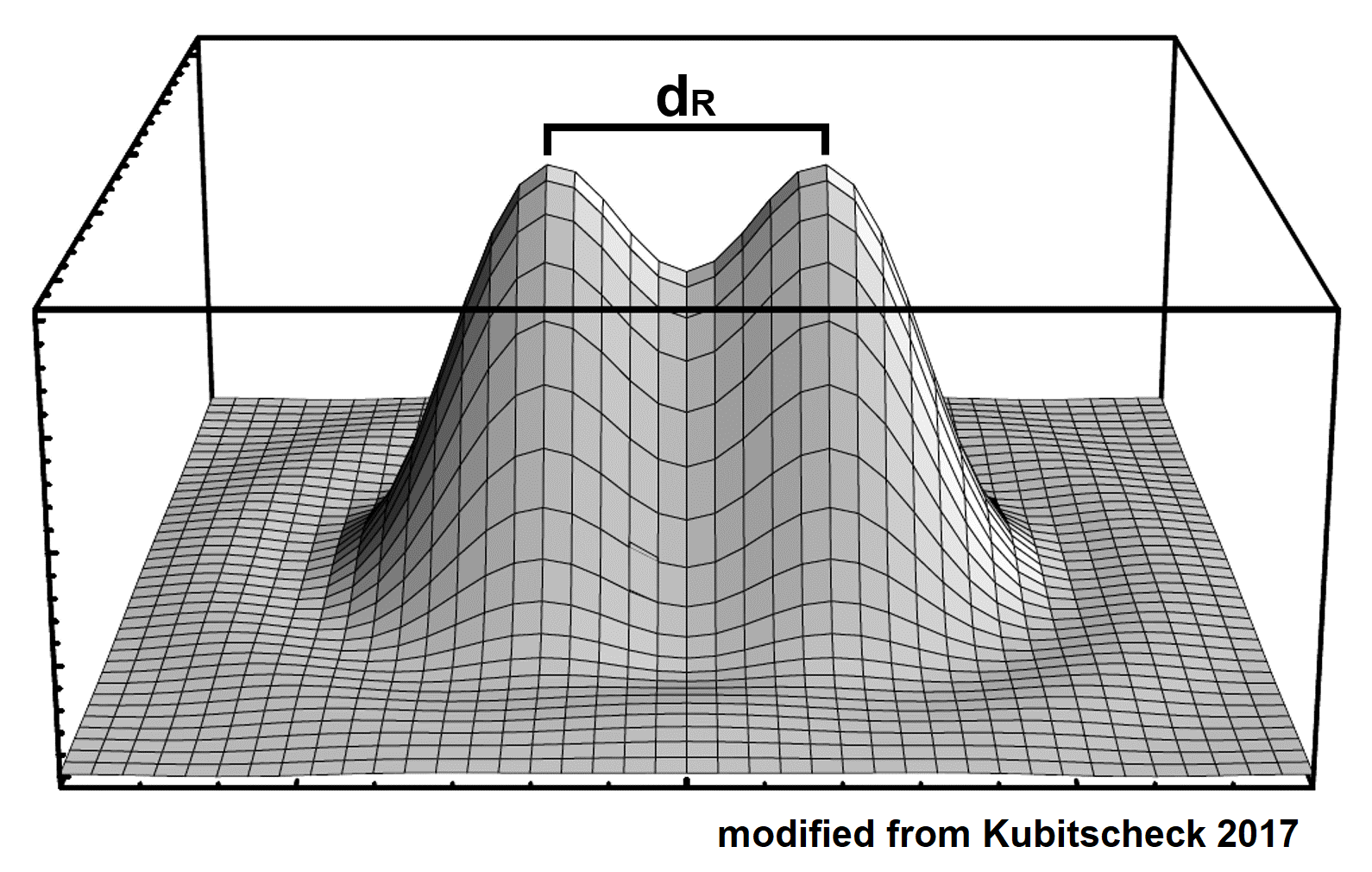

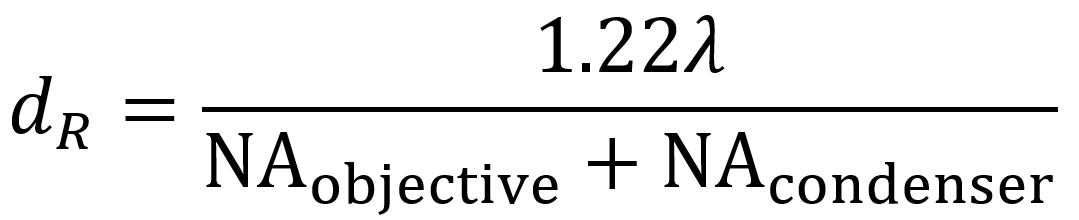

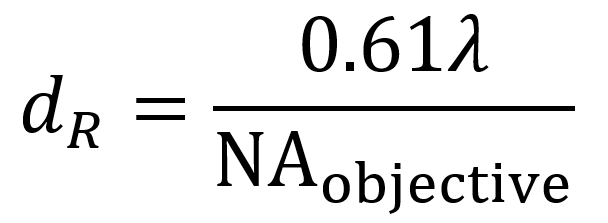

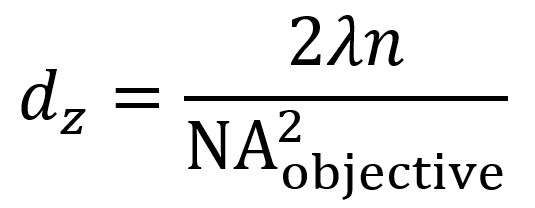

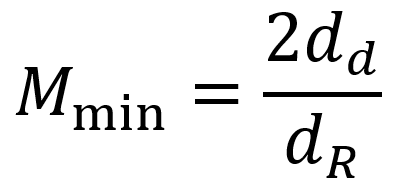

separate objects. This principle is used as a measure of lateral resolution (x and y directions) and is called the Rayleigh criterion. Note that there are also other measures of lateral resolution such as the Sparrow limit.

separate objects. This principle is used as a measure of lateral resolution (x and y directions) and is called the Rayleigh criterion. Note that there are also other measures of lateral resolution such as the Sparrow limit.

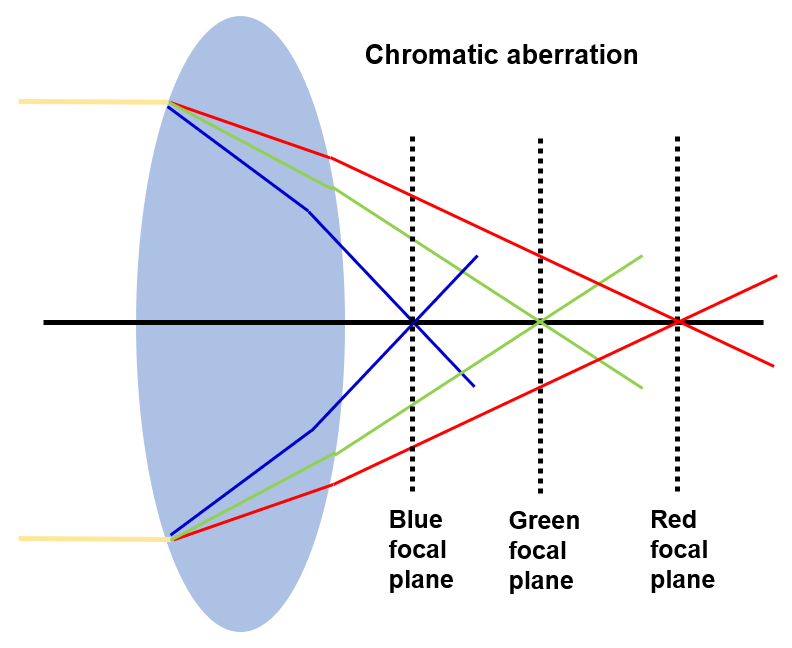

causes lens aberrations that are known as chromatic aberrations.

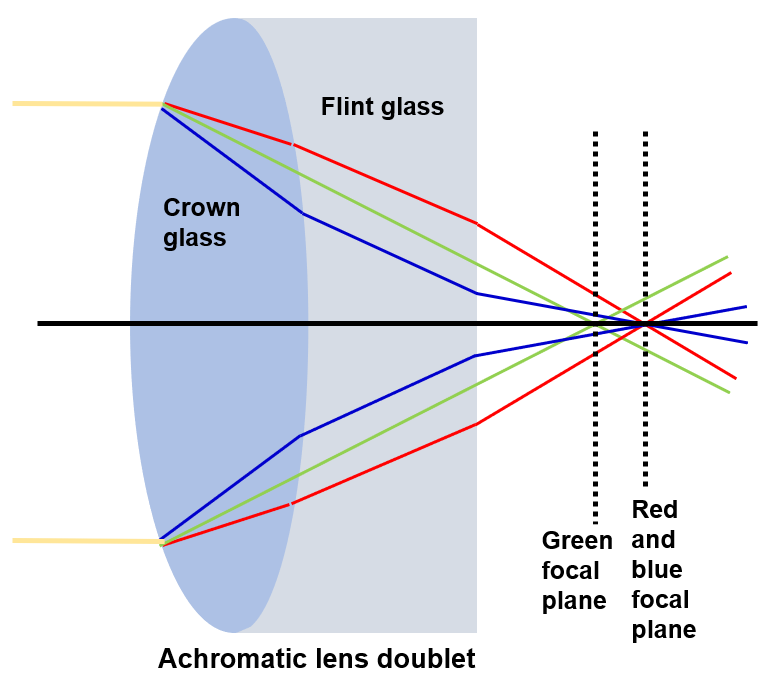

causes lens aberrations that are known as chromatic aberrations. . Dispersion refers to the wavelength dependence of refractive index. Achromatic objective lenses typically employ convex lenses made from crown glass fused to concave lenses made from flint glass, though the entire objective often involves more than just this lens doublet. The differences in dispersion (and therefore refraction) resulting from the crown glass and flint glass cancel each other out, correcting for chromatic aberrations in two wavelengths and creating a single focal plane for both of these wavelengths of light. In addition, achromatic objectives correct for spherical aberrations in a single wavelength which lies between two chromatically corrected wavelengths.

. Dispersion refers to the wavelength dependence of refractive index. Achromatic objective lenses typically employ convex lenses made from crown glass fused to concave lenses made from flint glass, though the entire objective often involves more than just this lens doublet. The differences in dispersion (and therefore refraction) resulting from the crown glass and flint glass cancel each other out, correcting for chromatic aberrations in two wavelengths and creating a single focal plane for both of these wavelengths of light. In addition, achromatic objectives correct for spherical aberrations in a single wavelength which lies between two chromatically corrected wavelengths.

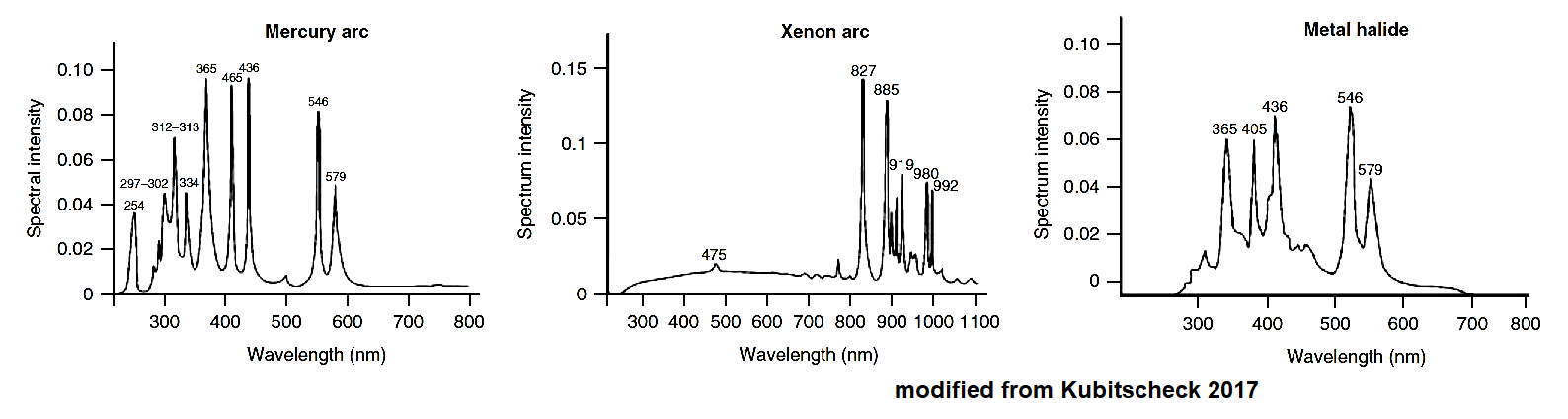

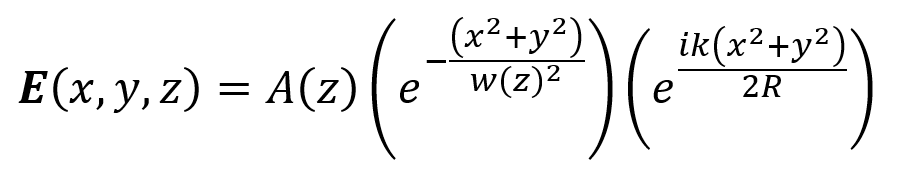

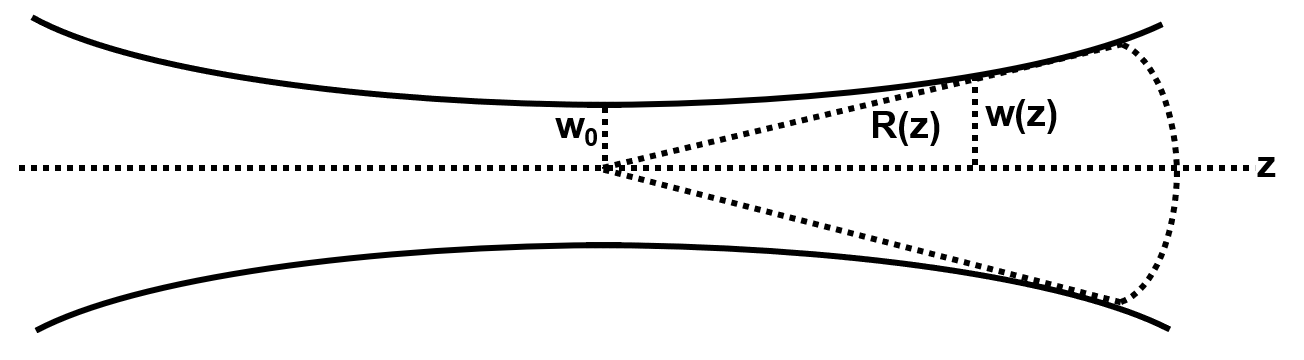

used with laser sources.

used with laser sources.